Sign up for our amNY Sports email newsletter to get insights and game coverage for your favorite teams

The heirs of a Jewish family that fled Nazi persecution are demanding the repatriation of a Pablo Picasso painting they once owned now in possession of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, which the family says is worth up to $200 million today.

The descendants of Karl Adler and Rosi Jacobi, backed by several Jewish charities, filed a lawsuit against the Guggenheim in Manhattan Supreme Court on Jan. 20, demanding the return of Picasso’s “Woman Ironing,” a 1904 work from the artist’s Blue Period, and restitution for the painting’s present estimated value of $100-200 million.

In the lawsuit, the couple’s great-grandson, Thomas Bennigson, says the pair were forced to sell the masterpiece at a substantial loss while they frantically attempted to escape persecution by the Nazis in their native Germany in 1938, a shared experience of many Jewish families whose art was plundered by the Germans.

“Adler was forced to sell the Painting for well below its actual value,” reads the suit. “Adler would not have disposed of the Painting at the time and price that he did, but for the Nazi persecution to which he and his family had been, and would continue to be, subjected.”

In the beginning of the 20th century, Adler was chairman of the board at Adler & Oppenheimer A.G., one of Europe’s most prominent leather manufacturers, and the family lived a prosperous lifestyle; in 1916, Adler purchased “Woman Ironing” from Heinrich Thannhauser, a Munich gallery owner.

That all changed when the Nazis came to power in 1933 and quickly began a mass antisemitic persecution, looting their businesses, consigning them to overcrowded ghettos, and eventually exterminating 6 million Jews.

After the Nazis enacted the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, Adler was forced to give up his position at the leathermaker, and with citizenship stripped of Jews and brutal antisemitic violence a regular occurrence, the family started plotting how it could escape Germany. That was complicated by Germany’s ruinous “flight tax” on the assets of emigrants, “a powerful instrument for stripping Jews of their assets” according to Bennigson.

The family fled Germany in June 1938, voyaging through the Netherlands, France, and Switzerland as they sought to permanently emigrate to Argentina. The Adlers, in short order, needed funds to obtain a visa and emigrate to South America, but faced the quandary of having to declare their funds to be transferred out of Germany, subjecting them to flight taxes.

And so, in October, Adler sold “Woman Ironing” to Thannhauser’s son, Justin, for a measly $1,552, about $33,000 in 2022 dollars. That “far below market value and less than one ninth of his asking price in 1932,” according to the suit.

“Thannhauser, as a leading art dealer of Picasso, must have known he acquired the Painting for a fire sale price,” reads the suit. “At the time of the sale, Thannhauser was buying comparable masterpieces from other German Jews who were fleeing from Germany and profiting from their misfortune. Thannhauser was well-aware of the plight of Adler and his family, and that, absent Nazi persecution, Adler would never have sold the Painting when he did at such a price.”

The Adlers finally boarded a ship to Buenos Aires in April 1940; the Nazis would ultimately loot all that was left of Adler’s assets. Jacobi died in 1946 and Adler in 1957; they were survived by their three children: Carlota, Eric, and Juan Jorge.

As assets were violently stripped of Adler and other Jews, Thannhauser quickly sought to flip the painting while hiding the shady provenance of its acquisition. In 1939, he loaned the masterpiece to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and later New York’s Museum of Modern Art; MOMA insured the painting for $25,000, sixteen times what Thannhauser paid Adler for it. In 1963, Thannhauser agreed to bequeath the painting to the Guggenheim upon his death; the Guggenheim has possessed the work since 1978.

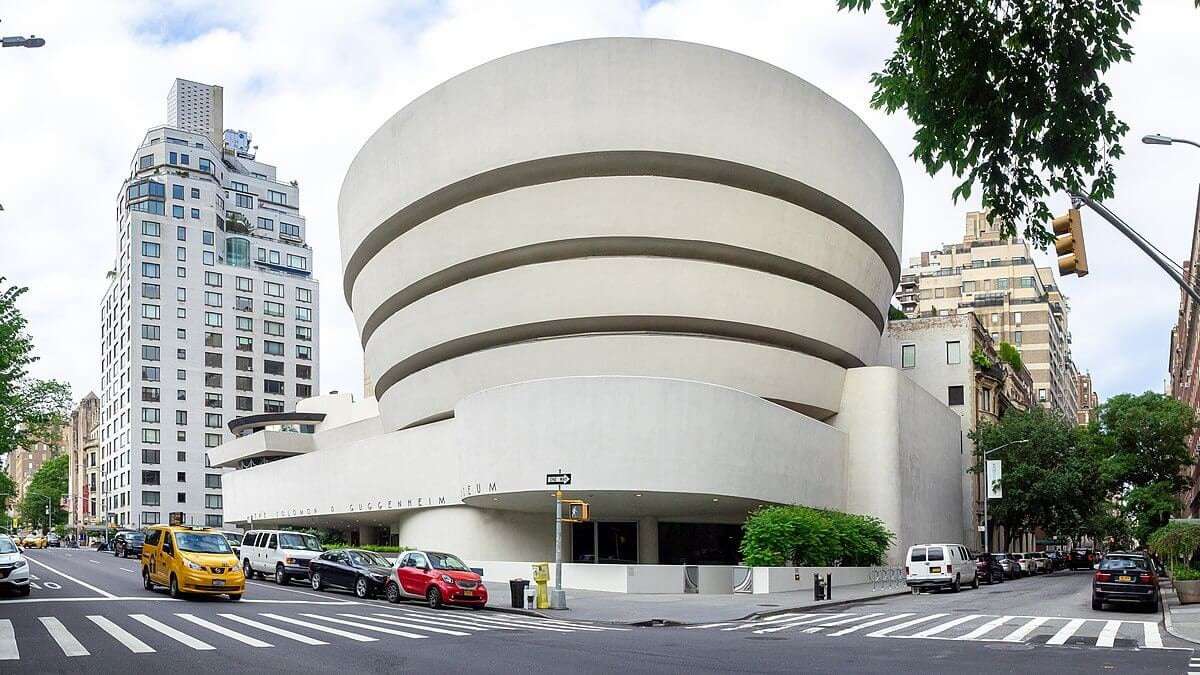

The family learned it may have once owned the artwork in 2014, and in 2017 their lawyers contacted the Guggenheim; in 2021, they demanded its repatriation, citing the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act passed by Congress in 2016. The Guggenheim has refused to entertain the demand, says Bennigson, and it remains in the Upper East Side museum’s possession.

In a statement, the Guggenheim said the family’s claims were “without merit.”

“The Guggenheim takes provenance matters and restitution claims extremely seriously,” said Sara Fox, the museum’s communications director. “The Guggenheim has conducted expansive research and a detailed inquiry in response to this claim, engaged in dialogue with claimants’ counsel over the course of several years, and believes the claim to be without merit.”

The museum seeks to distinguish the painting from other works of art stolen by the Nazis, noting instead that “Woman Ironing” was sold to a gallery owner already known to Adler, and Thannhauser himself faced sanction by the Nazis as they attempted to root out “degenerate” avant-garde art.

Guggenheim honchos even reached out to the Adlers’ son Eric, then living in New York, in the 1970s to interview him about the painting’s provenance, and say that he raised no concerns at the time. “Woman Ironing” has remained on public display at the Guggenheim ever since.

“It is unclear on what basis claimants — more than 80 years after Adler’s sale of Woman Ironing — appear to have come to a view as to the fairness of the transaction that neither Karl Adler nor his immediate descendants appear to have ever expressed, even when the Guggenheim contacted the family directly to ask,” said Fox. “The facts demonstrate that Karl Adler’s sale of the painting to Justin Thannhauser was a fair transaction between parties with a longstanding and continuing relationship.”

Art looted by the Nazis is worth billions of dollars today. After World War II, the US government estimated the Nazis stole an incredible 20% of all the artwork in Europe; much of that art still has not been returned to its rightful owners.

Last year, New York State passed a law requiring all museums to prominently acknowledge whether art on display “changed hands due to theft, seizure, confiscation, forced sale or other involuntary means” as a result of Nazi persecution. The Guggenheim and MOMA were allowed to keep art obtained by the Nazis after settling in 2009 with Julius Schoeps, whose great uncle was forced to sell Picasso’s “Boy Leading a Horse” and “Le Moulin de la Galette.”

gopoohgo on January 23rd, 2023 at 15:40 UTC »

This is a less cut and dry case than people in this thread are making it out to be, especially if the Guggenheim has documentation of their interactions with a direct heir 50 years ago.

jordanosa on January 23rd, 2023 at 14:18 UTC »

This seems like something that should’ve probably been resolved… decades ago?

Jyorin on January 23rd, 2023 at 12:42 UTC »

They museum said they reached out to a relative in the 70s, and that relative wasn’t concerned about the painting. Can the family still try to claim it? Serious question.

Like… say I were Jewish and this happened, but my mom was like… “I don’t care about this item.” Can I or my kids honestly try to reclaim it 50 years later? Even with the duress and restitution act, because my mother rejected it, I’d get nothing, right? If that’s the case, I’d think it’s fair… damn sure wouldn’t be happy about it. But if they were never offered such a chance, can they seriously expect $200m? I would think that’s ridiculous considering almost valuables from back then would clearly be worth way more now. Since the piece was given to the museum, are they responsible for paying that amount?

I need answers. This is actually pretty interesting.