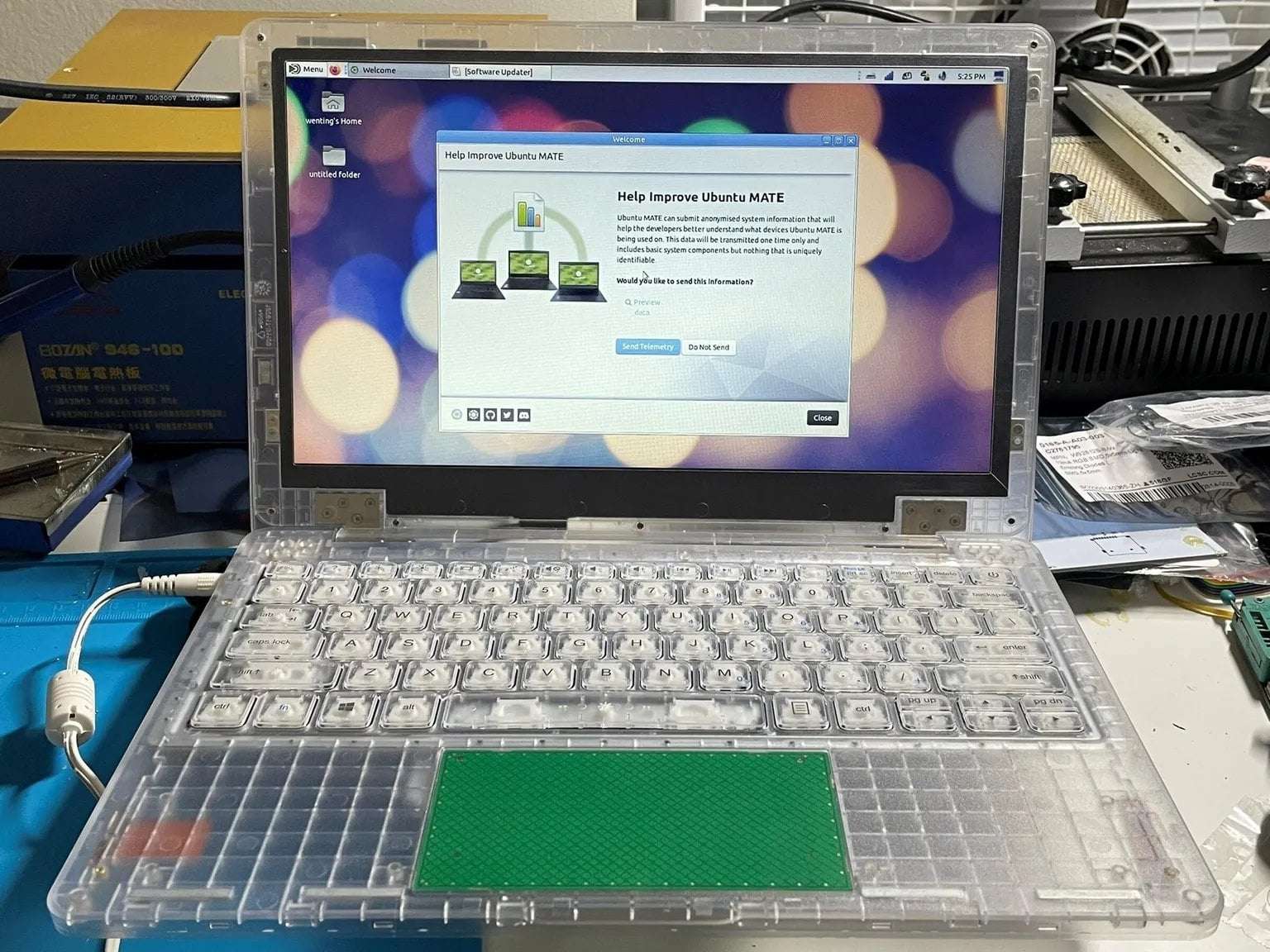

When Wenting Zhang bought a clear plastic laptop on eBay, he had no idea about the chain of events he would kick off. The device turned out to be a secure computer used for jail and prison education, and he was initially unable to get past a black login screen.

That’s because the laptop was working the way it was supposed to. Many typical features, such as a USB port, were missing because the device is designed to restrict users’ ability to communicate with the outside world.

Zhang, an electrical engineer in Boston, decided to post about trying to unlock his Justice Tech Solutions Securebook 5 on the social platform X. The thread went viral — also catching the attention of Washington corrections officials, who have used the device for college programming since 2020.

Of particular concern was an article about Zhang’s thread published on a hacker website that shared the default password for the underlying software that starts the laptop’s operating system, presenting what the Department of Corrections considered a security concern.

The department then announced Thursday, five days after Zhang’s viral post, that it would collect all secure laptops from incarcerated students statewide “to provide an immediate system update.” By Saturday, corrections staff had collected around 1,200 laptops, spokesperson Chris Wright said in an email.

Wright confirmed no one incarcerated in Washington prisons had attempted to unlock their devices but said the decision was “made out of an abundance of caution.” It wasn’t immediately clear whether other states whose corrections departments use Securebook 5 laptops have also pulled the devices.

“DOC recognizes how crucial educational programming is and we do everything we can to avoid disruption to classes,” Wright said in an email.

Students said they were given little information about when and if the devices would be returned, and many wondered if they’d lose access to the work saved on the laptops, which need to be placed into a dock to upload or download information. Students enrolled in community colleges also expressed concern that they lost access to their devices immediately before winter quarter finals.

Steven Pawlak, who’s incarcerated at Washington Corrections Center in Shelton, said the laptop issued to him in January at the beginning of his first college course has been a huge help. While he meets with his Centralia College instructor and fellow students twice a week, he works exclusively on the laptop, as the teacher has all the students doing math problems using Excel spreadsheets rather than by hand. “We already have computers,” he said his instructor told him. “You don’t need to be one.”

After his laptop was collected last week, Pawlak is frustrated because he doesn’t know when he’ll get it back. “If this is how my first class goes, I have no idea what the rest will be like,” he said.

Students enrolled in the bachelor’s program through the University of Puget Sound, in collaboration with the Freedom Education Project Puget Sound (FEPPS), were particularly frustrated because they’re in the final semester of their program.

“This is a critical moment because students in our BA program are preparing to graduate and finish research and writing for their capstone projects,” said Tanya Erzen, faculty director and former executive director of FEPPS. “It’s already a struggle to conduct research without access to the internet or databases, and this will only exacerbate the situation.”

Several women at Gig Harbor’s Washington Correctional Center for Women reported that they were placed on lockdown Friday while correctional officers came to collect the laptops.

They were told the laptops needed an update, but “they wouldn’t come in like it was a raid for a simple systems update,” said Lisa Kanamu, one of the prospective FEPPS graduates.

She’s not looking forward to the possibility of having the hand write her papers again. “Can you imagine writing a 12-page paper and needing to make significant changes on page two? You have to rewrite the entire paper,” she said.

Other students in a community college coding and web design program said they were informed web development classes were canceled until further notice.

Wright said the department was concerned students could use the default administrative password to reset the laptops and “remove the security framework,” allowing them to install new operating systems and “override all security protocols.”

Securebooks, like most prison tech, are programmed to only boot up from the operating system that’s installed on them, said Jessica Hicklin, the chief technology officer at Unlocked Labs, a St. Louis education tech nonprofit that uses Securebooks and other Justice Tech hardware.

That operating system is set up so the user can only access certain programs and files. “Most corrections departments are nervous about incarcerated users having full access to administrative functions of the operating system,” she said.

Hicklin, who’s formerly incarcerated, said the Washington officials’ decision to pull the laptops was unnecessary given the limited amount of potential for actual harm. “As long as the network is properly secured, then there is no real credible security threat,” Hicklin said.

But former corrections officials from Washington and other states found the decision reasonable, given the possible security concerns.

The man who made the devices said there’s little someone inside could actually do with a hacked Securebook. They’d need to fashion a USB port, be able to install another operating system, and get access to a docking station, said Jeremy Schwartz, Justice Tech president. Even when the devices are docked, they’re not connected to the wider internet.

“A lot of states actually felt very good when they got into the technical details of the levels of security that were there,” he said, noting that the work of outside hackers couldn’t be replicated in a prison environment. “That’s why it went viral.”

So how does a prison laptop end up on eBay?

The laptop that Zhang bought came from a state whose corrections department contracts with a Milwaukee-based nonprofit to dispose of its old laptops. But instead of recycling the devices, the organization resold them, selling out of 100 Securebooks after Zhang’s post went viral.

It’s not uncommon to find personal tablets from prison tech companies on reseller sites. In some places, incarcerated people pay for their own music and communication devices and are allowed to take them when they’re released.

But it’s much more unusual for secure laptops to find their way to the internet marketplace. Justice Tech only sells devices directly to colleges, correctional agencies and other organizations that work with incarcerated learners, not to individuals, Schwartz said.

Stacy Burnett, who oversees a program at research organization ITHAKA that allows incarcerated people to access research materials, said many prison officials have done the best they can in building technology infrastructure, but security concerns sometimes require them to shut everything down.

“In those instances,” she said, “the only line of defense is to confiscate student devices until the problem is diagnosed, isolated, and resolved.”

“It can take months, and creates considerable disruption for the students and the colleges or vocational program providers.”

Washington corrections officials said they’re working to minimize disruptions for incarcerated learners by expediting delivery of new Securebooks in the next few weeks, backing up student work and increasing lab time on desktop computers. The department also expects students from the women’s prison bachelor’s program to be able to earn their degrees on time.

Tomas Keen, a writer incarcerated at Washington Corrections Center in Shelton, contributed reporting. This story was co-published by The Seattle Times.