Aphantasia – being blind in the mind’s eye – may be linked to more cognitive functions than previously thought, new research from UNSW Sydney shows.

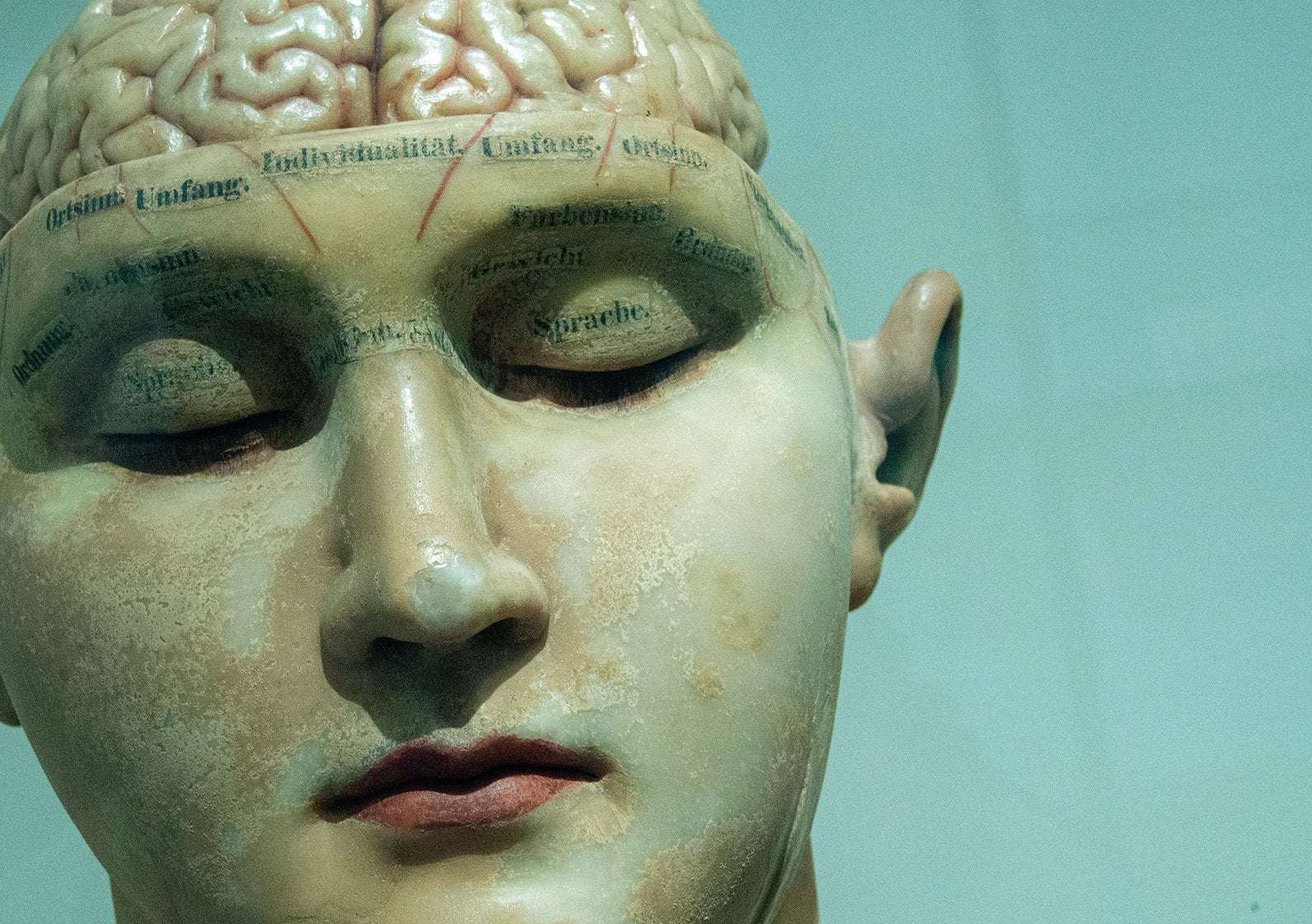

Up to one million Australians could have aphantasia, but we know very little about the condition. Photo: Unsplash.

Picture the sun setting over the ocean.

It’s large above the horizon, spreading an orange-pink glow across the sky. Seagulls are flying overhead and your toes are in the sand.

Many people will have been able to picture the sunset clearly and vividly – almost like seeing the real thing. For others, the image would have been vague and fleeting, but still there.

If your mind was completely blank and you couldn’t visualise anything at all, then you might be one of the 2-5 per cent of people who have aphantasia, a condition that involves a lack of all mental visual imagery.

“Aphantasia challenges some of our most basic assumptions about the human mind,” says Mr Alexei Dawes, PhD Candidate in the UNSW School of Psychology.

“Most of us assume visual imagery is something everyone has, something fundamental to the way we see and move through the world. But what does having a ‘blind mind’ mean for the mental journeys we take every day when we imagine, remember, feel and dream?”

Mr Dawes was the lead author on a new aphantasia study, published overnight in Scientific Reports. It surveyed over 250 people who self-identified as having aphantasia, making it one of the largest studies on aphantasia yet.

“We found that aphantasia isn’t just associated with absent visual imagery, but also with a widespread pattern of changes to other important cognitive processes,” he says.

“People with aphantasia reported a reduced ability to remember the past, imagine the future, and even dream.”

Study participants completed a series of questionnaires on topics like imagery strength and memory. The results were compared with responses from 400 people spread across two independent control groups.

For example, participants were asked to remember a scene from their life and rate the vividness using a five-point scale, with one indicating “No image at all, I only ‘know’ that I am recalling the memory”, and five indicating “Perfectly clear and as vivid as normal vision”.

“Our data revealed an extended cognitive ‘fingerprint’ of aphantasia characterised by changes to imagery, memory, and dreaming,” says Mr Dawes.

“We’re only just starting to learn how radically different the internal worlds of those without imagery are.”

Between 2 and 5 per cent of people have aphantasia, but most of us assume visual imagery is something everyone has, says Mr Dawes. Photo: Unsplash.

While people with aphantasia wouldn’t have been able to picture the image of the sunset mentioned above, many could have imagined the feeling of sand between their toes, or the sound of the seagulls and the waves crashing in.

However, 26 per cent of aphantasic study participants reported a broader lack of multi-sensory imagery – including imagining sound, touch, motion, taste, smell and emotion.

“This is the first scientific data we have showing that potential subtypes of aphantasia exist,” says Professor Joel Pearson, senior author on the paper and Director of UNSW Science’s Future Minds Lab.

Interestingly, spatial imagery – the ability to imagine distance or locational relationship between things – was the only form of sensory imagery that had no significant changes across aphantasics and people who could visualise.

“The reported spatial abilities of aphantasics were on par with the control groups across many types of cognitive processes,” says Mr Dawes. “This included when imagining new scenes, during spatial memory or navigation, and even when dreaming.”

In action, spatial cognition could be playing Tetris and imagining how a certain shape would fit into the existing layout, or remembering how to navigate from A to B when driving.

What does having a ‘blind mind’ mean for the mental journeys we take every day when we imagine, remember, feel and dream? Photo: Unsplash.

While visualising a sunset is a voluntary action, involuntary forms of cognition – like dreaming – were also found to occur less in people with aphantasia.

“Aphantasics reported dreaming less often, and the dreams they do report seem to be less vivid and lower in sensory detail,” says Prof Pearson.

“This suggests that any cognitive function involving a sensory visual component – be it voluntary or involuntary – is likely to be reduced in aphantasia.”

Aphantasic individuals also experienced less vivid memories of their past and reported a significantly lower ability to remember past life events in general.

“Our work is the first to show that aphantasic individuals also show a reduced ability to remember the past and prospect into the future,” says Mr Dawes. “This suggests that visual imagery might play a key role in memory processes.”

While up to one million Australians could have aphantasia, relatively little is known about it – to date, there have been less than 10 scientific studies on the condition.

More research is needed to deepen our understanding of aphantasia and how it impacts the daily lives of those who experience it.

“If you are one of the million Australians with aphantasia, what do you do when your yoga teacher asks you are asked to ‘visualise a white light’ during a meditation practice?” asks Mr Dawes.

“How do you reminisce on your last birthday, or imagine yourself relaxing on a tropical beach while you’re riding the train home? What’s it like to dream at night without mental images, and how do you ‘count’ sheep before you fall asleep?”

The researchers note that while this study is exciting for its scope and comparatively large sample size, it is based on participants’ self-reports, which are subjective by nature.

Next, they plan to build on the study by using measurements that can be tested objectively, like analysing and quantifying people’s memories.

To be involved in this type of research and learn more about aphantasia and the Future Minds Lab, visit https://www.futuremindslab.com/aphantasia.

I-LIKE-NAPS on June 29th, 2020 at 01:32 UTC »

I'm an aphant, not just visual imagery but all senses blind. I don't even "hear" my own inner monologue. I find the research on aphantasia, as scant as it is, fascinating. For many years I didn't know I was different, but so much now makes sense. The knowledge helps me understand the perspective of those who aren't aphants, not be so hard on myself for having a lackluster memory, and advocate for myself in teachable moments, such as when I am asked to visualize something, which I now know is not a metaphor for "think about" or "keep a mental list of the stuff I'm about to say".

Funny story. My mom is an artist. When I was young I asked her to show me how to paint. At the time, when she talked about looking at the subject and then "seeing" the image of the subject on the canvas, I thought she meant that you stare at the subject for a long time so when you look at the white canvas, you can trace the lines of the negative afterimage that was burned into your eyeballs... and then do that over and over. It seemed so tedious.

diszt on June 28th, 2020 at 22:09 UTC »

I have a terrible visual imagination, but if I focus very hard I can see flashes of an image, or a more detailed small section of an image (usually unable to control which section I see). If I focus hard on maintaining the flash of an image I see, it melts or morphs or deforms in some way, and either becomes another image, or more frequently dissolves into yellowy/greeny pulsing shapes that come in sorts of patterns that I find difficult to describe.

Wagamaga on June 28th, 2020 at 19:31 UTC »

Picture the sun setting over the ocean.

It’s large above the horizon, spreading an orange-pink glow across the sky. Seagulls are flying overhead and your toes are in the sand.

Many people will have been able to picture the sunset clearly and vividly – almost like seeing the real thing. For others, the image would have been vague and fleeting, but still there.

If your mind was completely blank and you couldn’t visualise anything at all, then you might be one of the 2-5 per cent of people who have aphantasia, a condition that involves a lack of all mental visual imagery.

“Aphantasia challenges some of our most basic assumptions about the human mind,” says Mr Alexei Dawes, PhD Candidate in the UNSW School of Psychology.

“Most of us assume visual imagery is something everyone has, something fundamental to the way we see and move through the world. But what does having a ‘blind mind’ mean for the mental journeys we take every day when we imagine, remember, feel and dream?”

Mr Dawes was the lead author on a new aphantasia study, published overnight in Scientific Reports. It surveyed over 250 people who self-identified as having aphantasia, making it one of the largest studies on aphantasia yet.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-65705-7