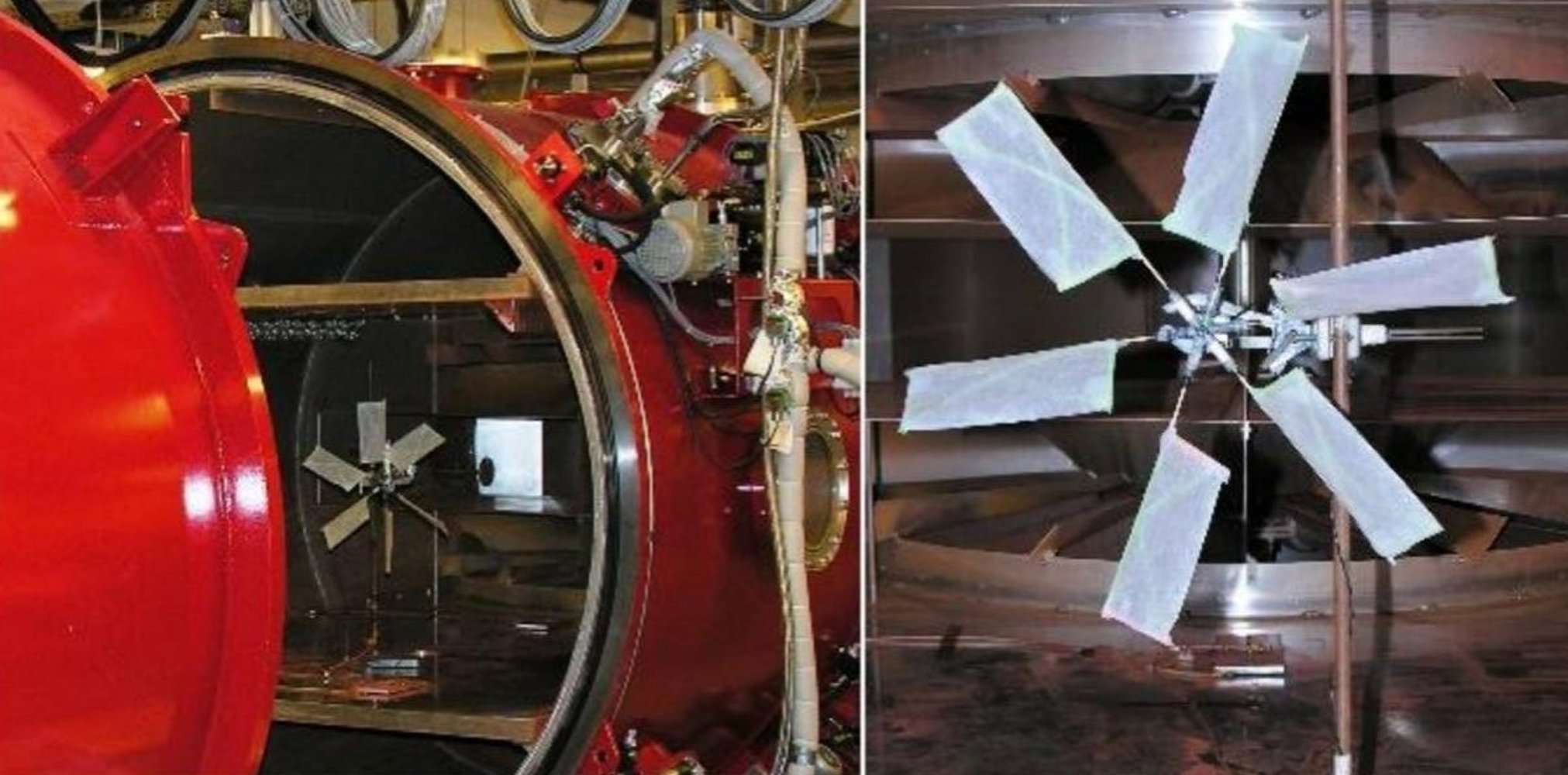

The Aarhus Wind Tunnel Simulator II at Aarhus University in Denmark. Left: The wind turbine positioned in the wind tunnel, which is 6.5 feet (2 meters) wide. Right: Close-up of the wind turbine, with the wind tunnel fan visible in the background.

Wind power on Mars is feasible, a new study suggests.

Researchers demonstrated a small, lightweight wind turbine under simulated Martian atmospheric conditions, at the Aarhus Wind Tunnel Simulator II at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Those trials were held in the fall of 2010. The study team reported follow-up findings, and a strong take-home message, in a paper presented at the Mars Workshop on Amazonian and Present Day Climate, which was held last week in Lakewood, Colorado. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

"For now, we can say for the first time and with certainty, that, YES, you can use wind power on Mars!" the researchers, led by Christina Holstein-Rathlou of Boston University's Center for Space Physics, wrote in the study.

No planet is more steeped in myth and misconception than Mars. This quiz will reveal how much you really know about some of the goofiest claims about the red planet. Start the Quiz 0 of 10 questions complete

Mars Myths & Misconceptions: Quiz No planet is more steeped in myth and misconception than Mars. This quiz will reveal how much you really know about some of the goofiest claims about the red planet. 0 of questions complete

The objective of the wind turbine investigations was to see how much power is produced under realistic Martian atmospheric conditions.

Standard power sources wouldn't work well for future possible robotic missions to the polar regions of Mars, Holstein-Rathlou and her colleagues noted. Solar cells would have limited or no sunlight for roughly half the year, and the heat expunged by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (the device that powers NASA's Curiosity Mars rover and many other deep-space explorers) or similar devices would be detrimental to any science performed in a polar region.

A different possible power source is a wind turbine along with a battery for storing produced electricity, potentially in combination with solar cells, the researchers said.

In this artist's illustration, NASA's Phoenix Mars Lander begins to shut down operations as winter sets in. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

The concept of a Martian wind turbine has been explored theoretically in connection with human missions to the Red Planet. For example, a 100-kilowatt wind turbine was designed and tested in Antarctica — a general Mars analog site — by researchers from NASA's Ames Research Center in California.

However, these early concepts were large and heavy and would require substantial wind speeds to be functional, Holstein-Rathlou and her colleagues said. Also, these sizes and masses are unfeasible for science missions to Mars, which are generally relatively small and lightweight, the researchers added.

The 2010 wind-tunnel experiments were run at six different wind speeds. These were based on the most common wind speeds at the far northern landing site of NASA's Phoenix Mars lander, which touched down in May 2008; the minimum wind speed needed to make the wind turbine rotate; and the maximum wind speed the wings could withstand. (Typical wind speeds on Mars are roughly 4.5 mph to 22 mph, or 7 to 35 km/h.)

For each wind speed, the output voltage was measured for 30-120 seconds.

"The optimal locations for this type of power production are areas where the sun doesn't always shine, but winds will blow, such as latitudes poleward of the polar circles," the researchers wrote.

A suite of studies still need to be performed before turbine-toting probes are ready to launch toward Mars, the team stressed. However, most designs, singular or part of a system, would be more efficient than the setup tested in the 2010 experiments, and thus should lead to power production in a range that is able to support some or all instrumentation on a small lander, the researchers said.

Leonard David is author of "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet," published by National Geographic. The book is a companion to the National Geographic Channel series "Mars." A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. This version of the story published on Space.com.

SirJelly on June 28th, 2018 at 15:12 UTC »

This thread is full of myths and misinformation:

1) Mars dust storms do not produce hurricane force winds such as those portrayed in the Martian movie.

2) Mars's atmosphere is not very dense which means a 60mph wind on mars does not exert nearly as much force as a 60mph wind on earth does.

Mars's atmospheric density = 0.02 kg/m3 Earth's atmospheric density = 1.2 kg/m33) Both wind and solar are much less efficient on Mars than they are on Earth.

4) Wind power's principle value on mars is imagined to be for use during storms when winds are highest, but dust dramatically lowers the power output of solar. They are compliments not substitutes. These storms are usually seasonal and moderately predictable.

5) Solar panel manufacturing requires a lot of high tech manufacturing processes compared to rudimentary wind turbines, so a significant portion of winds value may come from the ability to be constructed from materials gathered on the planet, rather than hauling giant slices of silicon crystals across the solar system.

6) One alternative, Radioisotope Thermoelectric generators (RTGs) are not dangerous to be around, pose zero risk of explosion, and are not exceptionally heavy. The nuclear fuels used decay almost entirely alpha radiation, the thin metal walls of the container are sufficient to keep the material safe to be around, you just don't want to eat it. They need to dump waste heat to work, and the authors seem to think this is problematic. (Mars is pretty cold however, last i'd done any math on it, RTGs waste heat would actually be very useful for climate control. maybe the authors are weighing something else more heavily). The fuel doesn't last long, with power output decreasing dramatically over 10 years and would need to be resupplied from earth.

EDIT:

7) It takes an incredible amount of energy to spin up even the most rudimentary nuclear operations needed to refine fuel. The volume of mining material to be processed to get enough for a single nuclear reactor is immense. It truly takes a nations worth of infrastructure to provide all the resources to refine nuclear fuel. If we go the nuclear option, we will be sending all the machinery and material from Earth, and while it is very heavy and expensive to launch, it's probably the only option to support a colony of thousands.

nono_baddog on June 28th, 2018 at 14:06 UTC »

Yeah in the game Surviving Mars you can use solar or wind power (to start). Gotta keep those solar cells clean though

jackthomasgrant on June 28th, 2018 at 13:58 UTC »

What’re the benefits of wind over solar on Mars?