March 20th marked the birthday of Fred Rogers, an ordained Presbyterian minister who is best remembered for his pioneering work in children’s television as Mister Rogers of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Rogers, who passed away from stomach cancer in 2003, was the first to acknowledge that the success of his Neighborhood was not his alone, but the result of those whose shared it with him: a chef who walks with a limp, a handyman with a penchant for jazz, a speedy courier who talks as fast as he delivers, and yes, even an operatic police officer.

When Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood first aired in 1968 on a public television station in Rogers’ native Pittsburgh, American viewers were desperate for some good news. The previous decade had brought political assassinations, the threat of the Cold War, the Sexual Revolution, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Vietnam War; and television had delivered all of it right into America’s dens and sitting rooms. With this new technology, no place was safe from chaos and turmoil. No place was simply “over there”—every place was near; every threat, local; every conflict, personal. In many ways, television shaped and escalated the conflicts of the 1960s the same way that the internet shapes and escalates current ones, simultaneously expanding and shrinking our sense of community.

We see two men humbling themselves. We see two men cleansing each other through acts of communion and identification. We see two men showing the world how reconciliation happens.

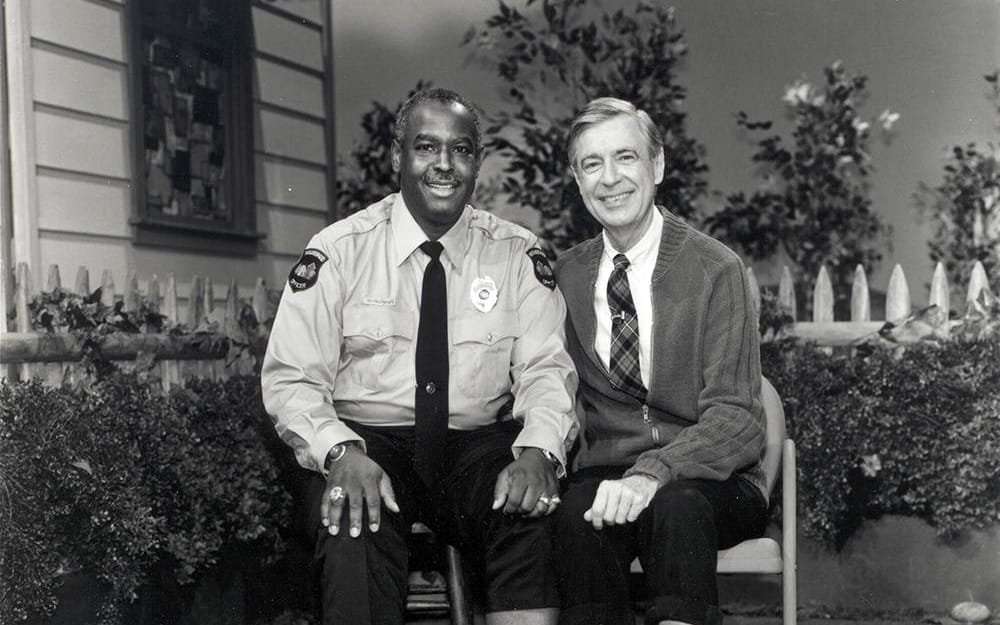

Over the course of thirty-one years and 865 episodes, Rogers would use his Neighborhood to show the world as it should be—a microcosm of kindness where neighbors love and support each other through difficult times of death, divorce, and danger. It was also a space where Rogers helped viewers confront their own fear and prejudices, leading them past them in his own non-threatening way. From the beginning, Rogers specifically challenged the nation’s understanding of race through his friendship—both on and off-screen—with Francois Clemmons, the Neighborhood police officer who just happened to be an African-American.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Francois Clemmons was the descendent of slaves and sharecroppers; but like many other blacks, his family moved north to the industrial mid-west and he grew up in Youngstown, Ohio. Clemmons remained deeply connected to his roots, though, both through the spirituals that his mother taught him and by cultivating his natural vocal talent in the church. Eventually, Clemmons pursued a career as an opera singer and was already touring when Rogers heard him perform at his home church in Pittsburgh. Soon after hearing him, Rogers invited Clemmons to appear in the Neighborhood—as a police officer.

“Fred came to me,” Clemmons recounts in a recent StoryCorps interview, “and said, ‘I have this idea…you could be a police officer.’ That kind of stopped me in my tracks. I grew up in the ghetto. I did not have a positive opinion of police officers. Policeman were sicking police dogs and water hoses on people. And I really had a hard time putting myself in that role. So I was not excited about being Officer Clemmons at all.”

But Rogers prevailed and Clemmons joined MRN in August 1968, only four months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In doing so, Clemmons became the first African-American with a recurring role on a children’s television series. But as progressive as this was, Rogers decided to press social convention even further.

Episode 1065, which aired only a few months after Clemmons’ debut, opens in the typical manner with Rogers inviting viewers to be his neighbor; but instead of putting on his iconic cardigan, Rogers talks about how hot the day is and how nice it would be to put his feet in a pool of cold water. He moves to his front yard where he fills a small plastic pool with water and begins to soak his feet. Soon Officer Clemmons drops by for a visit and Mr. Rogers invites him to share the pool with him. Clemmons quickly accepts, rolls up his pant legs of his uniform, and places his very brown feet in the same water as Rogers’ very white feet.

Today, this small gesture may seem insignificant, but in 1969, it was considerable. Like public fountains, public transportation, and public schools, the public pool had become a battleground of racial segregation. Under Jim Crow era policy, not only could black and whites not swim at the same time, many pools were entirely off limits to blacks, fueled by a fear that African-Americans carried disease and the view that swimming pools were physically (and by extension sexually) intimate contexts. Like the lunch counter and public buses, swimming pools became a point of protest. Both black and white protestors staged wade-ins and swim-ins at beaches and community pools; but just like at sit-ins, local authorities responded with arrest and sometimes, physical violence. One iconic image from June 1964 shows a hotel manager dumping muriatic acid in a pool of black and white bathers, while a young black woman clings to a white man screaming in terror.

But here in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, only five years later, a quiet Presbyterian minister and an African-American police officer show the world how to integrate swimming pools. Rogers invites; Clemmons accepts. As Clemmons slips his feet into the pool, the camera holds the shot for several seconds, as if to make the point clear: a pair of brown feet and a pair of white feet can share a swimming pool. Nearly 25 years later Rogers and Clemmons reenacted this moment. A much older Rogers and Clemmons sit with their feet in a similar blue wading pool talking about the many different ways that children and adults say “I Love You”–from singing to cleaning up a room to drawing special pictures to making plays. As the scene ends, Rogers takes a towel and helps Clemmons dry his feet with a simple, “Here, let me help you.”

This year Mr. Rogers’ birthday fell on Palm Sunday, the first day of Holy Week in which Christians commemorate the final days of Jesus’ earthly ministry. Holy Week observances involve fasting, special services, and seasonal rites, including the rite of foot washing. For some churches, foot washing is a weekly or monthly ordinance, but for many others, foot washing happens only on Maundy Thursday, the day of Holy Week that commemorates the Last Supper.

The rite itself comes from the account in the Gospel of John that records Jesus girding himself with a towel and washing his disciples’ feet. After he finished, he sat down and said to them,

If I, then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example, that you should do as I have done to you. Truly, truly, I say to you, a servant is not greater than his master; nor is a messenger greater than the one who sent him.

The “Maundy” of Maundy Thursday comes from the Latin word mandatum or “command,” referring to Jesus’ commanding his disciples to practice the same love and service toward each other that he had shown them.

But foot washing is more than an act of humility and service. In many ways, it is also an act of cleansing and repentance. Throughout the Scripture, washing and water symbolize the purification from sin and disease—from the ceremonial washing of the Old Testament to Naaman’s washing in the Jordan to the rite of baptism. Even within the context of the Last Supper, Jesus was washing his disciples’ feet of the grime that had accumulated from walking the dusty roads of Jerusalem. And when Peter objected to Jesus’ act of humility, Jesus warns him that “If I do not wash you, you have no share with me.”

Perhaps this image of Jesus as the servant-cleanser was in the Apostle Paul’s mind when he describes the servanthood of Jesus in Philippians 2:

Have this mind in you which was also in Christ Jesus… who made himself nothing, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being fount in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even the death of the cross.

In many ways, the servanthood of Jesus cannot be separated from the cleansing and redemption that comes through the Incarnation and Crucifixion.

It’s no surprise, then, that when a Presbyterian minister wanted to heal the divide between blacks and whites, to show us how to serve each other, it looked very much like Jesus’ own servanthood. When Rogers asked Clemmons to become a police officer, he asked him to become the enemy in order to redeem the enemy—just as Jesus took on the form of his enemy to redeem us. And when Rogers shared his pool and wiped his friend’s feet with a towel, he was repenting through servanthood—the same servanthood that motivated Jesus to take up the towel the night before his death.

But both acts required humility. Both acts required relinquishing privilege—the privilege of anger on Clemmons’ part and the privilege of comfort on Rogers’ part. And through this humility, both men embody Christ: neither condescending to the other; both simply surrendering to the other. So that in the very same act, the humiliated are brought up and the proud are brought down.

In one brief scene on a children’s television show, we see this happen. We see two men humbling themselves. We see two men cleansing each other through acts of communion and identification. We see two men showing the world how reconciliation happens. And we hear Mr. Rogers say, in his own quiet voice, “Sometimes just a minute like this will really make a difference.”

MrsMcFeely5 on June 21st, 2018 at 12:53 UTC »

Mr. Rogers was a beautiful person. If I do a tiny fraction of he good he did in my life, I will be very satisfied.

OMGLMAOWTF_com on June 21st, 2018 at 11:33 UTC »

If you like this TIL, you’ll probably like the Mr. Rogers documentary that’s out now.

https://m.imdb.com/title/tt7681902/

TheRealR2D2 on June 21st, 2018 at 11:28 UTC »

Good TIL, made me warm inside, thank you. Rogers was an amazing man and continues to surprise me.