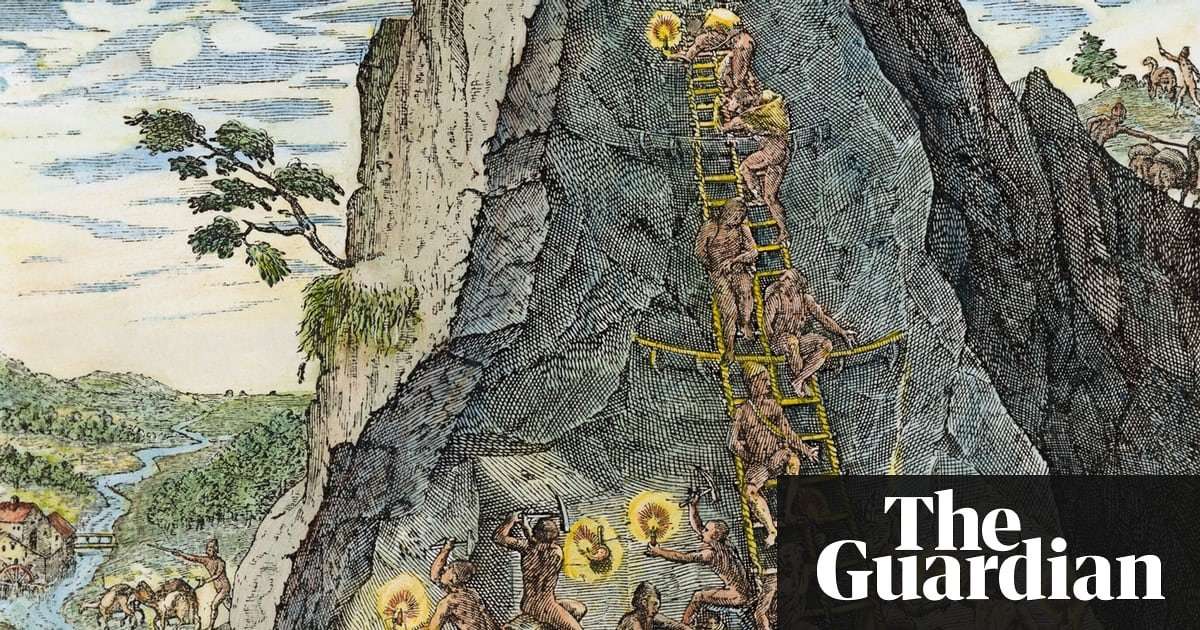

Spain After 400 years lost, 'cursed' novel of Spain's imperial age is finally published Previous workers on Golden Age manuscript The Orphan’s Story died, leading to rumours of curse Mining in Potosi, Bolivia. Photograph: Granger/REX/Shutterstock

Four hundred years after it was written, a lost and supposedly cursed Golden Age novel chronicling the splendour, adventure and violence of Spain’s imperial zenith has been published for the first time.

Historia del Huérfano, or The Orphan’s Story, charts the progress of a 14-year-old Spaniard who leaves Granada and heads to the Americas to seek his fortune. Its hero ricochets around the Spanish empire, from the high-society fiestas of Lima to the mephitic mines of Potosí, and goes on to witness Sir Francis Drake’s attack on Puerto Rico and the sacking of Cádiz.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Sir Francis Drake in the harbour of Cádiz. Photograph: Images Group/REX/Shutterstock

After romantic escapades and the odd shipwreck and run-in with pirates, the soldier-cum-missionary finally manages to embrace the calm of monastic life in the capital of viceregal Peru.

“There’s an awful lot of travelling, but you do get a sense of what the viceroyalty of Peru was like from the inside and of the exchange of people and goods between Europe and America,” said Belinda Palacios, a Peruvian academic who spent two years editing the book back to life.

The story was written between 1608 and 1615 by Martín de León y Cárdenas, a Spanish Augustinian friar born near Malaga in 1584 and who, like his eponymous hero, had travelled to Lima.

It was set to appear in 1621 under the nom de plume of Andrés de León, but it never made it to the printing presses – perhaps because its author feared it might cause him problems as he embarked on an ecclesiastical career that would see him become an archbishop, and the president and captain-general of the viceroyalty of Sicily.

A Spanish academic rediscovered the manuscript in the archives of the Hispanic Society of America in 1965. Previous attempts to publish The Orphan’s Story had come to nothing, giving rise to rumours that something malevolent lurked among its 328 pages.

“When I started working on it, a lot of people told me that the book was cursed and that people who start working on it die,” Palacios said.

“I laughed it off but I was a bit apprehensive at the same time. It’s taken a while because the people who have worked on it have died – one from a strange disease, one in a car accident and another of something else.”

Palacios hopes the curse has been lifted after it was recently published by the José Antonio de Castro Foundation, which works to safeguard Spain’s literary heritage.

She says the book’s blend of fiction, autobiography and historical documents – Martín de León used a letter from one of the generals who fought Drake in Puerto Rico – offers a richly detailed, contemporary portrait of the author’s world.

“It also gives us a nuanced view of the story of the conquest. People always go on about the big evil Spaniards coming and what they did to the indigenous people, but when you read this, you see there was a spirit of adventure that drove people. It wasn’t ‘let’s go over there, crush the indians and rob them’. It was more like a big business, in which adventure and discovery played a part.”

Beyond the descriptions of Lima’s poets, parties and bullfights, the text also affords glimpses of the slave labour that fuelled the celebrations and the empire itself.

On a visit to the mercury mines at Huancavelica, the Orphan sees 800 indigenous workers toiling in a hot, humid, fetid place of “great dangers, risks, darknesses, hazards and caverns”. The mine is described as “scene from hell or from the mythical forges of Vulcan’s cyclopses”.

Martín de León acknowledges the horrific realities of the mines and bemoans the corruption and chaos of Potosí, but he is very much a man of his time. Unlike his celebrated Dominican forerunner, Bartolomé de las Casas, he was no pioneering advocate of indigenous rights.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Mount Potosi, Bolivia. Photograph: Images Group/REX/Shutterstock

“He recognises that the indigenous people are being mistreated and exploited and that life is hard for them,” Palacios said. “But what Martín de León is criticising isn’t the fact that the indigenous people are being exploited so white people don’t have to do the work, which is the modern take. He’s criticising the fact that the indigenous population is being exploited to the point of disappearance.”

The treatment of the indigenous people was, for him, a short-sighted act of Spanish self-sabotage.

“I get the feeling that he’s saying the system must change because we’re wiping out the local populations and that’s not going to be viable in the long term,” Palacios said. “Yes, there’s a criticism there, but we shouldn’t see him as another Bartolomé de Las Casas, fighting to defend the Indians. That’s not there in the text.”

What she did find, however, were observations that still raise a smile centuries after Martín de León’s ink dried. She was amused by the narrator’s mockery of Italians for talking with their hands, and intrigued to read his complaints about the topical issue of judicial corruption in Peru.

Palacios likens reading the book to travelling back in time: “It’s a window on the past through which you can glimpse moments,” she said.

Despite the long months deciphering the friar’s handwriting, editing the book and correcting proofs, she says the project was painstaking but never dull.

“It was fun. I was back in the viceroyalty.”

rocketsjp on February 3rd, 2018 at 10:14 UTC »

that submission title is a novel in itself

nodice05 on February 3rd, 2018 at 07:16 UTC »

Holy shit, MERCURY MINES? That's sounds terrible. What the hell were people in the 17th century using Mercury for?

TeevMeister on February 3rd, 2018 at 05:25 UTC »

Publishing a 400 year old, cursed novel? Sounds like a great plan, people will love it! Hey, let's use the printing company that my brother-in-law built on an old Indian burial ground. He'll give us a great deal!