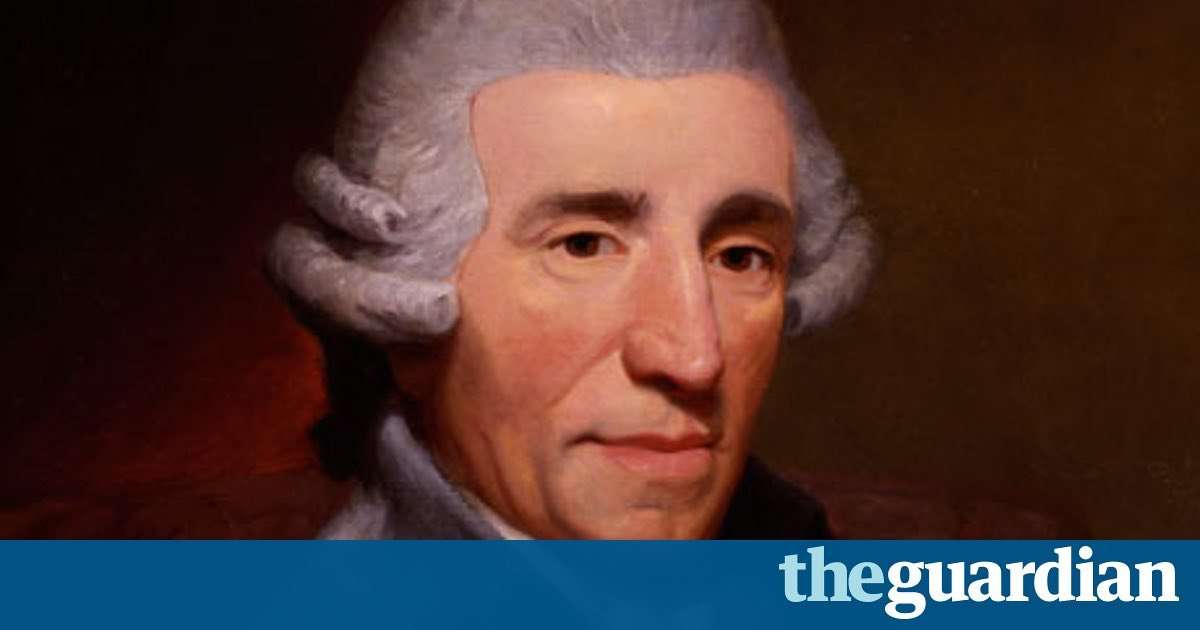

The evening of 2 February, 1795, at the King's Theatre, London. The audience awaits with keen anticipation the performance of a new symphony by the city's most famous musical visitor, the 62-year-old Joseph Haydn. It is a time of war, revolutionary fervour, and establishment-threatening radicalism. As the concert advertised that Haydn would direct the new piece himself "from the Pianofort"', the audience "pressed forward towards the orchestra", as AC Dies reported, trying to see the master at close range. That neatly emptied the middle of parterre of spectators, which meant that when a chandelier crashed from the ceiling into the floor, it conveniently hit only empty seats rather than bewigged heads. "Miracle! miracle!" the audience shouted. As Dies wrrote: "Haydn himself was much moved, and thanked merciful Providence who had allowed it to happen that he could, to a certain extent, be the reason, or the machine, by which at least thirty persons' lives were saved. Only a few of the audience received minor bruises."

No less miraculous than those few bruises was the symphony Haydn was about to perform. Confusingly, this isn't the symphony with the epithet "The Miracle", no 96; the chandelier actually fell at the first performance of Haydn's 102nd symphony, in B flat major. All 12 of the symphonies Haydn wrote for his two trips to London – in 1791 and 1795 – prove how he developed the symphony from courtly entertainment to public spectacle. Simultaneously, these pieces mark a watershed in what the symphony means in social and even political terms, and they mark an expansion of the symphony's musical ambitions. I could have chosen any of the pieces known as numbers 93-104; 102 just happens to be a favourite.

By the time Haydn was preparing for his second visit to London, he knew what to expect from his audiences. He knew how much this middle-class audience of concert-goers – among the first properly public, as opposed to aristocratic, audiences for symphonic music in history – understood and appreciated his invention, his games of expectation and surprise, his effortless manipulation of genre, affect, and expressivity. And he knew he could push them and himself even further when he came back, when his celebrity and status were even greater than before. That means these symphonies are, in effect, palimpsests of listening, pieces composed with their effectiveness for a musically literate audience in mind. Haydn needed to keep surprising his London audiences, and to do that, he became still more skilful and economical – as well as bold and chandelier-breakingly shocking – in his deployment of his symphonic resources.

In the 102nd Symphony, that plays out in the lyrical slow introduction Haydn composes at the very start of the piece, whose alternation of serenity and aching chromatic harmony dissolves in a delicious filigree of flute arpeggio before the main vivace section of the movement. Haydn turns this movement into a miniature musical roller-coaster of the flouting of classical conventions. Just when you think you've safely arrived at the end of the first part of the movement in a stable key, a steamroller-like (to mix various mechanical metaphors) semibreve stops the music in its tracks, before Haydn wrenches the music back to where it's supposed to be. In the central section of the vivace, Haydn atomises his themes into discombobulated fragments, puts them together in some chaotic high-octane counterpoint, and then engineers a return to the main theme. But all is not as it seems: we're in the wrong key, so Haydn plunges us back into a tempestuous modulatory foment before the movement's real moment of return, 40 bars later.

Haydn's symphonic rhetoric is so brilliantly calibrated that you feel the drama of the music instinctively without needing a background of keys, structures, and conventions – but his first audiences in the 1790s would certainly have understood what was going on. The slow movement, a transcription of the adagio from his F sharp minor Piano Trio, features some of Haydn's most dream-like music, yet the idyll of the solo cello obbligato underneath the ornate, ornamented main melody is unsettlingly accentuated by the soft pulses of the timpani. In the Menuet that comes next, it's the languid trio that stands out for me, especially with the chromatic inflections of its second section. And the finale, after its impish beginnings, finds some obsessive moments of momentum and joyously churning dissonance that Beethoven must have known: the finales of his Second and even Seventh symphonies are foreshadowed in passages like this. But Haydn's 102nd, just like all of his London symphonies, consecrates a moment in symphonic history when this composer and his listeners were in excellent, mutually appreciative accord, a bond that's renewed every time this symphony is played or listened to today.

Nikolaus Harnoncourt/Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra: a balance of Harnoncourt's puckish fantasy and the Concertgebouw's innate warmth.

Thomas Beecham/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra: from another era, maybe, but Beecham's insights into Haydn are still unique.

Simon Rattle/City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra: Rattle conducts a radiant, generous, and clearly-characterised performance.

Eugen Jochum/London Philharmonic Orchestra: Jochum's is a no-nonsense vision of the symphony, which paradoxically enhances its weirdnesses!...

Sigiswald Kuijken/La Petite Bande: Kuijken's Haydn puts his iconoclasm front and centre in his period instrument performance.

Jambooflamingo on May 16th, 2017 at 23:33 UTC »

I love these random historical music stories, like when Stravinsky's Rite of Spring first premiered in Paris in 1913, it was such a new and strange music style (very dissonant and not pleasant sounding) that people rioted.

DumasThePharaoh on May 16th, 2017 at 21:39 UTC »

The theatre was delighted, no one died

Alice_B_Tokeless on May 16th, 2017 at 19:49 UTC »

Good one.

I thought I'd heard most of these musical premiere stories, but this one is new to me.