With the potential to provide almost limitless energy, free of any radioactive by-product or greenhouse gases, nuclear fusion is the goal many are aiming to achieve.

Creating a system to harness the power of nuclear fusion is proving difficult, however. Now, researchers think they have taken a step closer to that goal.

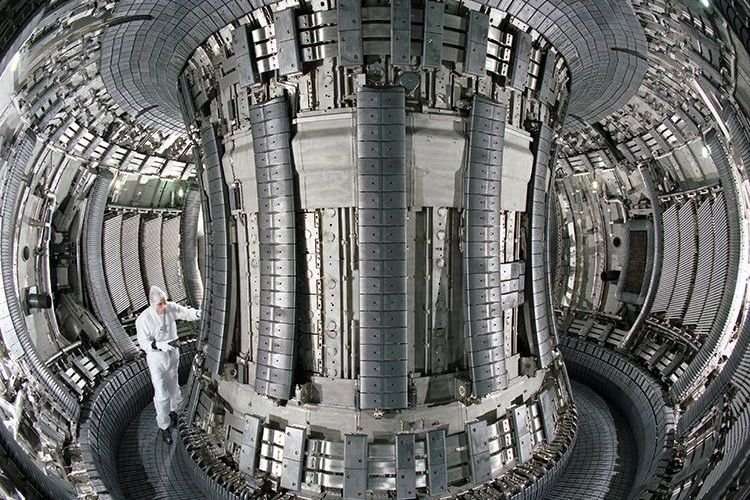

It takes immense pressure and temperatures of about 150 million degrees to get atoms to combine in a fusion reactor. Runaway electrons can wreak havoc in the fusion reactors currently under development and could destroy a reactor without warning.

READ NEXT We're one step closer to nuclear fusion energy We're one step closer to nuclear fusion energy

The new technique works by decelerating these runaway electrons. This is done by injecting heavy ions, such as argon or neon in the form of gas or pellets, into the reactor. Electrons collide with these atoms, slowing them down.

"When we can effectively decelerate runaway electrons, we are one step closer to a functional fusion reactor," said Chalmers University of Technology's Linnea Hesslow, co-author of the paper.

READ NEXT Nuclear island: The secret post-WWII mega lab investigated Nuclear island: The secret post-WWII mega lab investigated

“Considering there are so few options for solving the world's growing energy needs in a sustainable way, fusion energy is incredibly exciting since it takes its fuel from ordinary seawater.”

Nuclear fusion is the energy source of the stars. Deep in our Sun's core, hydrogen atoms slam into one another at high speed, getting "mashed" together to form helium atoms, all the while releasing copious amounts of energy.

Creating viable fusion energy on Earth has been an ideal since the dawn of the Atomic Age.

With true fusion power, the amount of water you use in a single shower could provide all your energy needs for a year. But for six decades, fusion has remained a far-off dream.

"The interest in this work is enormous," said Professor Tünde Fülöp, who led the students' work on the paper. “The knowledge is needed for future, large-scale experiments and provides hope when it comes to solving difficult problems. We expect the work to make a big impact going forward.”

At the moment, all eyes are on the research collaboration developing the ITER reactor in southern France.

"Many believe it will work, but it's easier to travel to Mars than it is to achieve fusion," continued Hesslow. “You could say that we are trying to harvest stars here on Earth, and that can take time. It takes incredibly high temperatures, hotter than the centre of the Sun, for us to successfully achieve fusion here on Earth. That's why I hope research is given the resources needed to solve the energy issue in time.”

The paper is published today in the journal Physical Review Letters.

atom_anti on June 21st, 2017 at 13:59 UTC »

I am one of the co-authors of this paper. Ask me anything, I try to answer if I can. By the way, wired blew the story out of proportion a bit - but I will shamelessly use this opportunity to answer questions you may have about fusion. You can read the PRL itself to know what we wrote. Freely avaliable on https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.08638

mvea on June 21st, 2017 at 12:35 UTC »

Journal reference:

Effect of Partially Screened Nuclei on Fast-Electron Dynamics

L. Hesslow, O. Embréus, A. Stahl, T. C. DuBois, G. Papp, S. L. Newton, and T. Fülöp

Physical Review Letters 118, 255001

Published 20 June 2017

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.255001

Link: https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.255001

Abstract:

UPDATE:

Co-author of paper is commenting and doing an informal AMA in this thread here:

https://www.reddit.com/r/Futurology/comments/6il2wl/comment/dj77r7n

rudysus23 on June 21st, 2017 at 12:29 UTC »

Alright, r/Futurology, tell me why this isn't going to work.