By the mid-1800s, the River Thames had been used as a dumping ground for human excrement for centuries. At last, fear of its ‘evil odour’ led to one of the greatest advancements in urban planning: Joseph Bazalgette’s sewage system

In the steaming hot summer of 1858, the hideous stench of human excrement rising from the River Thames and seeping through the hallowed halls of the Houses of Parliament finally got too much for Britain’s politicians – those who had not already fled in fear of their lives to the countryside.

Clutching hankies to their noses and ready to abandon their newly built House for fresher air upstream, the lawmakers agreed urgent action was needed to purify London of the “evil odour” that was commonly believed to be the cause of disease and death.

The outcome of the “Great Stink”, as that summer’s crisis was coined, was one of history’s most life-enhancing advancements in urban planning. It was a monumental construction project that, despite being driven by dodgy science and political self-interest, dramatically improved the public’s health and laid the foundation for modern London.

You’ll see no sign of it on most maps of the capital or from a tour of the streets, but hidden beneath the city’s surface stretches a wonder of the industrial world: the vast Victorian sewerage system that still flows (and overflows) today.

London is, of course, an ancient metropolis, but according to the city’s prolific biographer (and Londoner) Peter Ackroyd, the 19th century “was the true century of change”. And by the mid-1800s, reform of the capital’s sanitation, like much else in the nation’s political and social life, was long overdue.

For centuries, the “royal river” of pomp and pageantry, the city’s main thoroughfare, had doubled as a dumping ground for human, animal and industrial waste. As London’s population grew – and it more than doubled between 1800 and 1850, making it by far the largest in the world – the build-up of waste itself became a spectacle no one wanted to see, or smell.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest 1858: A satirical cartoon from Punch magazine shows a skeleton rowing along the Thames. Illustration: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

With a lack of planned housing and infrastructure to support the crowded citizenry, increasingly filthy streams, ditches and antiquated drainage pipes all bubbled into the Thames, where the detritus simply bobbed up and down with the tide. The apparent progress of flushing toilets (marketed to the masses at the Great Exhibition in 1851) only made things worse, overwhelming old cesspools and forcing ever more effluent into the river, which belched it back into the city at each high water.

The “silver Thames” eulogised by earlier poets had become, in the words of the Royal Institution scientist Michael Faraday in 1855, “an opaque pale brown fluid”. Dropping pieces of white paper into the river, Faraday found that they disappeared from view before sinking an inch below the surface. All too clear was the main contaminant: “Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface, even in water of this kind,” he wrote.

Faraday’s report of the dire straits of “Father Thames” was echoed in numerous editorial columns and cartoons that scorned the once-majestic river’s demise into the most polluted metropolitan waterway in the world. The British empire was literally rotting at the core.

“Through the heart of the town a deadly sewer ebbed and flowed, in the place of a fine fresh river,” Charles Dickens wrote in Little Dorrit (1855-57). The fetid fumes alone, it was thought, could strike a man dead. What made the water lethal, however, was that a great many Londoners were drinking it piped directly from the Thames. Even water pumped from outside the city risked contamination with sewage when it reached the squalid streets, and the wells still in use lay dangerously close to leaking cesspools.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Dr John Snow’s cholera water pump replica in Broad Street, London. Photograph: Alicia Canter/Observer

In 1834, the humorist cleric Sydney Smith vividly described the unpalatable truth: “He who drinks a tumbler of London water has literally in his stomach more animated beings than there are men, women and children on the face of the globe.”

The result was successive waves of waterborne diseases such as dysentery, typhoid and, most feared of all by mid-century, cholera. For this “Victorian plague”, as the historian Amanda J Thomas characterises it, there was no known cure – whatever quacks claimed – and the wealthy were not immune. The first major cholera epidemic in Britain, in 1831-32, killed more than 6,000 Londoners. The second, in 1848-49, took more than 14,000. Another outbreak in 1853-54 claimed a further 10,000 lives.

With the bodies piling up, the people and the press pushed for change. The working class basket-maker and poet Thomas Miller wrote in the Illustrated London News: “Let us then agitate for pure air and pure water, and break through the monopolies of water and sewer companies, as we would break down the door of a house to rescue some fellow-creature from the flames that raged within. It rests with ourselves to get rid of these evils.”

Investigating cholera’s spread in Soho in 1854, the physician Dr John Snow deduced that the cause was contaminated water. His evidence included the 70 workers in the local brewery who only drank beer and all survived. Yet public health officials were slow to be convinced. The “miasma theory” that diseases were caused by noxious vapour in the air held stubborn sway, leading the well-meaning social reformer Edwin Chadwick – insisting that “all smell is disease” – to hasten the abandonment of stinking cesspools in favour of flushing the sewers into the Thames. The effect was more ill than good.

His arguments largely dismissed, Dr Snow died in 1858 at the height of the Great Stink, a “miasmatic” event that helped prove his point by failing to unleash a new outbreak of disease – if miasma were deadly, the Great Stink surely would have been.

By overpowering the politicians in the Houses of Parliament, though, the stench still proved a catalyst for change. The miasmatists were at least right about one thing: the reeking river correlated with the city’s health, and needed to be cleaned.

As MPs shrouded themselves behind curtains soaked with chloride of lime to counter the fumes, they couldn’t say they hadn’t been warned. Just a few years earlier, Faraday had urged officials that they could not ignore the state of the Thames “with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if, ere many years are over, a hot season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness”. In the heatwave of 1858, the stagnating open sewer outside Westminster’s windows fermented and boiled under the scorching sun.

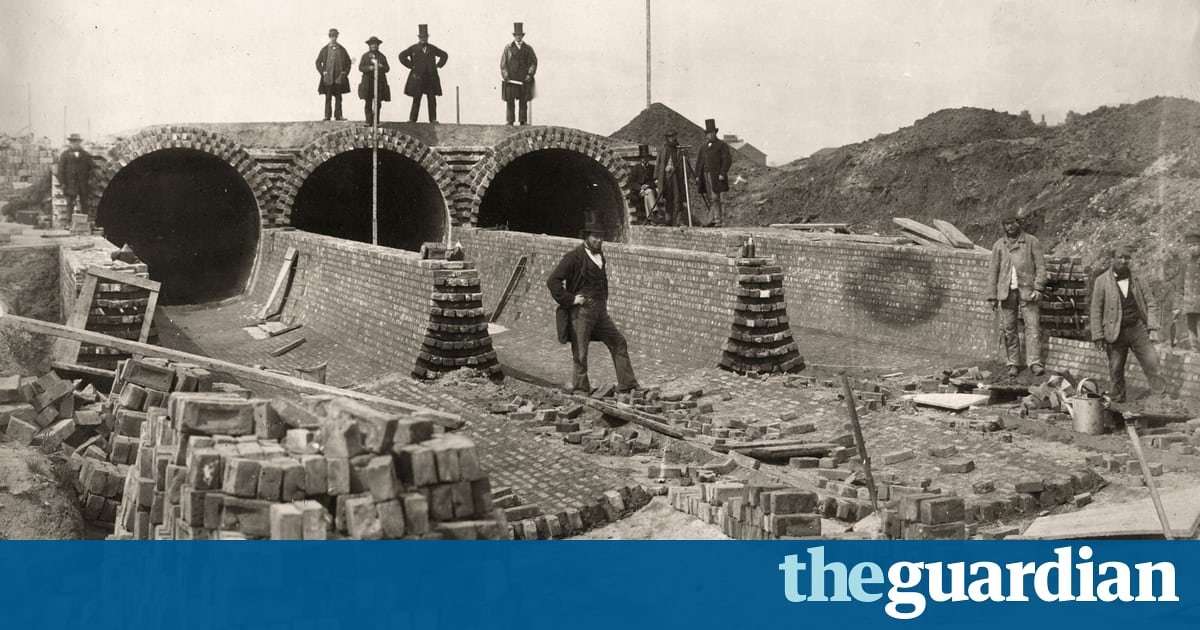

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Workmen building the northern outfall sewer and overflow into the River Lea in 1862. Photograph: Otto Herschan/Getty

Benjamin Disraeli, the Tory leader in the Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer, lamented how “that noble river” had become “a Stygian pool reeking with ineffable and unbearable horror”, and introduced legislation “for the purification of the Thames and the main drainage of the metropolis”.

Up to this point, London had lacked a unified authority with the money required to address such an extensive problem of sanitation on an effective scale. Now the recently formed Metropolitan Board of Works was empowered to raise £3m and instructed to start work without further delay. The board’s chief engineer, Joseph Bazalgette, who had already spent several exasperating years drawing up plans for an ambitious new sanitation system, only for each one to be swiftly shelved, at last got the go-ahead to begin construction.

Stephen Halliday, author of The Great Stink of London, explains: “Bazalgette’s plan, which was modified in some details as construction progressed, proposed a network of main sewers, running parallel to the river, which would intercept both surface water and waste, conducting them to the outfalls at Barking on the northern side of the Thames and Crossness, near Plumstead, on the southern side.” These combined sewers thus diverted rainwater and effluent downstream, well beyond the built-up city to the east, from where it would flow more easily out to sea.

The network included 82 miles of new sewers, great subterranean boulevards that in places were larger than the underground train tunnels then under construction. With a minimum fall of two feet per mile, the main drainage sewers employed gravity to conduct their contents downstream, while smaller sewers were egg-shaped (narrower at the bottom than the top) to encourage the flow.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Victorian overflow sewers are still in use today but with a growing population in London, the Thames is under severe strain. Photograph: Mark Lovatt/Getty Images/Flickr Open

Pumping stations were built at Chelsea, Deptford, Abbey Mills and Crossness to raise up sewage from low-lying areas and discharge it onwards to the outfalls. The latter two especially were architecturally magnificent, evocative of cathedrals in their design, dimensions and ornament. Symbolic of the grandeur of the entire project, they proudly announced their role in forging a more wholesome and, perhaps, holy London.

The scheme also involved the huge challenge of embanking the Thames, creating the Victoria, Albert and Chelsea embankments. Informed by Bazalgette’s experience of land drainage and reclamation while working as a railway engineer, London’s embankments were designed not only to carry tunnels (including the underground railway), but also to help cleanse the river by narrowing and strengthening its flow through the city’s centre.

Halliday notes that while the embankments were Bazalgette’s “most conspicuous works” for which he received the greatest credit – it is on Victoria Embankment that a monument to the engineer, who was knighted in 1875, may be found – he himself regarded the main drainage as his greatest achievement: “It was certainly a very troublesome job,” Bazalgette reflected. “It was tremendously hard work.”

The hard work of thousands of labourers overseen by Bazalgette inspired the artist Ford Madox Brown as he painted Work, a large canvas completed in 1865, the same year that the main drainage works were opened at Crossness by the Prince of Wales (though the construction in fact continued for another decade). Brown’s image is bursting with activity and society – rich and poor, young and old, rural and urban – but all this revolves around and, we may infer, depends on the industrious workmen at the centre, building an enlightened tunnel below ground.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Ford Madox Brown’s Work, 1852-1863, was inspired by the construction of the sewer system. Photograph: Dea Picture Library/De Agostini/Getty Images

Framed by forearms and tools, a hod carrier descends into the depths with more bricks: a building material that Bazalgette’s project employed in such vast quantities – 318m – that prices escalated along with the wages of bricklayers, who down-tooled to secure a rise from 5 to 6 shillings a day.

According to the Observer newspaper, “every penny spent is sunk in a good cause” in the creation of this “most extensive and wonderful work of modern times”. And the work almost immediately proved its worth: in 1866, most of London was spared from a cholera outbreak which hit part of the East End, the only section not yet connected to the new system.

“What was extraordinary about Bazalgette’s scheme was both its simplicity and level of foresight,” writes Paul Dobraszczyk in London’s Sewers. A classic piece of Victorian over-engineering, the infrastructure was planned to accommodate a population growth of 50%, from 3 million to 4.5 million. Within 30 years of its completion, the city’s population had in fact doubled again, reaching 6 million. It is testament to the quality of design and construction that, with improvements and additions, the 19th-century system remains the backbone of London’s sewers in the 21st century.

But the backbone is now severely strained. With a still-expanding population, dramatic downpours associated with climate change and the loss of green spaces to soak up the excess, the Thames is once again at risk.

Bazalgette provided for extreme weather with overflows into the river, to prevent the flooding of homes and streets. And those overflows are now being used more than ever – around 50 times a year – dumping raw sewage under the noses of present-day MPs in Westminster.

The story of cities #15: the rise and ruin of Rio de Janeiro's first favela Read more

Martin Baggs, the outgoing chief executive of Thames Water, has been upfront about the challenges. “They say that history repeats itself: 150 years ago the River Thames was polluted; that’s where we are again today. Was it acceptable 150 years ago? No, it wasn’t. Is it acceptable today? No, it’s not. We’ve got to do something about it.”

Construction of the company’s solution, the Thames Tideway Tunnel – or “super sewer” – is due to begin this year, for completion in 2023. One of the largest civil engineering projects the country has ever seen, and not without controversy, the tunnel is a “visionary work of modern times”, in Ackroyd’s view, “in the spirit of Bazalgette”.

Hopefully Ackroyd is right. That great engineer shared some wise words based on his own experiences of re-planning London: “Private individuals are apt to look after their own interests first, and to forget the general effect upon the public. It is necessary that there should be somebody to watch the public interests.”

Does your city have a little-known story that made a major impact on its development? Please share it in the comments below or on Twitter using #storyofcities

danksweater on September 27th, 2017 at 13:34 UTC »

I used to work in a small family brewery. It was literally a job requirement to test every holding tank in the cool room every morning, to test flavour/carbonation and make sure no infection had occured. I was moderately drunk by 10am and getting paid to do it.

SeriesOfAdjectives on September 27th, 2017 at 12:27 UTC »

He traced it to a particular water pump through an intricate map of who was getting sick. They made the pump off-limits for people to use and the case rate plummeted.

satanicpuppy on September 27th, 2017 at 12:01 UTC »

For a good book about this, check out The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson.