When Gretchen Whitmer first emerged as the likely Democratic candidate for governor of Michigan, in late 2017, the mayor of Detroit, Mike Duggan, circulated a memo urging labor unions and Democrats to find a better-known figure to lead the ticket. Duggan wanted Senator Gary Peters to run; the United Auto Workers preferred Representative Dan Kildee. But neither member of Congress wanted anything to do with Lansing. Mark Bernstein, a politically connected Ann Arbor personal-injury lawyer, recalled that, while watching a University of Michigan basketball game at Duggan’s house, the Mayor tried to persuade him to get in the race. By the end of the primary, Whitmer had outlasted the established alternatives, and went to Detroit to meet with the leaders of the U.A.W. (“Big talkers,” a Whitmer insider called them.) The word was that the union and its allies were prepared to spend two million dollars on the election. “Let’s ask them for $3.5 million,” Whitmer told her campaign staff. “They’re the last ones on board—what can they say?” At the meeting, according to an aide, the U.A.W. pledged to give her the whole bundle.

Lansing, like many state capitals, offers a politician real power without much prospect of fame. In small office buildings and well-worn restaurants, lobbyists and legislators shape and reshape the fate of the auto industry and, with it, much of the Midwest. Whitmer, who is fifty-one, has worked in the capital for nearly her entire adult life. She knows just about everyone in town and is married to a local dentist. (“Everyone loves him,” a Republican lobbyist told me. “He’s very funny.”) Mark Burton, who was Whitmer’s principal aide for more than a decade, said, “The Governor gives off a vibe. She’s super relatable, and super likable, but also a little intimidating.”

Burton recalled an episode from December, 2011, when Whitmer was the minority leader in the state senate, and getting just about anything done depended on her relationship with the Republican majority leader, Randy Richardville. Whitmer had spent years working on an anti-bullying law with the family of a fourteen-year-old boy in her district who had killed himself after an eighth-grade-graduation hazing ritual. The measure was set to pass, but, at the last moment, the Republicans, under pressure from the Catholic Church, added a clause exempting bullies who claimed a religious justification. Whitmer, as Burton told it, “said, essentially, this is bullshit.” The following week, Whitmer appeared on the floor of the Senate, accompanied by a cartoon of Richardville holding a driver’s license. Above the majority leader’s face, it read “License to Bully.” Stephen Colbert eventually picked up the story. The Republicans backed down.

Stunts like this might not have made it past Grand Rapids, except that Michigan appeared to be swinging radically to the right. In 2016, Donald Trump won the state, promising to bring back auto-industry jobs and denouncing free trade and faraway élites. His victory seemed to place Michigan at the center of a global turn toward populism and racist resentment. Whitmer had a different interpretation. “2016 was just a low voter turnout,” she told me. “People were just, like, ‘Government doesn’t work.’ They were cynical and mad and wanting to tune out.” It wasn’t that the industrial Midwest had fallen in love with Trump, in her view. It was that people didn’t care enough to vote against him. Still, when a policy expert who briefed Whitmer at her home during the 2018 gubernatorial campaign asked why she was running, she replied, “Because I’m the only one who can do it.” That fall, she won handily.

During the pandemic, Trump attacked her for imposing long school and business closures. She endured an armed mob at the state capitol and a plot by a group linked to a right-wing militia to kidnap and kill her. Last November, Whitmer tied her candidacy to a state constitutional amendment guaranteeing the right to abortion and won reëlection by ten points, sweeping the suburbs so convincingly that the Democrats gained control of both houses of the Michigan legislature for the first time in forty years.

Since then, Whitmer’s Democratic majority has allocated more than a billion dollars to support the auto industry’s green transition; quintupled a tax credit for poor families; repealed a law that made Michigan a right-to-work state; and enacted new protections for L.G.B.T.Q. people. After a forty-three-year-old local man went on a shooting spree at Michigan State University, in February, killing three students, some modest, if hard-won, gun-control measures were put in place. “I don’t know that we’ve ever watched the legislature go as quickly as they have,” Maggie Pallone, a public-policy analyst in Lansing, said earlier this year, in an article in the Detroit News. Similar breakthroughs have come in Minnesota and Pennsylvania. What’s happening in the Midwest, one of Whitmer’s advisers told me, is a “Tea Party in reverse.”

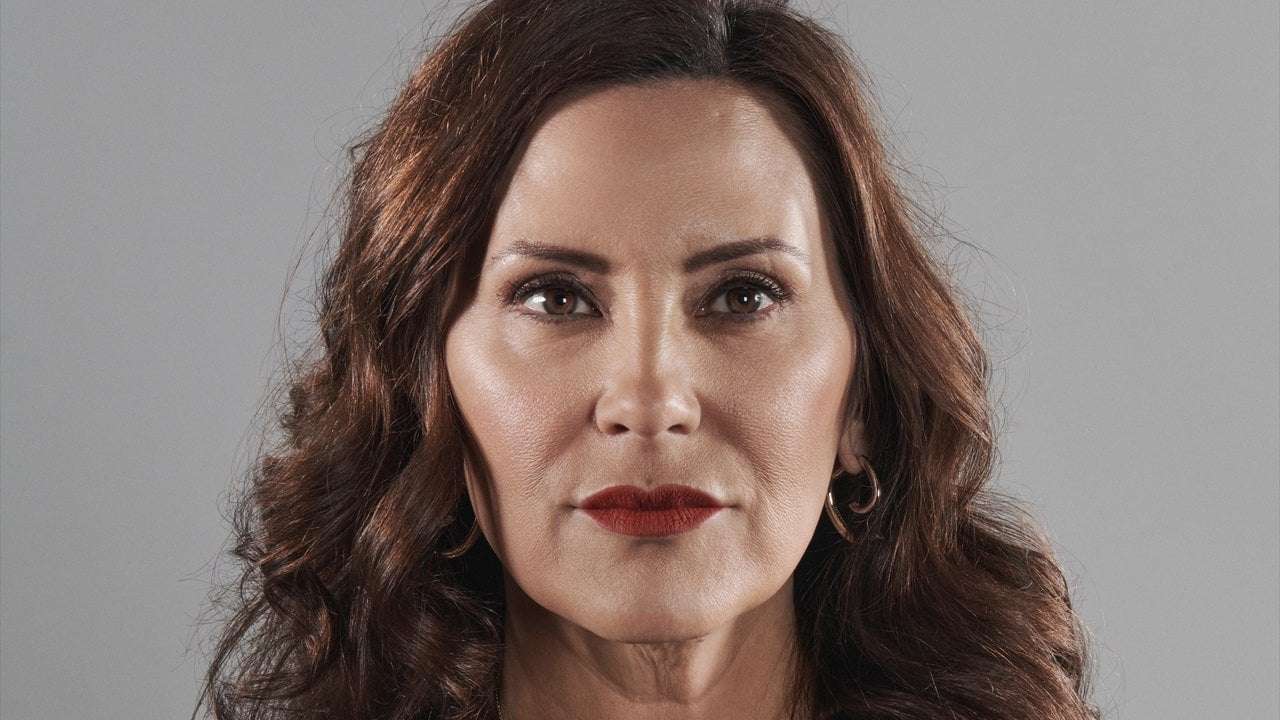

Whitmer’s first ambition was to be an ESPN anchor, and she still has a sportscaster’s instinct to inhabit a highly formal setting and then destabilize it with informality. She speaks briskly, avoids jargon, and runs ahead of schedule. David Axelrod, Barack Obama’s senior adviser, who owns a house in Michigan, told me, “She’s plainly smart, she’s very agile. But there is a sense in which ‘I might know a person like this.’ ” One afternoon in May, I watched Whitmer record a series of TikTok videos in her “ceremonial office,” used for bill signings and photo shoots, which was decorated with portraits of past Michigan governors, many of them sporting muttonchops. Whitmer has wavy chestnut hair and a prominent chin that she dropped like a gavel at the start of each take. When she recorded a video wishing happy anniversary to the Ford Motor Company, a man in the room mentioned that his first car was a Ford Focus, which had been impounded for unpaid parking tickets. “I know so many young men who had their car impounded for parking tickets,” Whitmer said. “Sorry if that sounds sexist. I don’t know as many women.”

At the height of the pandemic, the Detroit rapper Gmac Cash recorded an anthem titled “Big Gretch”: “Throw the Buffs on her face ’cause that’s Big Gretch / We ain’t even ’bout to stress ’cause we got Big Gretch.” Whitmer has expressed ambivalence about the nickname (“Certainly, no woman I know likes to be called big”), but it has come to capture what her supporters admire most about her: she is a Democrat who fights and wins in one of the most competitive parts of the country. “People think she’s an intellectual, but she’s not,” Tommy Stallworth III, a veteran Detroit pol who is now a Whitmer senior adviser, said. “She is a wartime consigliere.”

More broadly, Whitmer’s wins suggest a different story of the Midwestern heartland, one dominated not by a political backlash in declining industrial cities but by a moderate liberalism in prosperous suburbs, where the Democrats have, for now, found the majorities and the money to stave off Trumpism. “Even I had my doubts over the last few years,” Whitmer told me. “What is it going to be by the time I’m up for reëlection?” When I asked her what it has taken to be a successful politician during this period, she said, “It’s an interesting combination of cold blood and genuine passion.”

For most of the second half of the twentieth century, Michigan’s politics were governed by a certain equilibrium. Long-tenured pro-union Democratic congressmen dominated in Washington. In Lansing, pro-business Republicans were the norm, personified by Mitt Romney’s father, George, who turned a successful career as an auto executive into a stint as Michigan’s governor, in the sixties. Whitmer came from a bipartisan political family. Her mother, Sherry, was a lawyer who would eventually work under the state’s Democratic attorney general (and future governor) Jennifer Granholm, and her father, Dick, had served in the cabinet of Romney’s Republican successor, William Milliken. In Whitmer’s baby book, there is a press release: “Commerce Director and his wife have a baby, Gretchen Whitmer.”

Whitmer’s parents divorced when she was six years old, and she and her two younger siblings were raised mostly in the suburbs of Grand Rapids by their mother. Dick, based a couple of hours away, in Detroit, became the C.E.O. of Michigan Blue Cross Blue Shield. The family stayed relatively close. “My mom’s mom used to call my dad the world’s finest ex-husband,” Whitmer’s sister, Liz Whitmer Gereghty, told me. A lifelong friend of Whitmer’s compared their upbringing to the teen-age raunch-com “American Pie,” which was set nearby. “Everyone going out to Lake Michigan after the prom—it all felt very familiar,” the friend said, then quickly added, “Far better behaved than that.” (Whitmer offered a similar characterization: “My parents would tell you I was having way too much fun and should have had a lot more focus.”)

“Now that I’ve given up on dating, I have enough time and money to date again.” Cartoon by Carolita Johnson Copy link to cartoon Copy link to cartoon Shop Shop

Politics was not her main interest. “I played sports,” she said. “But, more than that, I was kind of a rabid fan.” She was working in the football office at M.S.U. when her father, then a prominent power broker, encouraged her to get an internship in the office of the Democratic leader in the Michigan House, whose chief of staff, Daniel J. Loepp, later became C.E.O. of Michigan Blue Cross Blue Shield. “She was like a sponge,” Loepp told me recently. “I always knew she would eventually run for office.” When a House seat opened up in East Lansing ahead of the 2000 election, Loepp urged Whitmer to run and helped her get the endorsement of a popular former state attorney general. She won by two hundred and eighty-one votes; it was her last truly close race. She was twenty-nine years old. “It’s not that Gretchen Whitmer came out of the womb and said she was going to be governor of Michigan,” Whitmer told me. “Every jump in my career, I’ve had that moment where I looked around and thought, Well, look who’s out there. I could probably do a better job.”

CFB_Mods_Eat_Poop on July 18th, 2023 at 12:11 UTC »

She has been doing a really good job so far despite having some initial odds stacked against her. There are undeniable improvements being made (mainly to roads and infrastructure) that are just objectively difficult to argue against as net positives. Which you can see from the verbal garbage the MI gop is failing to have land.

Additionally, the MI gop is so fucked from jumping on the trump train they have essentially bankrupted themselves across the state in quite spectacular fashion. And the gop crown jewel of Ottawa county got taken over by crazies and the people on both sides there are not amused. Love to see it.

Looking good for the future in Michigan, but there’s still a lot of fighting to do to fix decades of dumb dumb Republican policies.

MiracleMan1989 on July 18th, 2023 at 12:03 UTC »

She also ran on fixing the roads and is delivering. There’s so much current road work it’s absurd. Inconvenient right now, sure, but good short term jobs and it will pay off soon!

wild_man_wizard on July 18th, 2023 at 11:16 UTC »

Imagine, wooing progressive voters by implementing progressive policies!

How novel! I hope the DNC considers this implementing this revolutionary concept nationwide.