Barely a week after withdrawing nearly all U.S. forces from Afghanistan, President Biden faces, in Haiti, a strikingly similar dilemma, now much closer to home.

In Afghanistan, Mr. Biden concluded that American forces could not be expected to prop up the country’s frail government in perpetuity. His critics argue that withdrawing makes Washington culpable for the collapse that seems likely to follow.

There is no threat of insurgent takeover in Haiti. But, with authorities there requesting American troops to help restore order and guard its assets, Mr. Biden faces a similar choice.

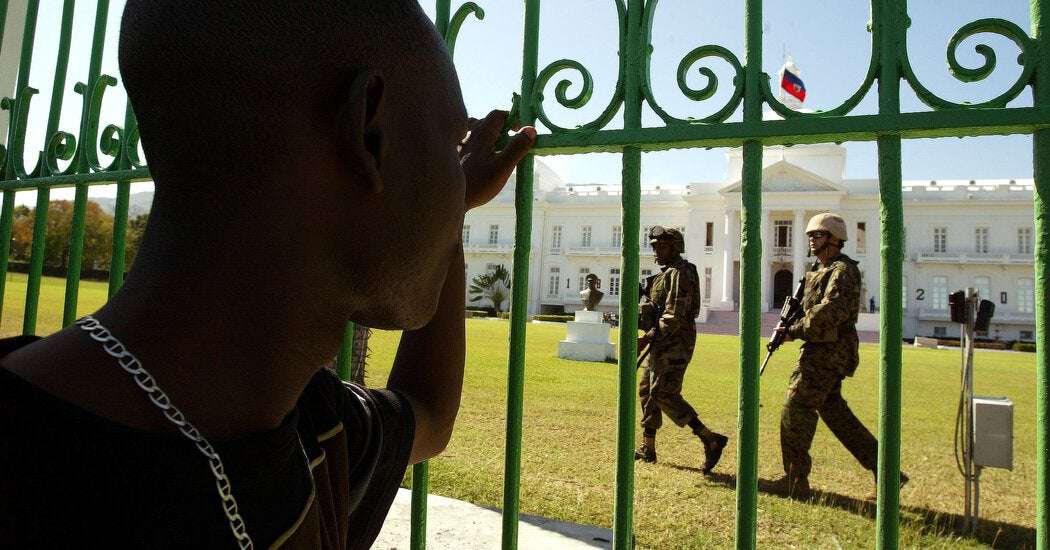

Past interventions in Haiti suggest that another could indeed forestall further descent into chaos. But those occupations lasted years, did little to address (and may have worsened) the underlying causes of that chaos, and left the United States responsible for what came after.

Pheww_ on July 23rd, 2021 at 17:32 UTC »

There's no real geopolitical benefit if the US decided to, except for maybe a military base or a puppet state with little to no worth. IMO, this should be a UN intervention, not a US one. More countries could help rebuild Haiti and to spread the cost of rebuilding.

DarkMatter00111 on July 23rd, 2021 at 15:07 UTC »

They need to send a United Nations task force there, that way all countries can have can have a say and everyone remain neutral. Blue Helmets, not US troops. Keep the peace.

PBRStreetgang67 on July 23rd, 2021 at 13:03 UTC »

For those outside the paywall:

Weighing Haiti Intervention, U.S. Again Faces a Torturous Dilemma

Time and again, the world has found that propping up failing states is compelling in the short term and potentially disastrous in the long term.

Barely a week after withdrawing nearly all U.S. forces from Afghanistan, President Biden faces, in Haiti, a strikingly similar dilemma, now much closer to home.

In Afghanistan, Mr. Biden concluded that American forces could not be expected to prop up the country’s frail government in perpetuity. His critics argue that withdrawing makes Washington culpable for the collapse that seems likely to follow.

There is no threat of insurgent takeover in Haiti. But, with authorities there requesting American troops to help restore order and guard its assets, Mr. Biden faces a similar choice.

Past interventions in Haiti suggest that another could indeed forestall further descent into chaos. But those occupations lasted years, did little to address (and may have worsened) the underlying causes of that chaos, and left the United States responsible for what came after.

Still, after decades of involvement there, the United States is seen as a guarantor of Haiti’s fate, also much as in Afghanistan. Partly because of that involvement, both countries are afflicted with poverty, corruption and institutional weakness that leave their governments barely in control — leading to requests for more American involvement to prop them up.

Refusing Haiti’s request would make Washington partially responsible for the calamity that American forces likely could otherwise hold off. But agreeing would leave it responsible for managing another open-ended crisis of a sort that has long proven resistant to outside resolution.

“The state has literally almost completely vanished,” said Robert Fatton, a Haitian-born political scientist at the University of Virginia. “And to some extent this is because of the pattern of assistance that was given to Haiti.”

The White House says it is working with Haitian leaders and the international community to guide Haiti out of crisis and toward deeper reforms. But there is little optimism that this will reverse the country’s trajectory.

Repeating History

The United States has faced versions of this dilemma in Haiti before, and with lessons that cut in both directions.

In 1991, a military coup removed Haiti’s elected leader, launching a reign of terror that killed thousands. Unwilling to repeat what he saw as Kennedy’s mistake, Mr. Clinton won United Nations approval to invade and reinstate democracy.

Initially, the intervention was greeted in Haiti and abroad as a stunning success that would finally set Haiti on a better path.

Skeptics of the intervention were cast as craven and shortsighted. Chief among them was then-Senator Joseph R. Biden, who drew rebuke from all sides for commenting, “If Haiti just quietly sunk into the Caribbean or rose up 300 feet, it wouldn’t matter a whole lot in terms of our interest.”

As Washington would later learn in Afghanistan, troops can pause unrest, but rebuilding a state can take generations. By the end of Clinton’s presidency, as the American occupation became a United Nations force, it was recast as a failure.

“The intervention in Haiti was a short-lived success,” James Dobbins, the U.S. envoy to Haiti at that time, later told Time magazine.

“The main lesson we learned from Haiti was the limitations of these kinds of interventions and what you could expect to achieve,” he said. “And to learn that the transformations would only be partial and would take a long time.”

Many experts now believe that the intervention, though superficially successful, worsened the underlying problems that had compelled Mr. Clinton to act in the first place. The reinstated leaders, now backed by American force, felt freer to act as they wished. American-pushed economic reforms flooded the country with imported food and other goods that drowned out Haitian businesses.

As if to demonstrate that there are no easy answers to such crises, Mr. Clinton took the opposite approach in Afghanistan. When his administration faced pressure to intervene in a civil war as a new insurgent faction took the upper hand in the country’s south, Mr. Clinton refused. Though American support of guerrillas there during the Cold War had helped instill many of the country’s problems, he believed it was beyond the United States’ remit.

Three decades later, that insurgent faction, the Taliban, seems bent on conquering Afghanistan for a second time. Mr. Clinton’s legacy bears the accusation from Afghanistan experts that Mr. Biden faced from Haiti’s supporters in the 1990s: of abandoning a country to which Washington owed support after so drastically steering its fate.

Repairing Broken States

Haiti’s experience has not been so dire. But it fared little better under American occupation than Afghanistan did under American inaction.

As often happens with peacemaking interventions, the forces that Haitians had once greeted as saviors, Dr. Fatton said, became “resented as a foreign occupation, really hated.”

Peacekeepers, aid agencies and development experts tried virtually everything over the 20-plus years in Haiti. They invested in bureaucratic institutions and small start-ups. They pursued democracy reform, trained election overseers and promoted grass-roots groups.

In an attempt to roll back criminals that had seized control of Haiti’s vast slums, peacekeepers even cleared the worst gangs and restored long-receding government authority.

“For a while they managed to control the streets and there was a semblance of normalcy,” Dr. Fatton said.

Some police officers, who were no longer responsible for policing thanks to the U.N., but many of whom faced deep poverty and hunger themselves, opened their own criminal enterprises to fill the void.

And the peacekeepers could not stay forever.

“Once they exited, it got very messy again and the gangs are even more powerful than they were,” Dr. Fatton said.

This has been the pattern across many areas of foreign assistance, he added: “The institutions were already weak, so they started to really fall apart.”

Throughout much of the U.N. presence, experts warned that every year the foreigners stayed, Haiti grew more reliant on them for day-to-day governance. This allowed Haitian institutions to decay further and refocus on corruption, often by extracting the foreign aid that became one of Haiti’s most valuable resources.

But each year also made it harder to leave, knowing that the U.N. would be blamed for once more abandoning Haitians.

The U.N. force finally left in 2017, chased out by scandal and grass-roots opposition to their presence. Now, only four years later, Washington and the world once more face demands to fill the void that Haiti cannot.

“You have a state that has been eviscerated,” Dr. Fatton said.

TL:DR - Intervention in Failed States - Damned if you do, damned if you don't.