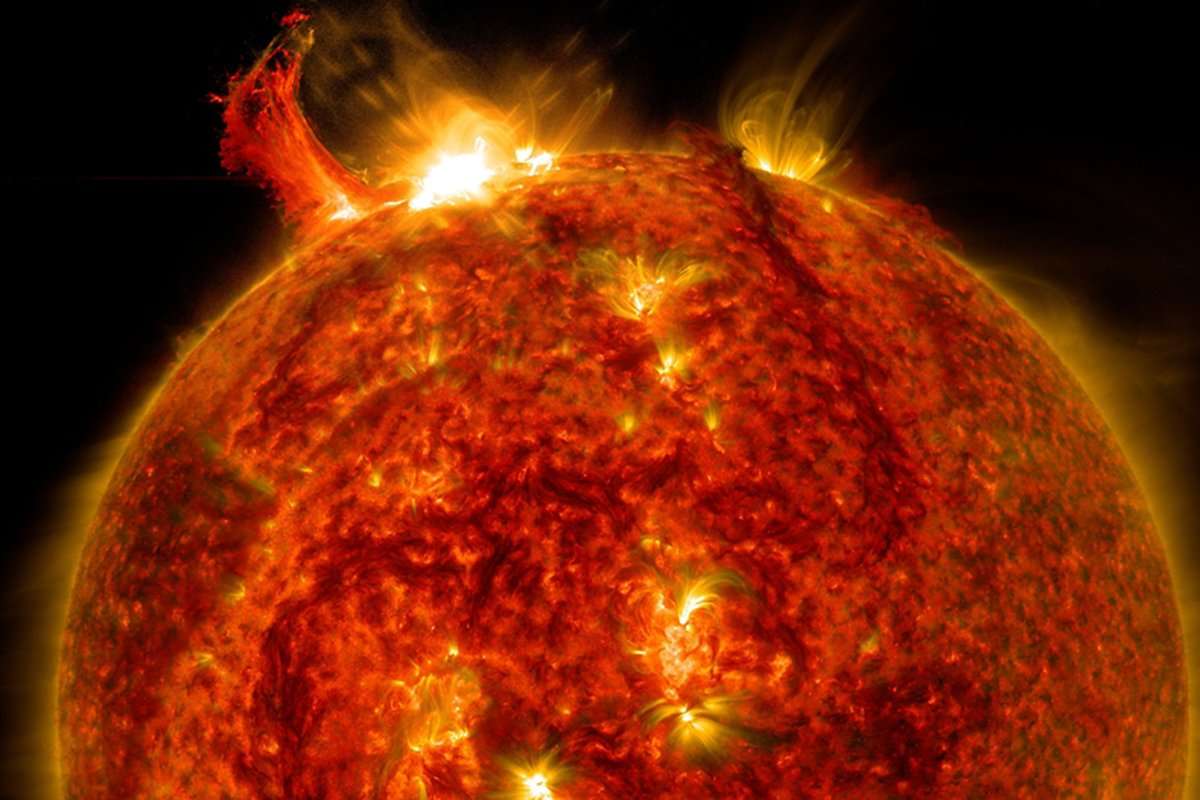

The sun could be one of our biggest threats in the next 100 years. If an enormous solar flare like the one that hit Earth 150 years ago struck us today, it could knock out our electrical grids, satellite communications and the internet. A new study finds that such an event is likely within the next century.

“The sun is usually thought of as a friend and the source of life, but it could also be the opposite,” says Avi Loeb at Harvard University. “It just depends on circumstances.”

Loeb and Manasvi Lingam, also at Harvard, examined data on other sun-like stars to see how likely solar “superflares” are and how they might affect us.

They found that the most extreme superflares are likely to occur on a star like our sun about every 20 million years. The worst of these energetic bursts of ultraviolet radiation and high-energy charged particles could destroy our ozone layer, cause DNA mutations and disrupt ecosystems.

But in the shorter term, the researchers say that less intense superflares of a type we know can happen on our sun could still cause problems. In 1859, a powerful solar storm sent enormous flares towards Earth in the first recorded event of its kind. Telegraph systems across the Western world failed, with some reports of operators receiving shocks from the huge amounts of electrical current forced through the wires.

“Back then, there was not very much technology so the damage was not very significant, but if it happened in the modern world, the damage could be trillions of dollars,” says Loeb. “A flare like that today could shut down all the power grids, all the computers, all the cooling systems on nuclear reactors. A lot of things could go bad.”

Loeb says an event as powerful as the 1859 one could cause about $10 trillion of damage to power grids, satellites and communications. A flare just a bit stronger could even damage the ozone layer.

Previous work has shown that such an event seems likely to occur in the next century, with a 12 per cent chance of it happening in the next decade, but nobody seems to be all that worried, Loeb says. Asteroid impacts get all the attention when it comes to life-threatening space events, but Loeb and Lingam found that superflares would be just as deadly and are just as likely.

“I’m not lying awake in bed at night worrying about solar superflares, but that doesn’t mean that someone shouldn’t be worrying about it,” says Greg Laughlin at Yale University.

Last month, Loeb and Lingam came up with one potential way to protect Earth from superflares both large and small: an enormous loop of conductive wire between us and the sun that could act as a magnetic shield and deflect flares’ particles away.

Unfortunately, launching such a shield into space would cost upwards of $100 billion. “I think that seriously diverting resources to build a wire loop in space would not be the best way to spend money,” says Laughlin. “But thinking more about how solar superflares work and getting a sense of how our sun fits in with its peers would be a very valuable effort.”

Journal reference: The Astrophysical Journal, DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa8e96

Read more: Most powerful flare ever seen erupts on nearby star

PJMFett on October 16th, 2017 at 14:27 UTC »

Would airplanes fall out of the sky?

BattleHall on October 16th, 2017 at 14:02 UTC »

This has always been one of my fears, but when the topic came up recently in another thread, someone responded who said they work in power grid infrastructure and that (maybe, hopefully) the danger is a bit overstated. IIRC, they said that the biggest change has been the advent of digital grid controls over the last 10-15 years in order to detect things like outages, spikes, voltage and cycle matching between generation sources, etc. They said that although solar flares have the ability to generate immense induced currents in long conductors, they actually have a relatively slow rise, and that modern safety controls should trip before they cause damage to the hard-to-replace components that are always the crux of these stories. I could be misremembering it, though; does anyone with any expertise in this area want to weigh in?

Rhianonin on October 16th, 2017 at 13:38 UTC »

If this were to happen, how long would the grids be out for? Weeks? Months?