Until now, art historians dismissed some doodles in da Vinci’s notebooks as “irrelevant.”

But a new study from Ian Hutchings, a professor at the University of Cambridge, showed that one page of these scribbles from 1493 actually contained something groundbreaking: The first written records demonstrating the laws of friction.

Although it has been common knowledge that da Vinci conducted the first systematic study of friction (which underpins the modern science of tribology, or the study of friction, lubrication, and wear), we didn’t know how and when he came up with these ideas.

Hutchings was able to put together a detailed chronology, pinpointing da Vinci’s "Aha!" moment to a single page of scribbles penned in red chalk in 1493.

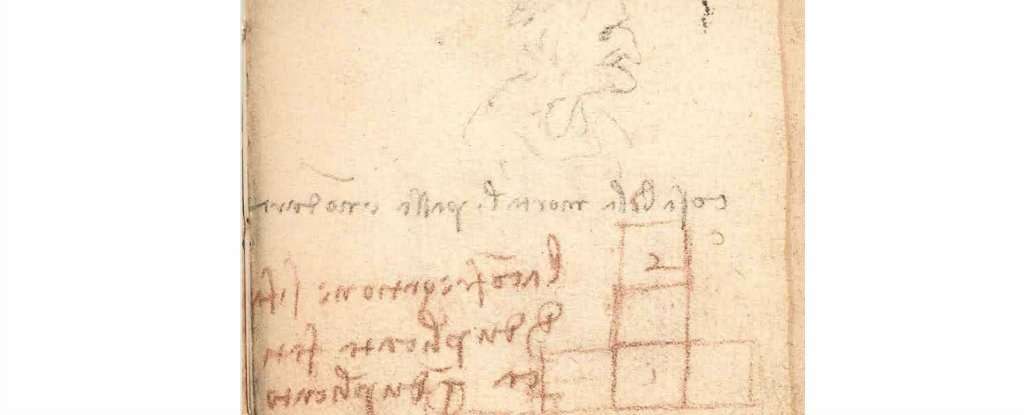

According to Gizmodo, the page drew attraction towards the beginning of the 20th century because of a faint etching of a woman near the top, followed by the statement "cosa bella mortal passa e non dura", which translates to "mortal beauty passes and does not last".

But a 1920s museum director dismissed the page as "irrelevant notes and diagrams in red chalk".

Almost a century later, Hutchings thought this page was worth a second look. He discovered that the rough geometrical figures drawn underneath the red notes show rows of blocks being pulled by a weight hanging over a pulley – in exactly the same kind of experiment students might do today to demonstrate the laws of friction.

"The sketches and text show Leonardo understood the fundamentals of friction in 1493," said Hutchings in a University of Cambridge press release.

"He knew that the force of friction acting between two sliding surfaces is proportional to the load pressing the surfaces together and that friction is independent of the apparent area of contact between the two surfaces. These are the 'laws of friction' that we nowadays usually credit to a French scientist, Guillaume Amontons, working two hundred years later."

Hutchings was also able to show how da Vinci went on to use his understanding of friction to sketch designs for complex machines over the next two decades. Da Vinci recognised the usefulness and effectiveness of friction and worked the concept into the behaviour of wheels, axles, and pulleys – integral components of his complicated machines.

"Leonardo’s 20-year study of friction, which incorporated his empirical understanding into models for several mechanical systems, confirms his position as a remarkable and inspirational pioneer of tribology," Hutchings said.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

dodgy-stats on May 13rd, 2017 at 17:08 UTC »

Cambridge university has a more detailed description of the findings. They have also released a paper which goes into a lot more detail.

The note Da Vinci has scribbled reads

which translates to 'the friction is of double the effort for double the weight'.

The drawing shows 3 blocks stacked on top of each other superimposed by 3 blocks stacked next to each other. Both sets of blocks appear to be attached to a horizontal line (a rope) which runs over a pulley and is connected to a circular weight hanging down. This suggests that Da Vinci had also worked out that the force of friction was independent of the contact area (the three bricks stacked vertically have only the contact area of a single block).

NewNewTwo on May 13rd, 2017 at 16:43 UTC »

How did this guy be so good at everything?

pike360 on May 13rd, 2017 at 15:25 UTC »

This is why I keep all my yellow pads. Someday, I hope to find something of value within all the nonsense.