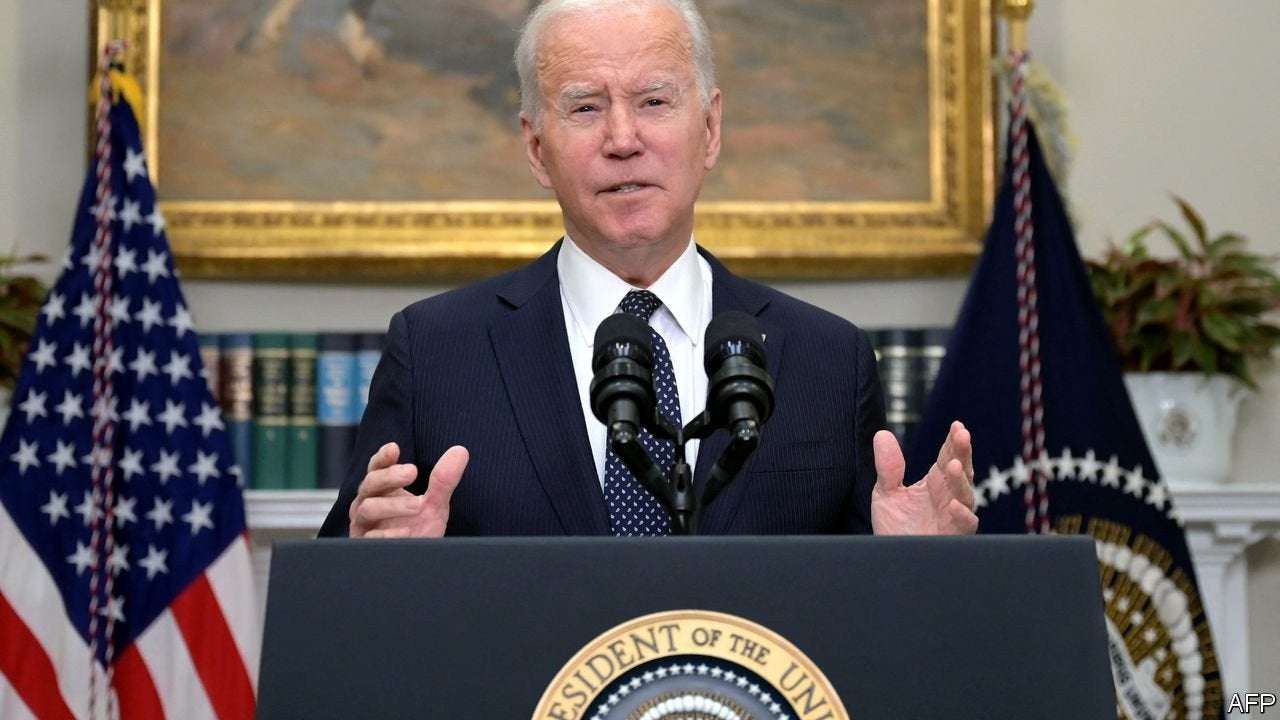

FOR SEVERAL weeks, even as they raised the alarm about Russia’s unprecedented military build-up on Ukraine’s border, Western leaders and officials emphasised that Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, had not yet made a final decision. There was still time, they said, for Mr Putin to step back from the brink. On February 18th the tone changed. Joe Biden, America’s president, said that he was “convinced”, based on intelligence, that Mr Putin’s mind was now made up. Russia would attack Ukraine “in the coming days”—and it would target Kyiv, the capital.

The crisis on Ukraine’s border has simmered since October, when American officials first noticed unusual military movements that prompted them to warn, the next month, of an invasion. Now it may have come to a head. For weeks, America and its European allies have warned that Russia would seek to manufacture a pretext for war, such as a “false flag” attack which would be blamed on Ukraine. In recent days, evidence that such pretexts are being constructed has been coming thick and fast.

On February 15th Mr Putin claimed, without the slightest evidence, that Ukraine’s government was perpetrating “genocide” in the Donbas, a region of south-eastern Ukraine where Russia has armed and backed proxy militias, and their self-declared “republics” in Donetsk and Luhansk. On February 18th those statelets began evacuating citizens to Russia, as the Kremlin claimed, again without evidence, that Ukraine was preparing to invade the Donbas. That evening, Russia’s state-run media circulated photos and videos of an explosion outside a government building in Donetsk and the sabotage of a gas pipeline near Luhansk. A day later both the Donetsk and Luhansk republics announced a general mobilisation for war. In Luhansk, men aged 18 to 55 were told they would not be allowed to leave. Russian media claimed that a Ukrainian shell had landed inside Russia itself.

This apparently spontaneous spiral was as much theatre as crisis. The idea that Ukraine’s army, having observed exemplary restraint for months, would launch an attack while surrounded by as many as 190,000 hostile troops is fanciful. Researchers studying the videos in which the Donetsk and Luhansk leaders announced their evacuations found that the messages had, in fact, been recorded on February 16th, two days earlier, and before the escalation in shelling had begun.

On February 14th Sergei Shoigu, Russia’s defence minister, told Mr Putin that the country’s “exercises”—the Kremlin’s term for the build-up—were “coming to an end” and that units would be withdrawn to barracks. Instead, in the days that followed, more forces arrived. Russia now has 110 to 125 battalion tactical groups (BTGs)—fighting formations of 1,000 or so troops equipped with artillery, air defence and logistics—deployed on the border, according to British and American defence officials.

New satellite imagery published on February 18th shows large numbers of newly-arrived aircraft in Lida, in Belarus; Millerovo, a Russian air field 16km from the Ukrainian border (see below); and Valuyki, 27km from the border. Armoured vehicles belonging to Russia’s VDV airborne forces, and rigged with parachutes, have been spotted in several parts of the country. There is also evidence that Russian forces are concealing their movements. “In recent days I have seen a lot of images which show Russian troops in their camps hiding in forests, from Belarus to Soloti”, notes Konrad Muzyka of Rochan Consulting, who tracks Russian military movements. “I think Russians are doing a good job in terms of operational security”.

Though Russia has consistently denied that it plans to attack Ukraine, Western security officials say that they have had insight into Mr Putin’s war plans for months, and that the Kremlin's aim is to install a pro-Russian dictatorship in Kyiv with Russian control down to the local level, backed with an occupation force if necessary.

Russian units in western Russia and Crimea are expected to mount a “double envelopment”, or pincer movement, against Ukrainian troops around Donbas, where the majority of Ukraine's most sophisticated and combat-ready troops are based, shattering them and cutting them off from the west of the country—including by seizing or destroying bridges over the Dnieper. The main thrust, officials say, will probably be directed at Kyiv, by Russian forces in Belarus, accompanied by intensive use of electronic warfare and air and missile strikes on military targets and critical infrastructure. On February 17th Britain’s defence ministry published a map showing Russia’s “possible axis [sic] of invasion” consistent with these suggestions.

Many Russian analysts express doubts about such grandiose plans. “I don't believe in a large-scale military march on Ukraine”, says Ruslan Pukhov, a defence expert at CAST, a think-tank in Moscow. “With such a march and any occupation of territory it is not clear what we will get out of it except more problems”. Ukraine’s armed forces have improved significantly since 2014, morale on the front line is high and they would fight. But they are lacking in air defences and are ill-prepared for the sort of sweeping combined-arms offensives and air-mobile assaults that Russia can mount. They are likely to fare poorly in the first phases of a war. However, it is far from clear that the Kremlin has a sober understanding of the degree of resistance it would then face. Less than 10% per cent of Ukrainians voted for pro-Russian parties in the last elections. Kyiv has also been preparing for an invasion for eight years, with the infrastructure of a guerrilla campaign already in place. How successful it could be depends on many factors, including the region in question. Just as important is the degree of support extended by friendly countries, such as America, Britain and Poland. “There are remarkably few historical cases of resistances that, by themselves, defeat the more powerful occupier”, notes Brian Petit, a retired American special-forces colonel, in an essay for War on the Rocks, a website. “As a rule, it takes external support to tip the scales in favour of the resistance”. Such external support may be aimed at simply bogging down Russia in a protracted and bloody occupation. Biden administration officials have suggested that the Pentagon and CIA would provide arms and other help to any Ukrainian insurgency, much as they aided the anti-Soviet mujahideen during the occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. That may depend in part on what remains of the Ukrainian government. Poland and the Baltic states would also probably offer support. So, too, would Romania, says Jonathan Eyal of the Royal United Services Institute, a think-tank, who notes that the country shares the longest—and most mountainous—border with Ukraine of any European country. “The key for Romania is Moldova”, he says. “If Ukraine falls to the Russians, Moldova is next”. Military tensions rose further as Russia began a large-scale strategic nuclear exercise on February 19th, involving cruise and ballistic missile launches to test the readiness of Russia’s air, sea and land-based nuclear forces. Though the “Grom” exercise is normally an annual event, it has been cancelled for the past two years because of the pandemic. That its resumption has coincided with the peak of this crisis is probably designed to remind America and NATO of the risks of escalation should a conflict arise—and thus the inadvisability of getting involved. Mr Putin, who is overseeing the drill, was pictured sitting with Alexander Lukashenko, the Belarusian president, in a command centre during the launch of a ballistic missile. A day earlier, Mr Lukashenko had repeated his offer to host Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus.

At the Munich Security Conference, an annual gathering of world leaders, diplomats and spooks which began on February 18th, the crisis dominated. Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, was due to attend, despite American entreaties to stay in his country. Russian pressure has forged a Western consensus on the importance of presenting the Kremlin with a common front and preparing punitive sanctions in the event of an invasion. “Transatlantic unity and cohesion have not been so palpable for a long time”, notes Jana Puglierin of the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank, reflecting on the mood at Munich. That cannot have been what Mr Putin intended.

Even so, most see a storm coming. Though Antony Blinken, Mr Biden’s secretary of state, plans to meet Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, in the coming days, America’s assessment that Mr Putin has already decided on war, and Mr Lavrov’s marginal role in the Kremlin’s decision-making, offer little encouragement. “For the first time in decades, we, regrettably, find ourselves on the verge of a conflict which can draw the entire continent into it”, warned Mr Lukashenko, as he sat next to an impassive Mr Putin on February 18th. America and its European allies find themselves in grim agreement.

Exxile4000 on February 20th, 2022 at 08:04 UTC »

So it was Metro 2023 not 2033. Books were a bit off

TheSirCheddar on February 20th, 2022 at 06:58 UTC »

Do any foreign countries have soldiers in Ukraine that will actively engage in defense of Ukraine?

-PM_ME_YOUR_TACOS- on February 20th, 2022 at 06:17 UTC »

These are strange times. I'm reading how the possible next WW is starting while lying down on my bed.