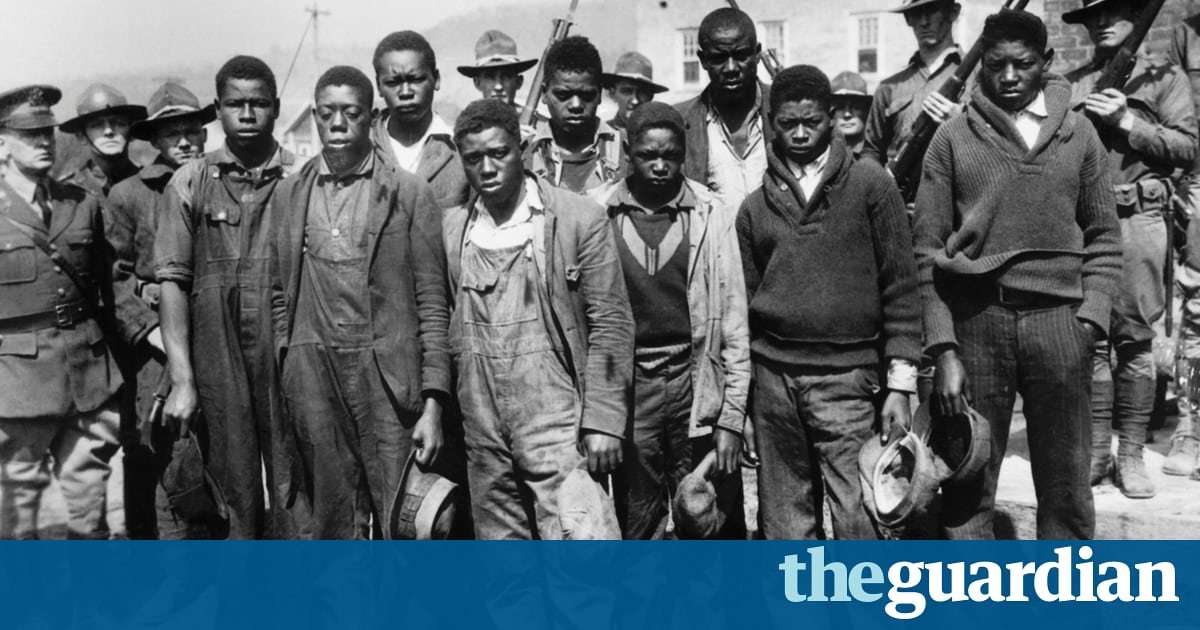

In 1919, a black soldier returned home to Blakely, Georgia, having survived the horrors of the first world war only to face the terrors of a white mob that awaited him in the Jim Crow-era south. When the soldier, William Little, refused to remove his army uniform, the savage mob exacted their punishment.

Little was just one of 3,959 African Americans who were brutally and often publicly killed across the southern states between the end of the Reconstruction era and the second world war, which is at least 700 more lynchings in these states than previously recorded, according to a report released on Tuesday by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). The authors’ inventory of the nearly 4,000 victims of what the report calls “terror lynchings” reveals a history of racial violence more extensive and more brutal than initially reported.

Many of the victims were, like Little, killed for minor transgressions against segregationist mores – or simply for demanding basic human rights or refusing to submit to unfair treatment. And though the names and faces of many who were lynched have slipped from the pages of history, their deaths, the report argues, have left an indelible mark on race relations in America.

“The trauma and anguish that lynchings and racial violence created in this country continues to haunt us and to contaminate race relations and our criminal justice system in too many places across the country,” it concluded.

The report, titled Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, is the result of nearly five years of investigation by EJI, a nonprofit organisation based in Montgomery, Alabama, into lynchings that occurred in 12 southern states between 1877 and 1950. It explores how the legacy of racial inequality in America was shaped and complicated by these violent decades, which saw thousands of African American men, women and children killed by “terror lynchings”, horrific acts of violence inflicted on racial minorities.

The sites of nearly all of these killings, however, remain unmarked in what the report calls an “astonishing absence of any effort to acknowledge, discuss or address” the violence that occurred. The authors make the case that the country cannot fully heal from this painful chapter of its history until it acknowledges the devastation that this era created and the residual effects of these acts.

Bryan Stevenson, the director of EJI, said the organization plans to erect monuments, memorials and markers in the communities where the lynchings took place, as a way of piercing the silence and starting a conversation.

Acknowledging the hardships he faces in getting the funding and approval to build the markers, not to mention the controversy that will almost certainly ensue, Stevenson said the process will force communities to reckon with the vicious history of racial violence.

“We want to change the visual landscape of this country so that when people move through these communities and live in these communities, that they’re mindful of this history,” Stevenson said. “We really want to see truth and reconciliation emerge, so that we can turn the page on race relations.”

He added: “We don’t think you should be able to come to these places without facing their histories.”

The report argues that atrocities carried out against African Americans during this period were akin to terrorism, and that lynchings were a tool to “enforce racial subordination and segregation”. It is the follow-up to the organisation’s 2013 report Slavery in America.

“It’s important to begin talking about it,” Stevenson said. “These lynchings were torturous and violent and extreme. They were sometimes attended by the entire white community. It was sometimes not enough to lynch the person who was the target, but it was necessary to terrorise the entire black community: burn down churches and attack black homes. I think that that kind of history really can’t be ignored.”

Stevenson said this era had a profound impact on contemporary issues facing African Americans.

“The failings of this era very much reflect what young people are now saying about police shootings,” Stevenson said. “It is about embracing this idea that ‘black lives matter’,” he added. “I also think that the lynching era created a narrative of racial difference, a presumption of guilt, a presumption of dangerousness that got assigned to African Americans in particular – and that’s the same presumption of guilt that burdens young kids living in urban areas who are sometimes menaced, threatened, or shot and killed by law enforcement officers.”

Absobloodylootely on November 3rd, 2017 at 04:01 UTC »

A bit on the side, but there was a serious attempt at introducing segregation when the US troops were based in the UK during WW2 too, with a significant back-lash from the Brits.

This write up about the Battle of Bamber Bridge (between white and black US troops - often described as the only ground battle in Great Britain during WW2) also references the tale that when the town was pressured to introduce segregation in the pubs they put up a sign in all the pubs saying "Black Troops Only". (edit to reflect it was all the pubs in town that did this)

bettinafairchild on November 3rd, 2017 at 02:55 UTC »

Yeah, whites hated seeing a black man in uniform. Especially if he was an officer or a non-commissioned officer. One of the most famous cases is of Isaac Woodard, a sergeant who was beaten and permanently blinded as he returned home after being discharged, while wearing his sergeant uniform.

KubrickIsMyCopilot on November 3rd, 2017 at 02:47 UTC »

Billie Holiday - Strange Fruit