An Ontario physicist is embarking on a NASA-funded expedition to Antarctica to collect meteorites, in hopes that the fallen space rocks will give researchers new insight into the outer reaches of the solar system.

Scott VanBommel, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Guelph, is joining the annual Antarctic Search for Meteorites for a six-week excursion to the Transantarctic Mountains, about 350 km from the South Pole.

It will mean sleeping in a two-person tent in one of the least hospitable environments on Earth, but VanBommel said it's a chance to give back to the scientific community.

"I'm just really happy to go and be a part of this important work," the 30-year-old said hours before his Friday departure. "We can learn a lot by studying these fragments of space rocks that potentially are in their native form, from when the solar system formed. They provide us little windows into the past, to study and potentially learn more."

Canadian physicist Scott VanBommel is one of a handful of volunteers selected from a pool of 100 researchers who apply each year to participate in the annual trip. (University of Guelph/Canadian Press)

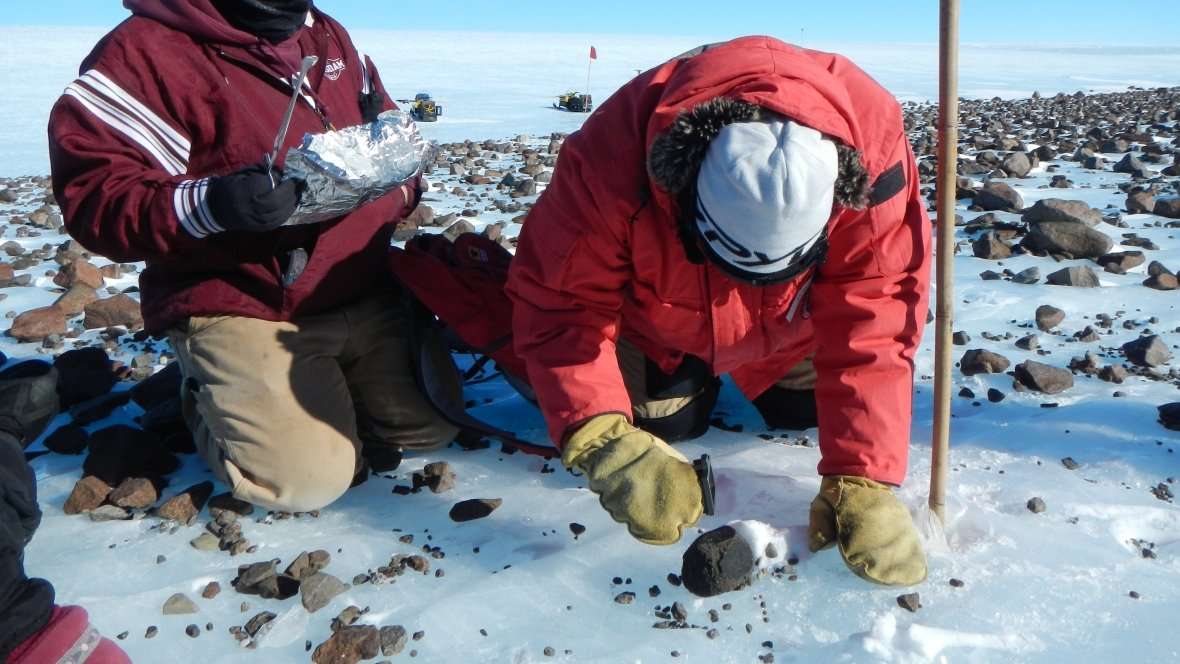

Antarctica's empty, ice-covered expanse makes the continent ideal for spotting space debris.

"Meteorites fall pretty uniformly all over the world, but what makes Antarctica special is that you have this white backdrop, so you have these dark meteorites and this light background," VanBommel said. "It makes them much easier to find than, say, around here where you have weathering and erosion and dirt."

Antarctica is also home to giant ice sheets which, over thousands of years, gradually shift toward the edges of the continent. When the ice sheets run up against mountain ranges or other natural barriers, old ice deep below the surface gets forced up, bringing deposits of old meteorites with it.

Led by Ralph Harvey, a planetary materials professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, the expedition team will split into two groups of four people.

One group will continue the ongoing systemic search of an area visited in previous missions.

The second group, which includes VanBommel, will conduct "spot-to-spot" reconnaissance, looking for new sites.

"It'll be exciting," VanBommel said. "We're covering a lot of ground this year."

The Norwich, Ont., native is one of a handful of volunteers selected from a pool of 100 researchers who apply each year to participate in the trip.

In 2013, scientists discovered an 18-kilogram meteorite in eastern Antarctica, the largest in the area since 1988. 425 meteorites were found during the 40-day expedition. (International Polar Foundation)

As one of the rookie members of the team, VanBommel went through a three-day boot camp at Case Western to prepare him for the trip.

"We went over all the details of what we'll be doing, the type of equipment we'll have, safety stuff. It was very thorough three days," he said.

Since 1976, the Antarctic Search for Meteorites has brought back over 21,000 meteorite specimens. The samples they recover are shipped to a laboratory at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston. Samples of the meteorites are also sent to the Smithsonian Institution. Researchers from anywhere in the world can examine the meteorite samples, upon request.

PenguinScientist on November 25th, 2017 at 19:12 UTC »

I got to meet and listen to a lecture by one of the professors from Case Western who runs the NASA ASNMET program years ago during my undergraduate study. To this day, I regret not following up with him and joining the expedition that year. Had I gone, I'm sure my life would have continued in a completely different direction than it has now.

guested on November 25th, 2017 at 19:00 UTC »

The Canadians were probably just there on vacation, thought they'd pitch in to help out.

Lenny_Here on November 25th, 2017 at 17:52 UTC »

Potentially dumb question but why would a meterorite be ON TOP of the snow?