Roughly 60 years after the abolition of slavery, anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston made an incredible connection: She located the last surviving captive of the last slave ship to bring Africans to the United States.

Hurston, a known figure of the Harlem Renaissance who would later write the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, conducted interviews with the survivor but struggled to publish them as a book in the early 1930s. In fact, they are only now being released to the public in a book called Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” that comes out on May 8, 2018.

Author Zora Neale Hurston (1903-1960). (Credit: Corbis/Getty Images)

Hurston’s book tells the story of Cudjo Lewis, who was born in what is now the West African country of Benin. Originally named Kossula, he was only 19 years old when members of the neighboring Dahomian tribe captured him and took him to the coast. There, he and about 120 others were sold into slavery and crammed onto the Clotilda, the last slave ship to reach the continental United States.

The Clotilda brought its captives to Alabama in 1860, just a year before the outbreak of the Civil War. Even though slavery was legal at that time in the U.S., the international slave trade was not, and hadn’t been for over 50 years. Along with many European nations, the U.S. had outlawed the practice in 1807, but Lewis’ journey is an example of how slave traders went around the law to continue bringing over human cargo.

To avoid detection, Lewis’ captors snuck him and the other survivors into Alabama at night and made them hide in a swamp for several days. To hide the evidence of their crime, the 86-foot sailboat was then set ablaze on the banks of the Mobile-Tensaw Delta (its remains may have been uncovered in January 2018).

Most poignantly, Lewis’ narrative provides a first-hand account of the disorienting trauma of slavery. After being abducted from his home, Lewis was forced onto a ship with strangers. The abductees spent several months together during the treacherous passage to the United States, but were then separated in Alabama to go to different plantations.

A marker to commemorate Cudjo Lewis, considered to be the last surviving victim of the Atlantic slave trade between Africa and the United States, in Mobile, Alabama. (Credit: Womump/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

“We very sorry to be parted from one ’nother,” Lewis told Hurston. “We seventy days cross de water from de Affica soil, and now dey part us from one ’nother. Derefore we cry. Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama.”

Lewis also describes what it was like to arrive on a plantation where no one spoke his language, and could explain to him where he was or what was going on. “We doan know why we be bring ’way from our country to work lak dis,” he told Hurston. “Everybody lookee at us strange. We want to talk wid de udder colored folkses but dey doan know whut we say.”

As for the Civil War, Lewis said he wasn’t aware of it when it first started. But part-way through, he began to hear that the North had started a war to free enslaved people like him. A few days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered in April 1865, Lewis says that a group of Union soldiers stopped by a boat on which he and other enslaved people were working and told them they were free.

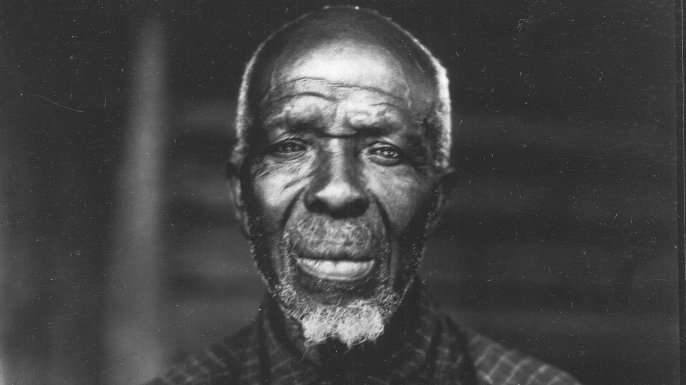

Cudjo Lewis at home. (Credit: Erik Overbey Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama)

Lewis expected to receive compensation for being kidnapped and forced into slavery, and was angry to discover that emancipation didn’t come with the promise of “forty acres and a mule,” or any other kind of reparations. Frustrated by the refusal of the government to provide him with land to live on after stealing him away from his homeland, he and a group of 31 other freepeople saved up money to buy land near the state capital of Mobile, which they called Africatown.

Hurston’s use of vernacular dialogue in both her novels and her anthropological interviews was often controversial, as some black American thinkers at the time argued that this played to black caricatures in the minds of white people. Hurston disagreed, and refused to change Lewis’ dialect—which was one of the reasons a publisher turned her manuscript down back in the 1930s.

Many decades later, her principled stance means that modern readers will get to hear Lewis’ story the way that he told it.

salawm on May 11st, 2018 at 20:12 UTC »

Man, this line made me break down. "Our grief so heavy look lak we cain stand it. I think maybe I die in my sleep when I dream about my mama.” Ripped from his family at 19, never sees them again. That picture in his house shows a man who had to make the most bitter lemonade ever.

Papamato99 on May 11st, 2018 at 18:52 UTC »

I read a book about him and the ship he was on for a History class last semester. It was a really good read.

It's called Dreams of Africa in Alabama. I'd recommend it to anyone who enjoys history and wants a better understanding of the topic of slavery.

pipsdontsqueak on May 11st, 2018 at 18:32 UTC »

These kind of firsthand accounts are incredibly important and the preservation of vernacular offers a lot of insight into the lives of these individuals. Sometimes I think about how recent so much of American history is. A slave ship survivor told his story in the 20th century, after World War I, during the Great Depression. This man lived through two of the biggest wars America has been involved in, the Civil War and World War I, and told a personal account of being transported from Africa to be sold as a slave in the South.

I think there's often a disconnect when it comes to these periods of history, like we just jumped into the 20th century, but other people were most certainly alive to see both periods.

Edit: More excerpts from the interview in this Vulture article, courtesy of /u/lee61.

http://www.vulture.com/2018/04/zora-neale-hurston-barracoon-excerpt.html

The interviews were conducted over three months with a man named Cudjo Lewis, or Kossula, his original name, the last survivor of the last slave ship to land on American shores.