For all results in this paper, p-values that follow the label r were generated from Pearson’s correlations and p-values that follow standardized betas were generated from t -tests on regressions. All other statistical tests are specified.

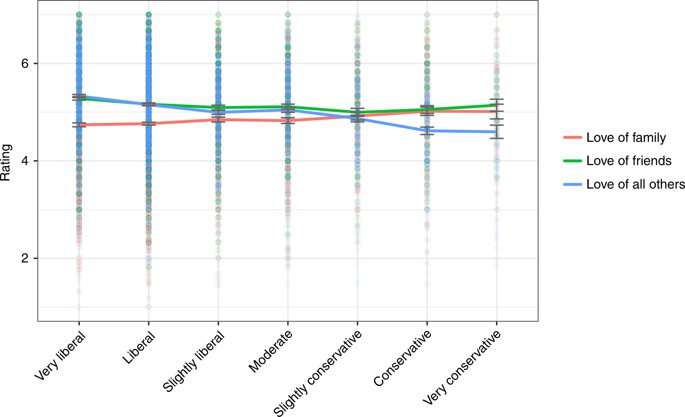

Study 1a tests the hypothesis that liberalism and conservatism would correlate with love for friends and love for family, respectively. The results showed conservatism was positively related to love of family, r (3,362) = 0.065, p < 0.001, and negatively related to love of friends, r (3,360) = −0.065, p < 0.001 (for means, see Fig. 1) (see Supplementary Note 2 for exploration of quadratic effects). Admittedly, these correlations are exceedingly small and should be interpreted with caution. Critically, however, Steiger z -tests conducted on participants who had scores for each of these scales demonstrated that these correlations differed from each other (zs > 2.87, ps < 0.004). In addition, conservatism was unrelated to romantic love (r = −0.01, p = 0.68) (a construct that combines friendship and family relations) and was negatively correlated with love for all others, r (3,362) = −0.20, p < 0.001—this result suggests liberalism is associated with a more universalist sense of compassion.

Fig. 1 Love by political ideology, Study 1a. Error bars represent standard errors, solid lines indicate means. Source data are provided as a Source Data file Full size image

Separate multiple regressions in which romantic love, love of friends, love of family, and love of all others were the outcome variables and political ideology, age, gender, and education were predictor variables revealed that the effect of political ideology remained the same—significant for love of friends, love of family, love of all others, and nonsignificant for romantic love (see Table 1 for standardized betas). These analyses suggest that political ideology meaningfully affects love of friends, family, and others universally, independent of other related demographic variables.

Table 1 Standardized betas for regressions using political ideology, education, age, and gender Full size table

Study 1b tests the hypothesis that just as liberalism and conservatism will correspond to valuing the world and valuing the nation, respectively. Conservative ideology was negatively correlated with universalism, r (13,154) = −0.41, p < 0.001, again demonstrating that conservatism is negatively related to a universal love of others, whereas liberalism is positively related to this sense of universal compassion. In addition, conservative ideology was positively correlated with nationalism, r (13,030) = 0.46, p < 0.001 (see Fig. 2 for means). A Steiger z test on participants who had scores on both of these measures demonstrated that these correlations differed significantly from one another (z = 77.04, p < 0.001).

Fig. 2 Endorsement of values by political ideology, Study 1b. Error bars represent standard errors, solid lines indicate means. Source data are provided as a Source Data file Full size image

Separate multiple regressions in which universalism and nationalism were the outcome variables, respectively and political ideology, age, gender, and education were predictor variables, revealed that the effect of political ideology persisted (see Table 1). Liberalism continued to predict universalism significantly whereas conservatism continued to predict nationalism significantly. These findings suggest that political ideology meaningfully affects universalism and nationalism, independent of other related demographic variables.

Like Study 1b, Study 1c tests the hypothesis that conservatism corresponds to a more parochial or national sense of compassion whereas liberalism corresponds to a universal sense of compassion. Conservatism correlated with identification with country, r (14,176) = 0.28, p < 0.001 a liberalism correlated with identification with the world, r (14,176) = −0.34, p < 0.001. In addition, conservatism showed a small but significant correlation with identification with community, r (14,176) = 0.074, p < 0.001. Steiger z tests demonstrated that the correlations differed significantly for community and country (z = 26.74, p < 0.001), for country and all humans (z = 67.09, p < 0.001), and for community and all humans (z = 43.95, p < 0.001) (for means, see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Identification by political ideology, Study 1c. Error bars represent standard errors, solid lines indicate means. Source data are provided as a Source Data file Full size image

Separate multiple regressions in which identification with community, identification with country, and identification with all humanity were the outcome variables and political ideology, age, gender, and education were predictor variables revealed that the effect of political ideology remained the same (see Table 1). These analyses suggest that political ideology meaningfully affects identification with community, country, and all humans, independent of other related demographic variables.

Studies 1a–1c demonstrate that conservatives are more parochial than liberals—their moral circles are more constrained. This political difference manifests at the level of family versus friends and the nation versus the world. These differences are perhaps unsurprising given well-known policy disagreements on issues affecting these specific circles of family, friends/community, nation, and world16,19,20. If ideological differences in compassion simply reflect policy issue differences, then they should affect attitudes toward targets relevant to these social issues. However, if these ideological differences permeate more deeply into liberals and conservatives general worldviews they should manifest in evaluations of targets completely devoid of social and political relevance. We test this possibility in Studies 2a and 2b.

Study 2a tested whether conservatives (relative to liberals) would prefer tight (relative to loose) geometric structures. We further predicted that these differing preferences would correspond to compassion toward social circles (that involved specifically human targets) examined in Studies 1a–1c. Conservatism was associated significantly with preference for tightness relative to looseness in geometric structures, r (4426) = −0.20, p < 0.001. These results suggest, as predicted, conservatism relative to liberalism corresponds to a preference for tighter structures even when devoid of social relevance.

We also predicted, a priori, that liberals would show a preference for color diversity (i.e., the different colors represented by the geometric structures) across stimuli, but found no significant correlation, r = −0.01, p = 0.35. This finding suggests that ideology specifically relates to preference for the movement patterns of the structures, and not more broadly related to their homogeneity or heterogeneity.

Separate multiple regressions in which preference for looseness-tightness and preference for diversity of color were the outcome variables, respectively, and political ideology, age, gender, and education were predictor variables revealed that political ideology continued to predict looseness-tightness preference significantly. In addition, a multiple regression revealed that preference for diversity was in the predicted direction (associated positively with liberal ideology), but the effect was tiny and only of marginal significance (p = 0.078) (see Table 1). These analyses suggest that political ideology meaningfully affects this basic preference for geometric looseness-tightness, independent of other related demographic variables.

Ideology could be linked to geometric preferences in ways completely unrelated to the link between ideology and social preferences. We therefore examined whether this basic preference for geometric structure maps on to social judgments, testing whether this preference helps account for the relationship between political ideology and moral regard for tight versus loose social structures examined in previous studies.

We tested this by capitalizing on a unique subset of participants who—in addition to completing this study—had also completed one of Studies 1a, 1b, and 1c. These participants enabled us to examine the association between scores on the present geometric shapes task and a social looseness-tightness score reflecting participants’ preference for small social circles (i.e., family and the nation) relative to larger social circles (i.e., friends and the world, respectively).

For each participant, we computed a social looseness–tightness score by first standardizing all measures in Studies 1a–1c, and then averaging scores for explicitly “tight” circles and subtracting this average from the average of scores for explicitly “loose” circles. In other words, we computed the average of standardized scores for the love of family scale (Study 1a), the national security subscale (Study 1b), and the identification with country subscale (Study 1c) (“tight measures”), and computed the average of standardized scores for the love of friends and love for all other subscales (Study 1a), the universalism subscale (Study 1b), and the identification of all humanity subscale (Study 1c) (“loose measures”). We then subtracted the average of loose measures from the average of tight measures as follows:

(average (love for friends Study1a , love for all others Study1a , value of universalism Study1b , identification with all humanity Study1c )) − (average (love of family Study1a , value of national security Study1b , identification with country Study1c )).

To maximize statistical power, we included people who did not have scores for all measures in the equation, although scores were not computed for people who only had scores for the tight or loose side of the equation, leaving 921 participants. In other words, this score reflected participants’ moral regard for friends and global humanity relative to family and one’s nation.

We then used bootstrapping mediation analysis using the SPSS PROCESS macro21 (bias-corrected, 20,000 resamples) to examine whether preference for geometric looseness-tightness mediates the relationship between political ideology and social looseness-tightness. This analysis confirmed partial mediation, in that political ideology indirectly affected people’s preference for social looseness–tightness through a preference for geometric looseness–tightness (95% confidence interval = −0.02 to −0.0002).

Thus, at very least, the relationship between ideology and preference for geometric looseness–tightness is related to preference for social looseness–tightness, and this more “primitive” preference for looseness–tightness might drive people of different political ideologies toward social circles of different expansiveness. Most important, this study demonstrates that the looseness-tightness preference is not limited to circles with which people have preexisting associations, and this perceptual preference is linked to a preference for more well-defined tight versus loose social circles. Study 2b provides a conceptual replication to examine these effects further.

Study 2b is a conceptual replication of Study 2a that again manipulated tightness versus looseness. Conservatism was associated significantly with preference for tightness relative to looseness, r (2072) = −0.15, p < 0.001. These results suggest that again, as predicted, conservatism relative to liberalism corresponds to an overall preference for tighter structures even when these structures are devoid of social relevance.

As we presented geometric structures of different shapes, we had also predicted that conservatives would prefer the shape of a triangle more often than liberals, and liberals would prefer the circle more often than conservatives (because it is the most “egalitarian” shape, with no dot seeming more important than any other). This prediction was confirmed, marginally: conservatives relative to liberals slightly preferred the triangle relative to the circle, r (2072) = −0.04, p = 0.054.

Separate multiple regressions in which preference for looseness-tightness and preference for circle were the outcome variables, respectively, and political ideology, age, gender, and education were predictor variables revealed that political ideology predicted looseness-tightness preference and preference for shape significantly (see Table 1). These analyses again suggest that political ideology meaningfully affects this basic preference for geometric looseness-tightness, independent of other related demographic variables.

Again, to examine the relationship between ideology, geometric looseness–tightness preference, and social looseness–tightness preference, we computed the same social looseness–tightness score as in Study 2a and conducted the same mediation analysis as in Study 2a. This analysis, with 679 participants, also confirmed partial mediation—political ideology indirectly affected people’s preference for social looseness–tightness through a preference for geometric looseness–tightness (95% confidence interval = −0.04 to −0.095). These findings again suggest that the relationship between ideology and geometric looseness–tightness maps on to preferences for social looseness–tightness.

Building on Studies 1–2, showing that liberals and conservatives demonstrate universalism versus parochialism, respectively, Study 3 tests whether this pattern extends to evaluations of nonhumans versus humans, testing the hypothesis that liberals relative to conservatives will show more moral concern toward nonhuman (relative to human) targets. Although existing work shows ideologies associated with conservatism like social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism predict beliefs in human superiority over nonhuman animals and positive attitudes toward animal exploitation22,23, the studies here explicitly test the relationship between political ideology and moral concern toward humans versus nonhumans.

We analyzed separately participants’ ideal and personal allocations of moral regard (measured through “points” described to participants as “moral units”) to different social circles, some of which were clearly human (e.g., family) and some of which were nonhuman (e.g., plants and animals). Political conservatism correlated with actual moral allocation to humans only, r (129) = 0.32, p < 0.001, and ideal moral allocation to humans only, r (129) = 0.26, p = 0.003. Allocation to humans only is directly inversely correlated with allocation to nonhumans, so correlations of the same magnitude emerged in the opposite direction for allocation to nonhumans.

As Fig. 4 shows, the more liberal people were, the more they allocated equally to humans and nonhumans. The further to the right on the ideological spectrum people were, the more likely they were to morally prioritize humans over nonhumans.

Fig. 4 Personal moral allocation to humans and nonhumans by political ideology, Study 3a. Error bars represent standard errors, solid lines indicate means. Source data are provided as a Source Data file Full size image

We also computed a weighted circle score for each participant by multiplying the numerical rank of each category by the allocation to that category and summing these values. That is, we multiplied “immediate family” by 1, “extended family” by 2…“all things in existence” by 16, and summed the values—larger scores indicated larger moral circles. The significant correlation between ideology and this weighted circle score (r (129) = −0.33, p < 0.001; r (129) = −0.24, p = 0.005 for ideal allocation), again demonstrates that as conservatism increases, the extent of the moral circle decreases.

Separate multiple regressions using personal moral allocation to humans, ideal moral allocation to humans, weighted personal circle score, and weighted ideal circle score as outcome variables, with political ideology, age, gender, and education as predictor variables, revealed the same significant effects for political ideology in all cases (see Table 1). These analyses suggest that political ideology meaningfully affects moral allocation independent of related demographic variables.

Finally, we assessed the heatmaps generated by participants’ clicks on the rung they felt best represented the extent of their moral circle. These qualitative results also demonstrated that liberals (individuals who selected 1, 2, or 3 on the ideology measure) selected more outer rungs, whereas conservatives (individuals who selected 5, 6, or 7 on the ideology measure) selected more inner rungs (see Fig. 5). Overall, these results suggest conservatives’ moral circles are more likely to encompass human beings, but not other animals or lifeforms whereas liberals’ moral circles are more likely to include nonhumans (even aliens and rocks) as well. Study 3a revealed these patterns also when asking about participants’ ideal moral circles. This suggests that both liberals and conservatives, although differing in their moral allocations, feel that their pattern of allocation is the ideal way to adjudicate moral concern in the world.

Fig. 5 Heatmaps indicating highest moral allocation by ideology, Study 3a. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Note. The highest value on the heatmap scale is 20 units for liberals, and 12 units for conservatives. Moral circle rings, from inner to outer, are described as follows: (1) all of your immediate family, (2) all of your extended family, (3) all of your closest friends, (4) all of your friends (including distant ones), (5) all of your acquaintances, (6) all people you have ever met, (7) all people in your country, (8) all people on your continent, (9) all people on all continents, (10) all mammals, (11) all amphibians, reptiles, mammals, fish, and birds, (12) all animals on earth including paramecia and amoebae, (13) all animals in the universe, including alien lifeforms, (14) all living things in the universe including plants and trees, (15) all natural things in the universe including inert entities such as rocks, (16) all things in existence Full size image

One caveat to Study 3a is that we constrained the number of units that participants could assign to each group, forcing participants to distribute moral concern in a zero-sum fashion (i.e., the more concern they allocate to one circle, the less they can allocate to another circle). Although research suggests that people indeed do distribute empathy and moral concern in a zero-sum fashion24,25,26, this feature of Study 3a imposes an artificial constraint. Therefore, to examine whether a similar pattern would emerge without this constraint, we conducted Study 3b to test whether the effect would replicate using unlimited units.

Study 3b is a conceptual replication of Study 3a, allowing participants unlimited moral units to distribute to various circles. Conservatism was positively correlated with the human allocation proportion score only, r (261) = 0.14, p = 0.025, and hence negatively with the nonhuman allocation proportion score (for means, see Fig. 6). A multiple regression using the human allocation proportion score as an outcome variable with political ideology, age, gender, and education as predictor variables revealed the same significant effect for political ideology (see Table 1). Thus, even when participants’ allocations were not constrained, the same pattern replicated such that liberals distribute empathy toward broader circles and conservatives distribute empathy toward smaller circles.

Fig. 6 Proportion of moral allocation by ideology, Study 3b. Error bars represent standard errors, solid lines indicate means. Source data are provided as a Source Data file Full size image

Importantly, in addition to examining proportion, we also examined total allocation, and allocation to humans and to nonhumans. Liberals and conservatives did not differ such that political ideology was not significantly correlated with total allocation to all targets, r (261) = 0.04, p = 0.51, total allocation to humans, r (261) = 0.04, p = 0.50, or total allocation to nonhumans, r (261) = 0.04, p = 0.51 (this pattern of the results was the same when excluding the one participant whose allocations fell outside of 3SD of the mean; see below). Separate multiple regressions using these total allocation scores as outcome variables with political ideology, age, gender, and education as predictor variables revealed the same nonsignificant effects for political ideology (see Table 1). Again, these findings demonstrate that liberals and conservatives differ not in the total amount of moral regard per se but rather they differ in their patterns of how they distribute their moral regard.

Formally_Nightman on October 2nd, 2019 at 02:04 UTC »

How are they defining morality and then measuring concern?

Bubrigard on October 2nd, 2019 at 00:59 UTC »

What I find interesting is that the differences in the mean are really not that far apart (looking at the central lines).

All hover around 5. So, while they are different, they aren't too far off each other.

oodlesof2dles on October 1st, 2019 at 21:05 UTC »

If you're like me and had to re-read the title a few times over, it's saying:

Liberals express greater moral concern towards friends and the world Conservatives express greater moral concern towards family and the nation