4 out of 4 stars Title The 15:17 to Paris Written by Dorothy Blyskal Directed by Clint Eastwood Starring Spencer Stone, Alex Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler Genre Drama Classification PG Country USA Language English Year 2018

Early in Clint Eastwood's The 15:17 To Paris, we glimpse the bedroom upholstery of a young Spencer Stone. For middle-school kids like Stone (and many fully matured adults), the tacked-up postering of the bedroom as sanctuary reveals something of adolescent aspiration. The kid who wants to be an astronaut lines his shelves with models of Apollo rockets and Mars rovers. The one who wants to be a palaeontologist (or a Spielbergean purveyor of blockbuster thrills) slumbers under Jurassic Park posters. The stocky Spencer Stone's shrine speaks to hopes of military heroism.

Besides an American flag, there are posters for Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket, and the Second World War-era Pacific Theatre epic Letters from Iwo Jima. That Iwo Jima was, like The 15:17 To Paris, directed and produced by Eastwood is meant as more than a wink-nudge in-joke. (And ditto the Eastwood T-shirt worn by fellow military hopeful Alek Skarlatos.) It's not just that Eastwood's movies are entrenched in the cultural firmament (see also: the Gran Torino poster Tom Hanks jogs past in 2016's Sully). It's that his movies are now in conversation with one another. This dialogue between Eastwood's own iconography, and that of the military and America and the very notion of heroism, is precisely what makes The 15:17 To Paris a consummate work in Eastwood's filmography.

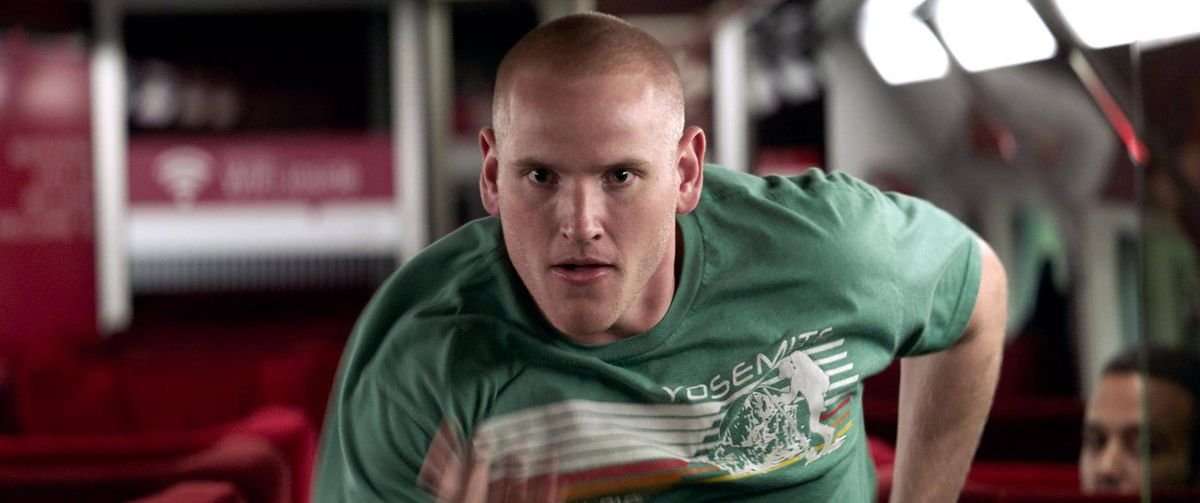

Admittedly, the elevator pitch for 15:17 smacks of a certain tackiness. Here is a film about three Americans (and, lest we forget, a Brit and a Frenchman) who successfully disarmed an attacker aboard a high-speed train between Amsterdam and Paris in 2015. The film casts the actual American kids – the "real heroes," as they're billed in promotion material – as themselves.

As a gimmick, it's not without precedent. Werner Herzog's Little Dieter Needs to Fly saw German-American fighter pilot Dieter Dengler reenacting his imprisonment and escape from a North Vietnamese POW camp. In 1955, heavily decorated WWII veteran Audie Murphy played himself in To Hell and Back. Even Eastwood's last military romp, 2014's American Sniper, cast Navy SEAL Kevin Lacz as himself, playing opposite Bradley Cooper's Chris Kyle. The conceit itself is not exactly revolutionary. Eastwood's execution is.

The 15:17 to Paris sees Eastwood, 87, course-correcting in real time. Where American Sniper took flack in some quarters for its fast-and-loose interpretation of the U.S. military's deadliest sharpshooter, 15:17 responds by casting the actual guys. Stone, Skarlatos and Anthony Sadler reenact not only their takedown of a lone gunman aboard a passenger train, but their freewheeling backpacking trip across several European capitals. (The invitation to imagine a scowling Eastwood blocking out a bump-and-grind club scene in an Amsterdam nightclub offers more genuine entertainment than most Hollywood pictures dumped in cinemas during this, or any, season.) Throughout the film, Sadler's character (who is Sadler himself) compulsively stops to pose for "selfies." And this is very much what 15:17 is: an immersive, 3-D-rendered selfie, which arrests real-world historical figures in the glistening amber of cinema.

This preoccupation with simulation was also apparent in Sully, in which Hanks's real-world airline pilot Sully Sullenberger must defend the legitimacy of his professional choices against competing evidence compiled by computer run-throughs reenacting those choices. In so doing, that film posed compelling questions about the difference between real historical personas and their on-screen (or in-box, digitized) avatars. With 15:17, Eastwood gamely attempts to dissolve the distinction altogether. In so doing, he turns the trio into genuine (pardon the pun) historical actors.

As the friends gallivant from Rome to Venice to Berlin and then fatefully from Amsterdam to Paris, Stone is seized by a looming sense of predestination. "Ever feel like life is catapulting you toward something?" he asks Sadler, as they drink in a Venetian sunset. Eastwood stakes out a middle ground here between the tired notion that history is made by great men (or women), and the more despondently fatalistic idea that all events are determined by the grand motion of social and economic forces, in which the individual is incidental if not entirely irrelevant. Through its seductive back-and-forth editing rhythm between the events of the train attack and those leading irrevocably toward it, Eastwood offers the clearest version yet of his vision of human affairs: History may chug ever forward, locomotive-like, but there are engineers driving it.

This may all seem awfully grand. And I'm sure the suggestion that Eastwood is some sly dialectical materialist may strike some as cloying, if not insincere. But The 15:17 To Paris thinks through issues of heroism and history with remarkable intelligence and clarity. And its ostensible demerits – the hammy-seeming performances of its stars and the supporting cast of sitcom actors (Judy Greer, Jenna Fischer, Thomas Lennon, Tony Hale), the air of American triumphalism – all work in service of these ideas. As to the tedious business of "defending" Eastwood's ostensible political bent: that's another matter altogether, and one which is fundamentally irrelevant to his film's formal and theoretical invention.

In his landmark essay on late-career style, Edward Said noted that an artist's final-years work is generally seen as an attempt to establish a sense of "harmony and resolution" with an existent canon. "But what," Said wonders, "of artistic lateness not as harmony and resolution, but as intransigence, difficulty and contradiction?" The 15:17 To Paris, like Sully, American Sniper and (to a lesser extent) Gran Torino before it, combines such conceptions of late style: both harmonious and intransigent, resolute and difficult, defined by lively contradiction.

Unlike the silhouettes of the sundry gunslingers he played for decades, Clint Eastwood is an American artist who refuses to watch the sun set on him, preferring instead to rage, with wild intelligence and a bit of boiling contempt, against the dying of the light.

The 15:17 to Paris opens Feb. 9

Brave_Frenchman on February 9th, 2018 at 01:35 UTC »

Imagine watching this and then watching Letters from Iwo Jima right after.

meshan on February 8th, 2018 at 23:10 UTC »

Do the terrorists play themselves?

YaBoyStevieJay on February 8th, 2018 at 22:51 UTC »

I feel like if you're gonna make a movie starring a bunch of non-actors, you probably shouldn't hire Clint "let's do it in two takes and go home" Eastwood as the director.