For some, brave works and contributions are done anonymously because the person would rather their efforts speak for themselves.

For Henrietta Lacks, her gift to the world was given without her consent, without her family’s permission, without attribution or compensation or acknowledgment for nearly half a century.

Without her, there would be no polio vaccine; there’d be fewer treatments for cancer; there’d be fewer medical treatments at al. And all it took was a group of powerful cancer cells too strong to die.

Henrietta was just 31 when cervical cancer took her life, leaving her five children without a mother. She was the daughter of tobacco farmers and grew up in Virginia, not too far removed from slaves in her own family tree. She married David “Day” Lacks, a cousin, after having two children with him (Lawrence, when she was 14, and Elsie when she was 18) and the family moved to Baltimore in 1941 so he could pursue work at the Bethlehem Steel plant there.

It was after the birth of her last child, Joseph, that Henrietta first fell ill. She reportedly went to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, one of the few in the region that would treat black patients, and told them she felt a “knot” in her womb. When she’d felt a similar discomfort earlier, her cousins told her not to worry about it, that she was likely pregnant, and in previous instances they were correct.

This time, however, there were complications with Joseph’s delivery and Henrietta suffered a severe hemorrhage. One doctor tested her for syphilis, which came back negative, so a second doctor, Howard Jones, took a biopsy of some cells from her cervix, leading to her diagnosis.

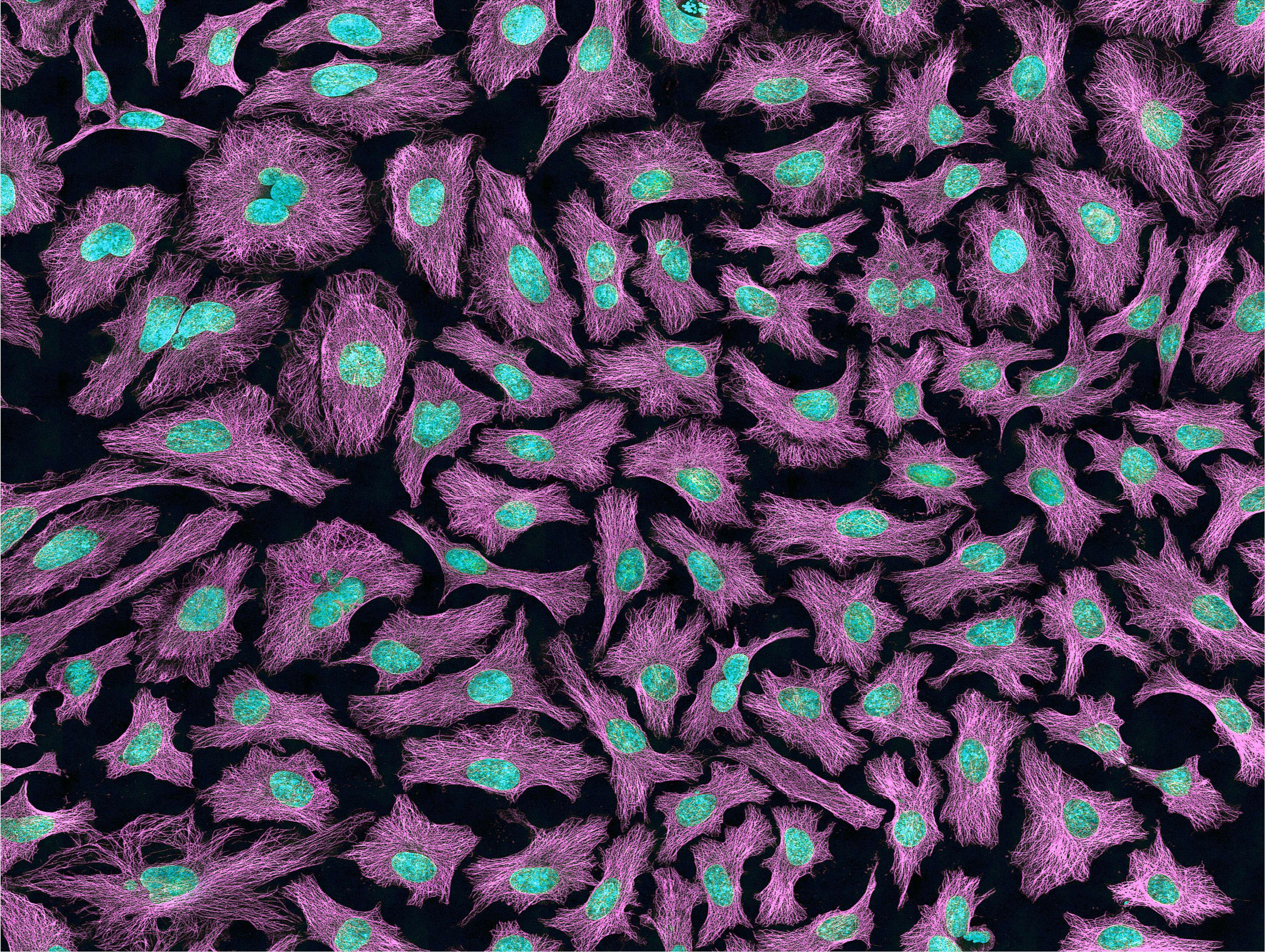

It was during her treatment for cancer that doctors removed some of the tumor and kept the cells in a lab. For years, doctors and researchers had been trying to get cells to replicate and stay alive for longer than a few hours outside their host but it had never been successful. Henrietta’s cells were different – they not only stayed alive, they kept replicating.

Henrietta died from her cancer in October 1951, having been admitted to the hospital for severe abdominal pain in August and never released after the cancer spread through her body.

What Lacks did for modern medicine

Meanwhile, a team of researchers, led by George Otto Grey, kept working with and cultivating the cells. Henrietta’s cells were the first immortal human cells grown in culture inside a lab. Coded HeLa so as not to disclose their “donor,” the cells were shared with other research facilities.

The cells alone were tremendous for not dying shortly after being harvested, but they became the keystone of modern medicine in many ways. Without research based on HeLa cells, there would be no polio vaccine, no drug treatment for people with HIV and AIDS. There would be a shortage of cancer treatments.

The ability of HeLa cells to survive made research possible. Doctors could, for the first time, apply new and experimental treatments on cells and see what would happen. They could inject the cells with a new virus and run experiments. They could inject the cells with other carcinogens and monitor the response.

The cells have been hit with nearly every treatment and illness imaginable since they were harvested in 1951. The cells have been used so frequently, one researcher has said HeLa cells could wrap around the planet at least three times if placed end to end. Some 10,000 patents have been issued for treatments that began with HeLa cells.

So much good has come from the cells that it would not be unrealistic for HeLa and Henrietta Lacks to be a storied legend in the medical world, whose name is taught alongside Christiaan Barnard, the surgeon behind the first successful adult heart transplant, and Jonas Salk, developer of the first successful polio vaccine. But until the 1970s, not even Henrietta’s own family knew her cells had been removed and used for research.

The Lacks family was kept in the dark

After living and replicating outside Henrietta’s body for more than 15 years, researchers learned that the cells had become contaminated. Thinking maybe whatever made the HeLa cells special could be found in members of her immediate family, doctors at Johns Hopkins contacted members of Henrietta’s family in 1973 and asked for blood samples.

They agreed but weren’t really told why the samples were being collected. They started asking questions, especially after a family friend asked during a dinner party if they were related to the “mother of the HeLa cell.” Puzzled, they demanded answers, only to learn, years later, the truth of their mother’s contribution to science and research.

No permission was ever asked of Henrietta to collect her cells because that was not common practice at the time. No money ever exchanged hands because, again, Henrietta would’ve had to give permission and been told what her cells would have been used for, and even then there would’ve been no guarantee anything would come from the samples that were collected.

As of 2010, a tube of HeLa cells sells for about $260 USD.

The story behind HeLa cells is finally told

Rebecca Skloot first heard Henrietta’s name in a biology class in 1988 when her instructor was talking about cell mitosis, abnormalities and cancer, bringing up HeLa cells and saying nothing was known about the woman responsible for them. Skloot was curious and couldn’t get the story out of her mind.

After getting her degree in biological sciences, Skloot spent the next decade or more researching Henrietta, her family and her history, trying to solve the mystery. She became close with some members of the Lacks family, including her youngest daughter, Deborah, but had tension with Henrietta’s oldest son Lawrence, who wanted many things discussed among his family kept private.

But ultimately some good has come from Skloot’s work with the family, in addition to her book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, a New York Times bestseller and now an HBO movie starring Oprah Winfrey as Deborah Lacks. (Deborah, portrayed in the book and movie as the guardian of her mother’s legacy, passed away in 2009, just before the book was published.)

In 2013, the US National Institutes of Health came to an agreement with the Lacks family, giving them control over how her cells are used and where they are distributed. They will not be compensated under this agreement but their family’s contributions to medical science will be acknowledged in any research paper that involves treatment using HeLa cells.

Two members of the family now sit on a six-member committee that regulates access to the cells as a way to ensure their privacy and genetic information remains protected.

Oryzanol on May 19th, 2017 at 13:40 UTC »

Considering the mass of all the cells that came from her cancer sample, would that make Henrietta Lacks one of the largest organisms in the world?

blackesthearted on May 19th, 2017 at 12:16 UTC »

The book "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" by Rebecca Skloot is a great read for anyone interested in her story (and her family's, especially her daughter Deborah); the HBO film and RadioLab episode are based on it.

DocAfri on May 19th, 2017 at 10:33 UTC »

Lol ....ummm involuntarily might be a key word missing here