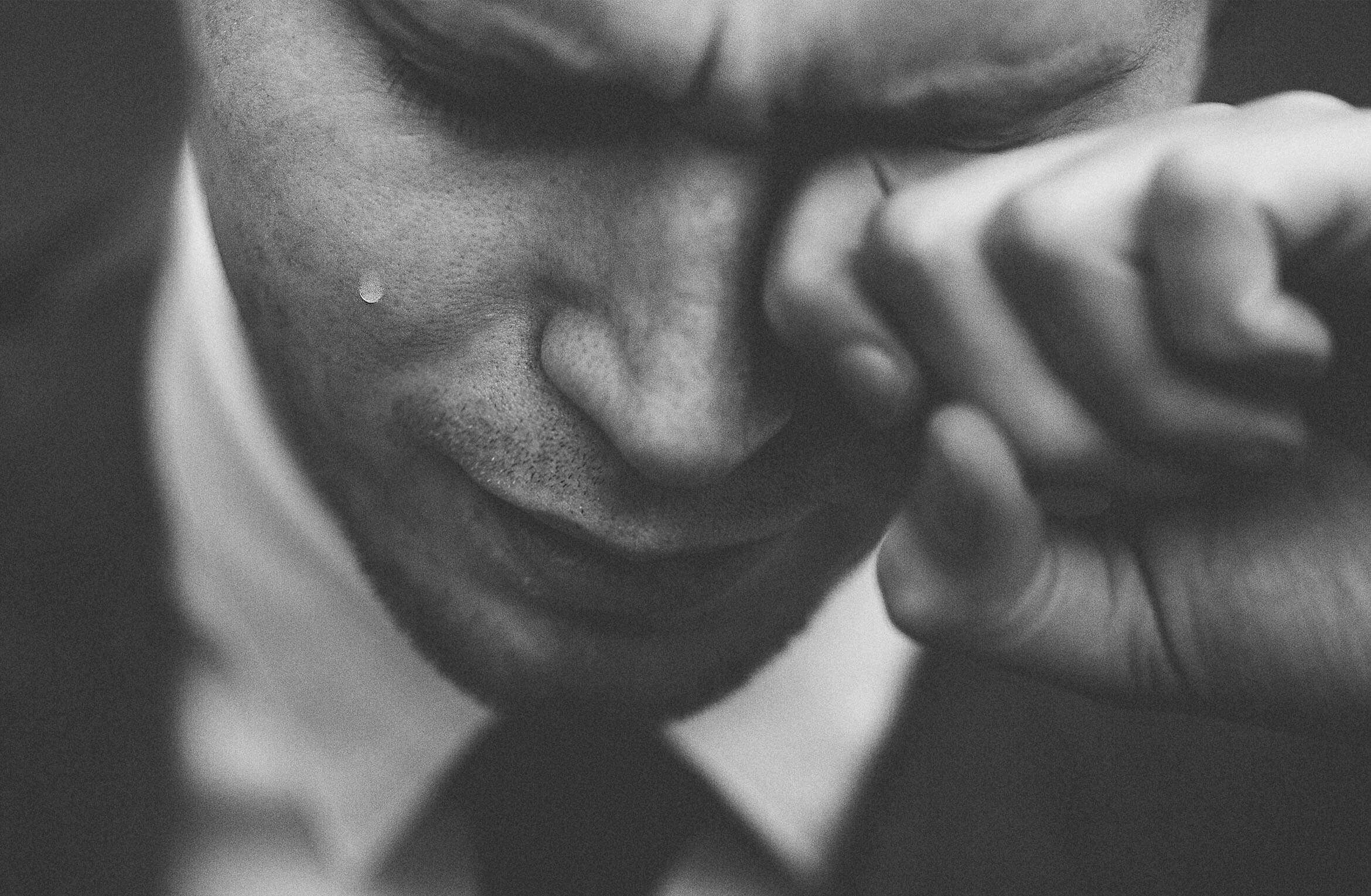

A new study discovered that people show unique gaze patterns when viewing crying faces, marked by a fixation on the person’s tears. The findings were published in Frontiers in Psychology.

Crying is a deeply human behavior that is thought to have several functions, including signaling the need for help. Existing research suggests that emotional tears act as unique signals that can trigger changes in an observer’s behavior. Study authors Alfonso Picó and team wanted to build on this research by exploring how the presence of tears would influence observers’ gazing behavior when it comes to viewing faces.

An eye-tracking study was conducted among a sample of 30 female undergraduate students. The students were fitted with eye-tracking equipment and shown a series of images of faces. The image set consisted of four photos of crying faces and duplicates of these photos but with the tears digitally removed. To isolate the effect of tears from other emotional expressions in the face, the researchers used images that depicted what they call “calm crying” — that is, the presence of tears in the absence of strong emotional expression.

Each image was accompanied by a one-line vignette (e.g., “I am not cheating on my boyfriend!”), and subjects were told to imagine that the exclamation was being said by the person in the photo. After viewing each face, the subjects rated the emotional intensity in the face and the sincerity in the face with regard to its accompanying statement.

At the end of the task, to examine whether subjects’ personality characteristics might influence their gaze patterns, the researchers had subjects complete measures of cognitive empathy and vulnerability to personality disorders.

The researchers found robust differences in subjects’ gaze patterns when viewing crying faces versus non-crying faces. First, participants spent more time gazing at the area around the eyes and right cheek — where the most prominent tear was located — on crying faces compared to non-crying faces. The subjects also displayed a higher number of fixations in this area, suggesting that the tears were capturing their attention.

The faces with tears were also rated more emotionally intense and more sincere than the faces without tears. “When [tears] were present, the inspection pattern changed qualitatively and quantitatively,” the researchers emphasize, “with participants becoming fully focused on the tears. The mere presence of a single teardrop running down the cheek was associated with increased emotional inference and a greater perception of sincerity.”

Interestingly, these inferences were influenced by the subjects’ personality characteristics. The higher a subject’s empathy score, the more emotionally intense they perceived the crying faces — and the less emotionally intense they perceived the non-crying faces. This suggests that those with higher empathy were better able to infer the difference in emotional intensity between the two faces.

Those with heightened tendencies toward personality disorders also showed unique gazing patterns, but only for the crying faces. For example, those who scored higher in antisocial personality spent more time gazing at the entire face and therefore less time gazing at the area of interest where the tears were. “We wonder whether this kind of personality increases the visual attention given to the whole face as a way of avoiding tearful eyes,” the authors reflect.

Picó and colleagues acknowledge that a larger sample is needed to further explore how personality characteristics might influence a person’s visual attention to tears. The researchers suggest that the next step for future research should be to include electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings in addition to eye-tracking to further advance the findings.

The study, “How Our Gaze Reacts to Another Person’s Tears? Experimental Insights Into Eye Tracking Technology”, was authored by Alfonso Picó, Raul Espert, and Marien Gadea.

papin97147 on December 18th, 2020 at 03:41 UTC »

If someone could tell me how NOT to cry in basically any heightened situation that’d be great.

ravinglunatic on December 17th, 2020 at 23:24 UTC »

They also show vulnerability. I’m afraid to see other people when I’ve been sad.

mvea on December 17th, 2020 at 22:22 UTC »

The post title is from the linked academic press release here:

Eye-tracking study suggests that other people’s tears act as a magnet for our visual attention

A new study discovered that people show unique gaze patterns when viewing crying faces, marked by a fixation on the person’s tears. The findings were published in Frontiers in Psychology.

Crying is a deeply human behavior that is thought to have several functions, including signaling the need for help. Existing research suggests that emotional tears act as unique signals that can trigger changes in an observer’s behavior.

The source journal article is here:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02134/full

How Our Gaze Reacts to Another Person’s Tears? Experimental Insights Into Eye Tracking Technology

Front. Psychol., 02 September 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02134

Abstract

Crying is an ubiquitous human behavior through which an emotion is expressed on the face together with visible tears and constitutes a slippery riddle for researchers. To provide an answer to the question “How our gaze reacts to another person’s tears?,” we made use of eye tracking technology to study a series of visual stimuli. By presenting an illustrative example through an experimental setting specifically designed to study the “tearing effect,” the present work aims to offer methodological insight on how to use eye-tracking technology to study non-verbal cues. A sample of 30 healthy young women with normal visual acuity performed a within-subjects task in which they evaluated images of real faces with and without tears while their eye movements were tracked. Tears were found to be a magnet for visual attention in the task of facial attribution, facilitating a greater perception of emotional intensity. Moreover, the inspection pattern changed qualitatively and quantitatively, with our participants becoming fully focused on the tears when they were visible. The mere presence of a single tear running down a cheek was associated with an increased emotional inference and greater perception of sincerity. Using normalized and validated tools (Reading the Eyes in the Mind Test and the SALAMANCA screening test for personality disorders), we measured the influence of certain characteristics of the participants on their performance of the experimental task. On the one hand, a higher level of cognitive empathy helped to classify tearful faces with higher emotional intensity and tearless faces with less emotional intensity. On the other hand, we observed that less sincerity was attributed to the tearful faces as the SALAMANCA test scores rose in clusters A (strange and extravagant) and B (immature and emotionally unstable) of our sample. The present findings highlight the advantages of using eye tracking technology to study non-verbal cues and draw attention to methodological issues that should be taken into account. Further exploration of the relationship between empathy and tear perception could be a fruitful avenue of future research using eye tracking.