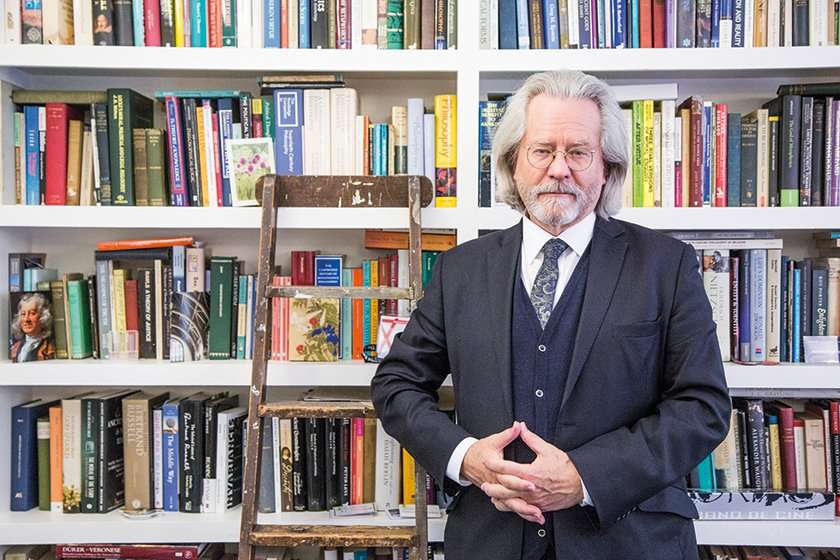

Professor of philosophy and master of New College of the Humanities, AC Grayling, believes that children should be taught philosophy from the age of six.

The literal meaning of philosophy is ‘love of wisdom’ – an inspiring but unhelpful fact. A far better definition is ‘careful enquiry’, with no limit on what the enquiry is about. In ancient times, it included everything we now think of as science, history, ethics, politics, sociology and more.

Today, in the university study of philosophy, a more specialist range of subjects arise: the nature of knowledge and how we get it, reason and reasoning, the concepts of morality and society and mind and consciousness.

What do we learn from philosophy?

One of the most important aspects of philosophy is that it asks us to challenge our assumptions and the frameworks of thought that we live by. It requires us to ask ourselves sharp questions about why we think the way we do about ourselves, others and the world around us. Many hidden assumptions lie buried in our systems of thought and, if we do not examine them, we are at risk of being misled or misguided by those systems if they are wrong.

Above all, philosophy is a method. It requires the analysis of ideas and concepts, examination of theories and creative and imaginative efforts to construct ways of thinking that throw fresh light on the problems and puzzles that our fascinating, and sometimes difficult, world throws at us.

It is the last two points which explain why philosophy, if it were a core subject throughout the school years, would be a powerful addition to all other subjects studied, and a booster to the mental and intellectual capacities of students. Primary school children are instinctively good at philosophical problems the moment they are presented with them.

How young can you learn philosophy?

I have seen six-year-olds energetically and brilliantly address the question, ‘what happens to the hole in the doughnut when the doughnut is eaten’ and 12-year-olds become animated when discussing whether or not the classroom table exists when no-one is there. I have seen sixth-formers become deeply engaged with ethical and political questions of genuine importance regarding how we live our lives and treat others.

The combination of vividly interesting questions and the demand to think things through with care and rigour is what makes philosophy so instantly attractive to almost all students when they encounter it. They quickly come to see that even when there are no obvious answers to some of the dilemmas that thinking about our world presents to us, the effort involved in exploring them is a highly instructive and creative one. As the French poet Paul Valery said, ‘A difficulty is a light; but an insurmountable difficulty is the sun.’

If I were given the chance to devise a philosophy programme for schools, I would begin with-six year-olds and the delightful play of ideas and questions they so enjoy. By drawing attention to what we take for granted, they begin to learn to think for real purpose. The question about the doughnut, for example, makes them consider – even if they do not use these words themselves – what we mean by space, time, things, relations, existence, change and more. They do not grasp these concepts fully or understand all their implications yet, but they would have begun the fascinating process of thinking ‘outside of the box’ and constructively realising that not everything we take for granted should be.

From these beginnings, in asking questions and thinking through and around ideas, I would have the students move progressively into more detailed and in-depth stages of debate. This would eventually lead to reading and discussing some of the great philosophers of the past (most of the classics of philosophy are more accessible than people suppose) and relating them to the fields of study, such as science, which arose from philosophical enquiry and still prompt philosophical questions.

It has been amply proved by the excellent International Baccalaureate system that a strand of philosophical study in a curriculum (the IB’s ‘Theory of Knowledge’, for example), when taught well, gives a huge boost to students’ capabilities in all other subjects. For this reason alone, philosophy should be a central school subject, from start to finish.

TheTurnipKnight on June 8th, 2017 at 14:13 UTC »

Philosophy yes, but not the history of philosophy. The last thing you want is to bore kids to death so they never touch philosophy again in their life. So many teachers make this mistake.

Edit: Philosophy and History of Philosophy are two different areas of knowledge. It would be more beneficial to learn about the first area than the second area for kids, because history is always gonna be more boring and less concise. Teaching just Philosophy you don't necessarily need to teach just chronologically, you can jump all around history and pick ideas and people that are sort of related and focus on the most interesting parts and how you can understand them. That is what would be fascinating for someone who is just starting to learn about philosophy (it certainly was for me).

danielt1263 on June 8th, 2017 at 11:41 UTC »

Logic is a core part of philosophy and should be taught at least in high school, possibly sooner. We start kids in algebra as early as middle school. Predicate logic is very much like algebra and more relevant for life so it should be taught at the same age. Inductive reasoning is even more important in life. These philosophical foundations should absolutely be taught much earlier than they currently are.

ofrm1 on June 8th, 2017 at 10:16 UTC »

Ethics ought to be a course that is required to graduate high school and get a degree in college. The latter used to be the case a long time ago.

A principles of reasoning course would go a long way toward high school students being able to determine what arguments are good and bad.