If there’s one thing that most people think they know about the early history of Australia, it’s that the continent remained suspended, in unchanging isolation, for countless thousands of years before the arrival of the convicts of the First Fleet early in 1788. Cut off from the rest of humanity ever since the end of the last Ice Age, the Aboriginal population lived on for generation after generation in a hazy, mythic stasis: a “Dreamtime” in which the passage of the years, and even the notion of history itself, had practically no meaning. Theirs was a pure, pristine existence; the first Australians were part of the land itself, rather than living off it and exploiting it. And when the British arrived and claimed the continent, they sullied an Eden, degrading the noble savages who lived in it.

There is plenty that is wrong with this portrait of pre-contact Australia. It owes more to the New Age enthusiasms of the 1970s than it does to the realities of history. It lumps together hundreds of tribes, and dozens of major language groups, into one undifferentiated mass – conflating lives lived in an almost infinite variety of landscapes, from the deserts of the red centre to the lushness of the tropical north – and it perverts a rich, complex mythology, turning what we inadequately term “the dreaming” into little more than a synonym for the whole period before the days of Captain Cook. Most dangerously of all, it imposes striking limitations on the Aborigines themselves. In insisting they were pure, it makes them primitive; in sketching them as absolutely isolated, it encourages us to think of them as people so alien that they were barely capable of interacting with the rest of the world.

All this is a distortion of a less straightforward but vastly more compelling history. Australia was never entirely cut off from the rest of the world; there is evidence of frequent contact with the peoples of New Guinea and, beginning in the 17th century, there were also sporadic encounters with Dutch mariners along the western and northern coasts. Most remarkably of all, the Aboriginal peoples of the far north – what Australians today call the “Top End” – were, for several centuries at least, part of a vibrant and extensive trading system, one that brought them into annual contact with seagoing merchants from Indonesia, and linked them to civilisations as far away as China and Japan.

This is a history that remains comparatively little-known, not least because it involves no Europeans. But, since it so subverts the popular conception of what actually went on in Australia, it is a story well worth telling. In this history, Aboriginal Australians not only met and worked – often on terms of easy friendship and equality – with peoples from cultures quite different from their own; they also lived and sometimes travelled with them. Perhaps the most startling outcome of this series of events was a surreal encounter between the first group of white explorers to penetrate the deep interior of the north and an Aborigine who – they were amazed to find – already spoke a little English, picked up in the course of a voyage he’d made to Singapore. But surely the most fascinating was the creation (decades, probably, before Cook came ashore at Botany Bay, and perhaps as early as the 17th century) of a small Aboriginal community in the busy port of Makassar, in Sulawesi: that extraordinary island, all peninsulas, that lies in the heart of the East Indies, and looks like nothing so much as a child’s sketch of a dinosaur.

The events that produced this history have their roots in the China of the Ming dynasty. There, at some point late in the 1500s, cooks first began to use sea cucumbers as ingredients in glutinous soups. These animals – noted for their ability expel their own intestines when threatened with attack, and also known as trepang or as bêche-de-mer – live at the bottom of shallow seas, and are found in vast quantities throughout much of south-east Asia. Typically cylindrical, with leathery skins covered in chalky warts, trepang are not the most obvious of foods; western sources are unanimous in describing them as physically repulsive, and Darwin’s rival Alfred Russel Wallace memorably likened them to “sausages which have been rolled in mud and then thrown up the chimney.” In Chinese culture, however, they are believed to possess considerable virtues. Cooked, they acquire a jelly-like texture that helps to bring out the flavours of other ingredients. They were also thought to have medicinal properties, not least in boosting the male libido. A treatise composed in 1757 advised: “The medical function of trepang is to invigorate the kidney, to benefit the essence of life, to strengthen the penis of the man, and to treat fistulas.”

Belief in these remarkable properties spurred a strong growth in demand. For much of the 17th century, this was met by exploitation of local sources, not least the shallows that surround the southern Chinese island of Hainan. But there are hundreds of species of trepang, each with its own properties, and Chinese merchants soon began to seek fresh sources of supply. The animals were being harvested in the Moluccas as early as 1636, and from the waters around the island of Flores by the 1720s. A lively trade in trepang was also underway in Makassar by the first years of the 18th century; port records show that, by 1717-18, catches totalling 11 tonnes were unloaded on the wharfs. The market grew rapidly thereafter – to almost 300 tonnes a year in the mid-1770s, and to about 450 tonnes a decade later. Since rough calculations show that there were something like 28,000 dried trepang to the tonne, the total annual catch traded in this one port must have surpassed one and a quarter million animals at this point, and, by the end of the century, trepang was by a distance the most important commodity in the Makassarese economy. Some 30 different varieties were traded in the Indies, and Chinese merchant junks were calling at dozens of ports to hoover up supplies.

The Makassans who dealt in trepang were the unwilling subjects of what was then the largest corporation in the world – a Dutch monolith called the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, the United East India Company, or VOC – and this fact helps to explain why the trade grew in the way it did. Like its British equivalent in India, the VOC was a merchant company that operated like a state, building its own army and navy and using them to seize control of the key ports and territories that it needed to dominate the chief luxury trades of the day – most notably the business in spices such as nutmeg, cloves and cinnamon, which fetched enormous prices throughout Europe. Dutch ships had first arrived in the East Indies at the tail end of the 16th century, fighting wars to oust the Portuguese. They established their main base at Batavia in Java, but found themselves increasingly irritated by the survival of the independent power properly known as the Kingdom of Gallo and Talloq. This state – which straddled the Gowa River in southern Sulawesi, is therefore often known as “Gowa,” and had Makassar as its capital – was already a major player in south-east Asia. Its roots can be traced back to the early 14th century; it benefitted considerably from the fall of the major local entrepôt, Malacca, to the Portuguese in 1511; and the conversion of its kings to Islam in 1604 or 1605 provided the impetus for several wars of conquest that ended with the subjugation of its chief rivals in southern Sulawesi. Located at the centre of the Indies, on sea lanes that stretched east-west from Malaya to New Guinea, and from Timor in the south all the way north to the coast of China, the Gowan sultanate was by the 1650s the most powerful independent state state in the Indies.

For the Dutch, Gowa was more than a trading rival, a stable and ambitious polity that espoused free trade and so had the potential to disrupt and undercut the lucrative monopolies that the VOC was building in Batavia; it was a potent threat to their company itself. Eager to play off European rivals against one another, its sultans allowed first the British, then the Danes and Portuguese to set up trading “factories” in Makassar, and by the time of Sultan Pattingalloang (who died in 1654) the port had become remarkably cosmopolitan. Makassan merchants funded as many as 250 trading voyages every year, their ships sailing as far as Cambodia and Macau. The town had both Portuguese and Chinese quarters; a Jesuit account dating to this period notes that Makassar also boasted “rice, palms, no pigs, numerous cattle, an infinity of chickens, many kinds of fish, a moderate air. Men go the upper part of the body naked; women are modest.” On top of all this, Pattingalloang was spending heavily on his defences. He bought up surplus European ordinance, cast cannon of his own, and commissioned a translation into Makassarese of a Spanish gunnery manual.

All this was intolerable to the VOC. The Dutch recruited local allies, placed Makassar under siege in 1664, and maintained a three-year-long blockade of the port. The war was decided by a decisive VOC victory in a sea battle fought in 1667; Makassar itself fell to an assault two years later, and the last Sultan of Gowa was forced to abdicate and died soon afterwards. The most important clauses in the peace treaty forced the Makassans to place their trade under the control of the VOC, which built a fort, installed a garrison, and appointed a harbourmaster to ensure that it seized full control of the lucrative spice business. Makassan ships were henceforth required to apply for a company pass in order to trade – an edict that effectively froze them out of any commerce that the Dutch preferred to focus on Batavia. It is in this context that we need to see the growth of the trepang industry, which rapidly became one of four major “private” native trades that flourished in Sulawesi. By the early 18th century, it was commerce in trepang, agar-agar (edible seaweed), karat (brilliantly-coloured tortoiseshell, sourced from the hawksbill turtle and used to make combs) and birds’ nests that kept the port alive. The Dutch had little interest in any of these trades. All four were financed by Chinese capital, and the harbourmasters’ records show that passes were freely granted to the native sailing ships – the praus – that dealt in them. These passes were rarely checked on the praus’ return.

In these circumstances, both an official and a pirate trade in trepang blossomed in Dutch-controlled Makassar. This commerce was lightly regulated and relatively lightly taxed. VOC habourmasters’ records show that the first official licences to import trepang were issued as late as 1710, but the likelihood is that a shadow trade existed beyond the purview of the port’s new masters for several decades before that. And the trepang trade grew rapidly. It was worth 3,500 Dutch rixdollars a year in 1720 – very roughly £60,000/$75,000 now, though the cost of living in 18th century Makassar was so low that such comparisons are almost meaningless. The same trade was valued at 78,000 rixdollars in the 1760s, and at 173,000 a year during the 1780s, meaning that it increased fifty-fold in little more than have a century. By 1800, trepang brought in well over twice as much as any other product sold on the local market.

As demand for sea cucumbers boomed, fleets began venturing further and further from home in search of new sources of high-quality catch. They were aided in these efforts by Gowa’s traditional allies, a tribe known as the Sama Bajo, or “sea gypsies,” whose headquarters were often clusters of huts built on stilts in coastal shallows. The Sama Bajo spent most of their lives on their boats, so much so that they were popularly supposed to experience “landsickness” when they came ashore; they had an unmatched reputation as navigators and explorers. The Sea Gypsies certainly knew all the waters of the Indonesian archipelago, and – since the northernmost shores of Australia are only about 400 miles (650km) from the southern tip of Timor – it is more than likely that it was they who first discovered rich beds of trepang along two stretches of coast that they called Kayu Jawa (modern Kimberley) and Marege’ – the blunt northern Australian peninsula that is now called Arnhem Land.

The voyage from Makassar to Marege’ typically took 10 days and was made far easier by the advent of the North-West monsoon, which blew strongly in the right direction throughout December and January. It involved sailing east, then south, for almost 1,000 miles (around 1,500km), navigating largely by oral tradition, and making a landfall somewhere between Bathurst Island and the Cobourg Peninsula. There a fleet that numbered perhaps 20 ships in the first days of the industry, but which grew to be more than sixty strong in time, would disperse and its praus would continue east in groups of three or four, stopping for a few days at a succession of suitable points to catch and process trepang before moving on, ending the four-month fishing season scattered from Groote Eylandt and Blue Mud Bay to the far south of the Gulf of Carpentaria. When the winds shifted and the South-East monsoon began in April, the praus would head home to Makassar.

In time, years of experience combined to make the voyage an efficient one. The Makassans learned to favour Arnhem Land, where the Yolngu peoples were broadly welcoming, over the Cape York Peninsula, further east, whose Wik peoples were very often hostile to incomers. They learned to select beaches that offered shelter from the north-west trades, a ready source of timber in the shape of mangrove swamps – and a clear field of view. This latter requirement, which emerges clearly from reinvestigation of the dozens of surviving trepang sites, indicates that relations between the Makassans and the local people were not always untroubled, and that basic defensive precautions were considered important.

According to the oral traditions of the Makassans themselves, fishing got underway with ritual offerings for a good catch and fair winds. These usually consisted of plates of the best food available, which would be lowered to the bottom of the sea on the first morning at each landing place. A little trepang could be harvested in the shallows at low tide – fishermen felt for the animals with their toes, and jabbed at them with weighted spears – but most was brought up from depths of anything up to 60 feet by specialist divers working from the half-dozen dugout canoes carried by each prau. On a good dive, these men could return to the surface with as many as 10 sea cucumbers, but the usual number was only two to four. As many as half of all the men in the fleet worked as divers, and a few calculations based on the known size of the catch suggest that, at the height of the trade, the Makassans would make as many as 20 dives per man per day for the duration of the four-month season – a tough job, but not an impossible one.

The next phase of the work was preparing and preserving the catch, which was done by first boiling and then smoking it. This was a process that took up to two days, and it made the Makassans’ camp sites home to what can fairly be described as Australia’s first industry. The work was skilled, and it involved more than simply drying the trepang so it would survive the voyage home. The “grey” sea cucumbers indigenous to the Australian coast was not of the highest possible quality (that honour belonged to the “white” trepang native to the Spermonde Archipelago, off the west coast of Sulawesi), but the right preparation could considerably boost the price of the finished product. Work started within an hour of the catch being brought to the surface; the trepang was paddled to shore and then boiled in large iron cauldrons, placed over mangrove fires kindled in specially-constructed stone hearths. After an hour or two in the seething brine, they were drained, then gutted, and then buried for a day or so in a pit dug on the beach. Exhumed, the trepang was washed to remove its tough outer skin before being returned to the boil for another 8 or 10 hours. This time it would be cooked with some red mangrove bark, which coloured the finished product and was thought to help preserve it.

The final stage of the process was smoking. A group from each prau’s crew would be assigned the task of constructing a bamboo smokehouse, using materials that appear to have been brought all the way from Sulawesi for the purpose. These men supervised the smoking of gutted and dyed trepang over a slow fire. The end product – a dry, shrivelled, dirty red sliver of flesh – would keep indefinitely: certainly for long enough to make the voyage home to Makassar, survive the wait for the annual Qing trading junk that came all the way south to the Indies to pick up the year’s catch from Marege’, and finally make the return journey back across the South China Sea to the junk’s home port of Amoy (today’s Xiamen) and into Chinese cooking pots.

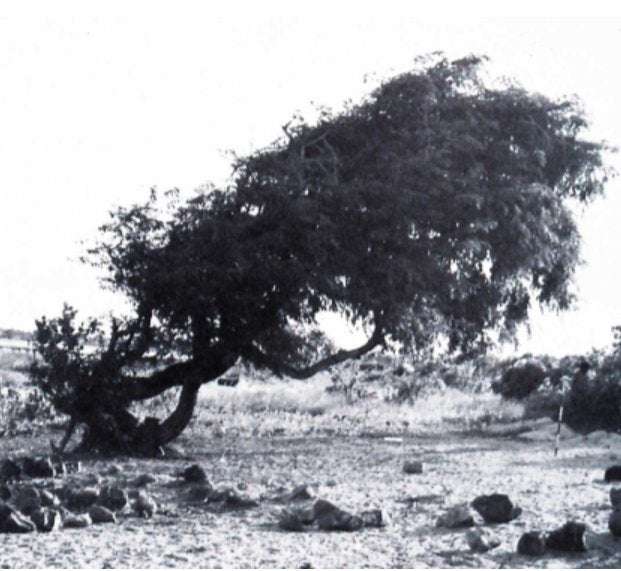

Years, then decades, and eventually centuries of contact not only regularised the trepang trade; it also created lasting relationships between the Makassans and the Aboriginal peoples whose lands they visited. The captains who ran the Makassan trade spent so long on coast of Marege’ that they left tangible evidence of their desire to turn it into a home from home in the stands of tamarind trees (not native to Australia) that can still be seen at many of the beaches where the trepangers camped, and must have been deliberately grown from seeds brought all the way from the Indies with the intention that, years later, the trees would grow the fruits needed to flavour the Makassans’ rice. Such men also had every motive for building strong relations with the local people. Friendly dealings meant that the Makassans could scale back their defensive precautions, maximising the number of men available to run their trepang fisheries; they also encouraged trade, not least in tortoiseshell and sandalwood, which seem to have been sourced over the course of each year and bartered to the trepangers when they returned. Finally, amicable dealings with the Yolngu opened up the possibility that additional supplies of labour could be made available when necessary.

The evidence we have suggests that the Makassans and the Aboriginal Australians were not invariably friendly. Flashpoints did occur from time to time, generally as a result of a breakdown in trust or poor treatment of one side by the other. Two survivors from a prau whose crew had been overrun by a Yolngu attack were brought to Darwin in 1869. Another, probably not isolated, incident was uncovered a few years later when the local collector of customs, Alfred Searcy, enquired about a grave he saw on a beach in Arnhem Land. An Aboriginal informant explained that

“a native one day was teasing the master [of a prau] for grog and tobacco, till, wearied with the black’s importunity, he struck him. The native did not appear to have taken offence at the time, but shortly afterwards he induced the captain to go into the bush with him on some pretext and when there, a number of natives set upon and murdered him. They then went on board the prau and murdered the cook and helped themselves to stores.”

Of course, the Makassans usually outnumbered the indigenous peoples in the immediate vicinity of their landing places, and they invariably exacted vengeance in such cases, but there is a good deal of evidence of close collaboration, too. One prau captain was reported by his son to have been “very good friends with the chieftain [of Dalumbu Bay, Groote Eylandt] … a man called Bankala, and they treated each other like brothers.” On the Australian side, Lazarus Lamilani – a native of Arnhem Land born in 1913, six years after British government attempts to tax the trepangers finally brought the trade to its end – learned from his youth that “the Aboriginal people were very friendly with the Makassans. They used to address them by the words for brother, uncle and father.” There are even reports of Makassan deserters joining Aboriginal tribes, and the archaeologist Campbell Macknight has collected accounts of curious Makassans living temporarily with Aboriginals in 1818, 1824, 1828, 1867-69 and 1915. A man named Timbo, who in 1839 helped the local peoples to navigate the strange environment of the new British settlement at Port Essington, got on with them so well that he decided to winter in Australia and learned enough of the local language to be “enticed away” into the interior, returning two or three months later with “glowing accounts” of life inland. Similarly, two Makassan boys are said to have been brought up among the Aboriginal peoples of Groote Eyelandt, and to have later acted as intermediaries and interpreters.

Sexual contact between the local people and men from the praus seems to have been relatively common. There are several accounts of Makassans fathering children by Aboriginal women; one, by the name of Using Daeng Rangka, had 10 children by three different mothers, and a daughter born from these unions, Kunano, journeyed to Makassar to stay with him in about 1903. The anthropologist Diane Bell points to the likelihood of homosexual encounters, too, seeing linguistic evidence of Malay input into local phrases meaning “smooth anus” and “anus with semen.” Unsurprisingly, the Makassans also appear to have been responsible for introducing previously unknown venereal diseases, as well as smallpox, into Arnhem Land; the declining birth rate evident on Golbourn Island in the 19th century has been attributed to the advent of gonorrhoea. And, over time, contact between the two groups was sufficiently intimate and sufficiently protracted for numerous other Malay words to enter the local languages. Macknight notes the telling presence of verbs meaning to work, to write, to guard, to count, to fish, and to be in charge of something.

It is not surprising, then, that Aboriginal Australians were willing to work alongside the trepangers if invited to, exchanging their labour for useful items such as fish hooks, knives, cloth, tobacco and food. (Alcohol was sometimes bartered, too, but apparently relatively rarely.) Such encounters may have been infrequent and occasional – Macknight points out that the Makassans brought their own manpower with them – and when they did occur, it was not necessarily on the basis of equality; the Aboriginals appear to have viewed the Makassans as members of another tribe, not entirely unlike them, but accounts from the trapangers suggest they sometimes feared the local people as cannibals, and often termed them “orang outan,” a dismissive term meaning “bushmen.” But they did take place, and sometimes they involved the same groups of trepangers working for years with the same local helpers. The French explorer Dumon d’Urville, who visited the Top End in 1844, observed 27 Aboriginal men rendezvousing with four praus, and working alongside their crews for the whole of a four-day stay.

It was collaboration of this sort that led to the journeys undertaken by small groups of Aboriginals to Makassar. The small scattering of reports we have suggest that these were never especially rare. A Dutch administrator who visited Sulawesi in 1824 seems to have been the first to note the presence of Australians there: “very black, tall in stature, with curly hair, not frizzy like that of the Papuan peoples, long legs, thick lips, and, in general, are quite well built.” And when a British army officer, Collet Barker, questioned the captain of a Makassan prau at Raffles Bay five years later, his informant “described a very good run of blacks (in the Gulf of Carpentaria as well as I could make out) who wore clothes, spoke a little Malay, drank arrack, never stole from them, and made themselves useful in various ways… These people would come on board, men, women and children, before they came to anchor. Several had been at Macassar, probably 100 of them; some were there now. They were useful sailors.”

Similar reports crop up here and there throughout the 19th century. Joseph Jukes – a geologist about the British ship HMS Fly, which surveyed the coast of Arnhem Land in 1845 – witnessed a Makassan prau disembarking a man who had sailed to Sulawesi the previous year, and added: “This we are told was not an uncommon occurrence, as the natives of Port Essington are very fond of going abroad to see the world.” There were at least 17 Australians living in Makassar in 1876 under the protection of another prau captain, Unusu Daeng Remba, and in 1900 there were three, staying with Daeng Tempo, who was then one of the main organisers of the Marege’ trepang trade. Some anthropologists hint that these men may have been prisoners – in effect slaves – but the evidence we have does not support this. Rather, it suggests that these men worked in exchange for their board and lodging; one Makassan account tells of two Australian travellers, named Lahurru and Lakkoy, who guarded the fish ponds at the back of their employer’s house and pumped water for him.

Macknight points out the consequences of all this contact for the Aboriginal Australians who travelled with the praus: “The men concerned knew a great deal about the world beyond the small society they had left behind. By necessity they picked up new languages and experienced social relationships of a kind unknown at home. They observed, even if they could not fully understand, the economy and technology of [Sulawesi] and elsewhere. The tone of their response – excited, relying on particular friends for company and advice, observant of names and details but confused as to its true relationship and unsure of peoples’ true motives – comes out clearly in their reminiscences.”

This tells us almost all that we know about the views of the Aboriginal peoples themselves on their experiences of voyaging and their visits to the Indies. But we do have one final piece of evidence that tells us a little more about the experiences that these early visitors had in Sulawesi. This is a set of photographs of a group of voyagers, taken in Makassar in 1873 by an Italian ethnologist named Odoardo Beccari. Beccari noted that Australians were a common sight in the streets of the town at about this time, and secured the co-operation of five of them – a man and four boys – who hailed from the Cobourg Peninsula. From the photographic evidence, one seems to be as young as four or five. But all the members of the group look healthy and well treated, and they do not seem fazed by their encounter with a European, nor especially unhappy to have been asked to stand in front of a camera while their portraits were captured. They seem to be as much a part of 19th century Makassar as anybody else.

All this begs one question – when might Aboriginal voyages to Makassar have commenced? There is no way of answering definitively; all we can say for certain is that there is no good reason why visits should not have begun well before the first dated encounter that we know of, in 1824. Beyond that, very little seems unchallengeable; even the date when the Marege’ trepang trade itself commenced is hazy, and there are tantalising hints that voyages to the Australia’s inhospitable north coast may perhaps have antedated the quest for sea cucumber; there may have been fewer reasons to risk such a voyage, but the idea of a disabled prau making landfall, and managing to return, is not preposterous. There were also rumours that a land stuffed with gold existed somewhere to the south of all existing maps. Such tales were in circulation as early as the 13th century, and were quite prominent by the 15th; who knows who may have been inspired to explore to the south of Timor by them?

Let us begin an investigation of this evidence with some exact dates. The Makassan captain Pobasso – encountered and interviewed in the middle of a trepanging voyage by the British naval captain Matthew Flinders in 1803 – indicated that the trade had become widespread only a few decades earlier, and indeed the earliest account we have that unquestionably refers to a voyage to Marege’ or Kayu Jawa dates to 1751, when a Chinese trader who set out from Timor in search of tortoiseshell found himself – “after five days’ sailing before the wind and two days and nights having drifted” – on an unfamiliar shore where the people were “very black, large and robust, unclothed, unarmed, with long wooly hair.” A Dutch resident on Timor who commented on this encounter seems to have some knowledge of a pre-existing Makassan trade with the same coast, but this, he added, took place only “weel ens” – “now and then.”

We can certainly suggest that regular trading voyages to Marege’ can scarcely have begun prior to 1600, when the sea cucumber first featured on Chinese menus, and probably not for several decades after that, when demand first began to boom. A massive Dutch account of the Indies trade, compiled by Cornelis Speelman in 1670, just after the Dutch conquest of the Gowa sultanate, makes no mention of trepang. On the other hand, Campbell Macknight picked up several traces of an oral tradition – about two centuries old by the time he heard it – which held that elements of the Gowan forces defeated in the great sea battle of January 1667 fled south and found their way to the Gulf of Carpentaria. The names of the leaders of this Makassan “first fleet” seem to be preserved in the names that later voyagers gave to local features in the 18th and 19th centuries. Eventually, the same account concludes, these praus made their way cautiously home, bringing with them the first cargo of trepang ever seen in Sulawesi.

Reviewing all of these considerations, Macknight tentatively places the earliest regular voyages from Makassar to Marege’ in the last quarter of the 17th century – perhaps a little later. The numbers of praus involved must have remained relatively small; the habourmasters’ records show that at least 90% of the trepang traded at Makassar in the 1760s undoubtedly came from sources other than the Australian coast, and 81% in the 1780s. The annual Amoy junk – essentially a mobile trading community, stuffed with independent merchants and 60,000 rixdollars’-worth of Chinese goods, which was the crucial final step in the trepang trade – only began its voyages to the Indies in 1736, and did not call regularly at Makassar until the 1770s. This suggests that large scale importation of Australian trepang into Qing China is unlikely to have begun much before the middle of the 18th century.

Yet there is other evidence that contradicts this. Joseph Needham points out that, prior to China’s decision to turn inwards early in the Ming period, it had already established trading routes that stretched from the Philippines to Timor, and that it was importing birds’ nests from Borneo as early as 1200. A map [above left] showing the territories subject to the sultans of Gowa – a modern production, but one that claims to be based on contemporary records – hangs today in a reconstruction of the sultans’ palace; it clearly shows Marege’ and dates its “accession” to the Gowan empire to 1640.

Rather more telling is the evidence supplied by anthropologists and students of linguistics. The former point to a cycle of Top End Aboriginal legends involving the “Baijini,” a “pale people” who came to Australia before its history proper began, built stone houses, made cloth, and collected trepang. Who the Baijini might have been remains a matter of controversy. Some see them as early Chinese traders, others as Indonesian sea gypsies. Berndt argued that their visits ceased shortly before the Makassans first appeared, but helped to pave the way for them; both Hiscock and Macknight conclude that the legend-cycle is most likely based upon distorted memories of early visits by Makassans, and of Aboriginal voyages to Makassar. One piece of evidence suggesting that Macknight is right is the mention of animals that sound like elephants in one song-cycle: beasts with “big teeth” protruding from their “nostrils.”

The biggest of these disputes is still rumbling on, and involves attempts to date artefacts found at known Makassan trepanging sites in Arnhem Land. These have produced some truly anomalous results. Mulvaney dates a Makassan-style bronze fish hook to around 1000 AD; a thermoluminescence test run on a pottery shard from the East Indies found on Groote Eyelandt yielded a date range of 1086-1146. Three different efforts to carbon-date charcoal from Makassan boiling pits produced dates as early as 1170 and no later than 1520, and an analysis commissioned by Clarke and Federick on a sample of beeswax applied to an Aboriginal rock drawing of a prau was returned showing, with a certainty put at 99.7%, that the image had been made between 1517 and 1664. Finally, a Makassan skeleton dug up from an Australian beach – readily identifiable by its betel-stained teeth – has been dated to before 1730, with an 84% chance that it was interred prior to 1700.

It does not seem unlikely – especially given the sharply conflicting evidence of the historical record – that one or two of these samples might somehow have become corrupted, yielding anomalous dates. But how reasonable is it to dismiss all seven? Clarke – an anthropologist – argues that a long period of contact between Australia and Indonesia should now be seen as just as likely as the short period insisted on by the historical record; Macknight counters that many archaeologists like to push back dates as far as possible, and have an romantic, Orientalist vision of an “ageless Indies” that is scarcely borne out by the evidence.

Trying to draw some sort of conclusion from all this, it seems perfectly possible to suppose that at least a few travellers journeyed far from from their native Australia well before the first appearance of the British in the north – indeed, most likely long before Captain Cook appeared in 1770. It is less likely (but not, apparently, impossible) that the earliest of their visits to Indies ports such as Makassar may have pre-dated the colonial period that began in 1669. Either way, it seems entirely fair to view these “Dreamtime voyages” as things that took place entirely free of European influence, and which show the Yolngu of Arnhem Land as much more interesting, and far more formidable, than the “noble savages” of white Australian mythology.

Let’s conclude with the experiences of one Aboriginal Australian voyager – the only one, in fact, who lived to give his own detailed account of the trading links that sprang up between the Yolngu and the Makassans. His name was Charley Djaladjari, though he is better remembered as “Sit-Down Charley,” a name bestowed on him after he was a paralysed in a fall on board a Makassan prau. He gave his story to Ronald and Catherine Berndt, two anthropologists who did extensive work in Arnhem Land during the 1940s and 1950s, but his experiences date back to the late 19th century, and the last good years of the trepang trade. Charley’s record, note the Berndts, “is a particularly valuable one… There is a flavour of romance about the whole trip. He is an adventurer [who] … comes at last to a place that his people have glamorised.”

Charley’s adventure began some time around 1895, when he contracted with the captain of a prau to go on board for the return voyage to Makassar. The crew called at several other islands on the way – one (probably Maikoor Island) that lay en route to New Guinea, where Charley encountered men whose language he could understand, and another in what appears to have been the Banda Islands. When they reached Makassar, the local trepang trade boss, Karei Deintumbo Buga, came down to the wharf to greet them. “I’ve got some boys here,” the prau’s captain told him, to which Buga replied: “All right, I’ll take these men and they can come to my place to sleep and have food.”

When Charley and his comrades got to Buga’s home, they found a small community of Australians already living there:

“There was Jamaduda from the English Company Islands, who had come to Makassar as a small boy. He had worked there, and had never returned home. When I saw him he was a grown man: he had married a Macassan woman, and had four sons and four daughters. Then there was Gadari, a Wonguri-Mandjigai man from Arnhem Bay; he had come as a young man, worked there and married a Macassan woman. When I met him he was middle-aged and had a lot of children there… In the old days, before I went there, young unmarried men who came with the praus would often get married to the Macassan women and stop there; but usually the married men returned home the next season with the trading fleets. Sometimes young Aboriginal girls went to Macassar too, but most of them stayed there to marry Indonesians or to work about the town.”

Charley remembered that after unloading the trepang he and his friends were paid and “we had a good time, and a lot of drink, and slept with some Macassan girls.” He got a job boiling syrup and loading goods on the wharf, and stayed – in part, he said, because he acquired a taste for Indonesian food. In time, he had a family in Makassar before returning to Arnhem Land, where he had more children.

Charley’s story is the tale of a resourceful and adventurous young man, one who had the same desire to travel and enjoy new experiences that has driven other young men and women to leave their homes in thousands of communities for thousands of years. It is not the account of a man born into a society so isolated that he could never adapt or learn from other people. It explains a good deal about the motivations of the Aboriginal Australian voyagers. And it helps us to understand why, even today, the Yolngu say of the Makassans: “We are one people.”

Anon. “The conquest of Makassar by the Dutch (1596-1800).” Indonesia-dutchcolonialheritage.nl, accessed 27 July 2016; Odoardo Beccari. Nuova Guinea, Selebes e Molucche. Diari di Viaggio Ordinati dal Figlio. Florence: La Voce, 1924; Diane Bell. “An accidental Australian tourist: or a feminist anthropologist at sea and on land.” In Stuart B. Schwartz [ed.], Implicit Understandings: Observing, Reporting, and Reflecting on the Encounters Between Europeans and Other Peoples in the Early Modern Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994; Ronald M. Berndt. Djanggawul: An Aboriginal Religious Cult of North-Eastern Arnhem Land. London: Routledge, 1952; Ronald M. Berndt and Catherine H Berndt. Arnhem Land: Its History and its People. Murngin: FW Cheshire, 1954; Wayne Bougas. “Bantayan: an early Makassarese kingdom, 1200-1600 A.D.” Archipel 55 (1998); Jane Carey and Jane Lydon [eds]. Indigenous Networks: Mobility, Connections and Exchange. New York: Routledge, 2014; Marshall Clark and Sally K. May. Macassan History and Heritage: Journeys, Encounters and Influences. Canberra: ANU E-Press, 2013; Paul Clark. “Dundee Beach swivel gun: provenance report.” Northern Territory Government Department of Arts and Museums, 25 July 2013, accessed 31 July 2016; Anne Clarke and Ursula Frederick. “Closing the distance: interpreting cross-cultural exchanges through Indigenous rock art.” In I. Lilley [ed], Archaeology in Oceania: Australia and the Pacific Islands. Malden [MA]: Blackwell, 2006; Graham Connah. The Archaeology of Australia’s History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988; William P. Cummings. A Chain of Kings: The Makassarese Chronicles of Gowa and Talloq. Leiden: KITLV Press, 2007; William P. Cummings. [ed.] The Makassar Annals. Leiden: KITLV Press, 2010; James J. Fox. “Notes on the southern voyages and settlements of the Sama-Bajau.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 133 (1977); R.J. Ganter. “China and the beginning of Australian history.” The Great Circle 25 (2003); Regina Ganter and Julia Martinez. Mixed Relations: Asian-Aboriginal Contact in North Australia. Crawley [WA]: University of Western Australia Press, 2006; Enrico Giglioli. Viaggio Intorno al Globo della r. Pirocorvetta Italiana Magenta. Milan: Maisner, 1875; Geoffrey C. Gunn. History Without Borders: The making of an Asian World region, 1000-1800. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011; Hans Hägerdal. Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea: Conflict and Adaptation in Early Colonial Timor, 1600-1800. Leiden: KITLV Press, 2012; Peter Hiscock. Archaeology of Ancient Australia. London: Routledge, 2008; Alison Inglis and Susan Lowish. “Trepang: crossing cultures/creating connections.” Artlink 32 (2012); Gerrit Knapp and Heather Sutherland. Monsoon Traders: Ships, Skippers and Commodities in Eighteenth Century Makassar. Leiden: KITLV Press, 2004; Xavier La Canna. “Old cannon found in NT dates to 1750s.” ABC News, 22 May 2014, accessed 2 August 2016; Xavier La Canna. “Old coin shows early Chinese contact with Aboriginal people in Elcho Island near Arnhem Land: expert.” ABC News, 9 August 2014, accessed 2 August 2016; Marcia Langton and Robyn Sloggett. “Trepang: China and the story of Macassan-Aboriginal trade – examining historical accounts as research tools for cultural materials conservation.” AICCM Bulletin 35 (2014); Louise Levathes. When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997; Alessandro Lovatelli [ed]. Advances in Sea Cucumber Aquaculture and Management. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2004; C.C. Macknight. “Macassans and Aborigines.” Oceania 42 (1972); C.C. Macknight. The Voyage to Marege’: Macassan Trepangers in Northern Australia. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1976; C.C. Macknight. “Macassans and the Aboriginal past.” Archaeology in Oceania 21 (1986); D.J. Mulvaney and J. Peter White. Australians to 1788. Sydney: Fairfax, Syme & Welcon Associates, 1987; Joseph Needham et al. Science and Civilisation in China: IV – Physics and Physical Technology Part III, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971; Stuart B. Schwartz [ed.] Implicit Understandings: Observing, Reporting, and Reflecting on the Encounters Between Europeans and Other Peoples in the Early Modern Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994; Kathleen Schwerdtner Máñez and Sebastian C.A. Ferse. “The history of the Makassan trepang fishing and trade.” PLoS ONE 5 (2010); John Mulvaney. “Aboriginal Australians Abroad, 1606-1875.” Aboriginal History 12 (1988); D.J. Mulvaney. St Lucia: University of Queensland Place, 1989; Anthony Reid. A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2015; Heather Sutherland. “Trepang and wangkang: the China trade of eighteenth-century Makassar c.1720-1840s.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 156 (2000); Paul S.C. Taçon, Sally K. May, Stewart J. Fallon, Meg Travers, Daryl Wesley and Ronald Lamilami. “A minimum age for early depictions of Southeast Asian praus in the rock art of Arnhem Land, Northern Territory.” Australian Archaeology 71 (2010); Freja Theden-Ringl, Jack N. Fenner, Daryl Wesley and Ronald Lamilami. “Buried on foreign shores: isotope analysis of the origin of human remains recovered from a Macassan site in Arnhem Land.” Australian Archaeology 73 (2011); David Y.H. Wu and Sidney C.H. Cheung [eds]. The Globalization of Chinese Food. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

MeatThatTalks on February 14th, 2021 at 23:12 UTC »

Another bit of Australian Aboriginal language trivia:

When English-speaking linguists were studying the Mbabaram language and they asked them what they called a dog, the reply was... dog. They had a classic "who's on first" back-and-forth before they realized that there was no misunderstanding: the Mbabaram word for dog is just, by a sheer, crazy coincidence, exactly the same as the English word for dog.

AdvancedAdvance on February 14th, 2021 at 18:50 UTC »

I hope the first thing the Aboriginal said to the explorers was to please stop shouting "DO YOU UNDERSTAND THE WORDS THAT ARE COMING OUT OF MY MOUTH?!"

NolanSyKinsley on February 14th, 2021 at 18:38 UTC »

Reminds me of the pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock being greeted by a Native American named Samoset speaking perfect English asking them if they had any beer.