Their challenge: Making the public care deeply — and read hundreds of pages more — about an event that happened more than a year ago, and that many Americans feel they already understand.

They’ll attempt to do so this spring through public hearings, along with a potential interim report and a final report that will be published ahead of the November midterms — with the findings likely a key part of the Democrats midterm strategy. They hope their recommendations to prevent another insurrection will be adopted, but also that their work will repel voters from Republicans who they say helped propel the attack.

Democrats are widely expected to have a tough time in the upcoming midterm elections, with even some Democrats privately fearing a bloodbath.

Looming over lawmakers are a handful of high-profile government reports — some more recent than others — that provide a laundry list of lessons learned as the committee deliberates the best way to present its findings: the Senate Watergate Report, the 9/11 Commission Report, and special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s report on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election.

Much to the frustration of Democratic lawmakers at the time, Mueller’s lawyerly and heavily redacted 400 page report conspicuously excluded an explicit recommendation that former president Donald Trump be prosecuted for obstruction of justice for allegedly interfering with the inquiry.

While the Jan. 6 committee’s mandate fundamentally differs from Mueller’s task, it’s seeking to avoid the challenges the special counsel created for Democrats in translating his dense report to the broader public — and employing it as a tool to bolster support for impeachment proceedings against Trump.

Committee staffers have interviewed writers to assist with the herculean task of quickly turning around hundreds of thousands of pages of depositions, records and other evidence into an accessible narrative, according to people familiar with the conversations. Staffers have asked those writers about their deadline experience, thoughts on how the report should be structured and how they would manage strong personalities pushing for their piece of the pie to be included, according to people familiar with the interviews.

It’s unclear whether the committee will succeed in bringing on a high-profile journalist or if the committee has finalized a choice to author the report. But the committee’s leaders are keenly aware of the difficulty in breaking through to hard-to-reach audiences, according to staffers and members involved in the process.

“We do not want a bureaucrat to write this report but rather a historian or a journalist — or someone who writes and can tell a story in a compelling way so that people can actually understand what happened,” said Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-Fla.), a member of the committee.

Two people with knowledge of the report say the committee wants it to include gripping testimony and quotes, along with starring roles for key players in the events leading up to and on Jan. 6, 2021.

Rep. Peter Aguilar (D-Calif.), who has been steeping himself in reports issued by congressional investigations throughout history, told The Washington Post in an interview that the committee is committed to ensuring that the report isn’t written in “Congressional Research Service” style.

“Representing people of color and young people, I’m acutely aware of how they will process this work,” Aguilar added.

The committee has discussed the potential for criminal referrals should it produce enough evidence to support those findings. But unlike the Mueller report, the Jan. 6 committee’s narrative work will not be bound by the same constraints faced by the Justice Department in trying to decipher what acts of criminal liability it could prosecute — giving them more room to produce compelling reading.

“The role Congress has asked the Jan. 6 committee to play is one that’s much more focused on the moral responsibility, the corruption of power, and abuse of regular order that the Trump administration engaged in during those final weeks leading up to the insurrection,” said Garrett Graff, a journalist and historian who has authored books on Sept. 11 and Watergate.

“The Justice Department might decide that Trump is not criminally liable for his actions but that the committee is able to provide at least a high standard of proof that Trump was morally liable — and as a political question that latter standard is, in some ways, more important to the future of the country than the criminal ones,” Graff added.

The 9/11 Commission Report, formally named the “Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States,” became one of the best-selling government reports in American history, lauded for its narrative power and accessible writing. The report successfully pulled together thousands of interviews, 570 cubic feet of records, countless findings and extensive recommendations into a final piece of writing that read like a novel.

The committee has already met with individuals involved with the 9/11 commission, including its executive director, Philip D. Zelikow, who declined an interview with The Washington Post.

“I’ve had the chance to give my two cents to people who are working on this,” he wrote in an email.

Jamie Gorelick, a member of the 9/11 commission, said she met with the committee at the outset of the investigation and provided three central recommendations. In a meeting that also included Tim Roemer, another member of the 9/11 commission, Gorelick advised investigators and lawmakers to write the report in an accessible way; not to rush into hearings without sufficient findings; and to “build the case from the bottom up.”

Committee member Rep. Jamie B. Raskin (D-Md.) “was most interested in that: how do we make the report tell a story? How do you take the different pieces of the story that are produced by a very large group of people and make it sing? And I think that’s very much what they would like to do,” said Gorelick of her discussion with the committee.

Gorelick added that the 9/11 commission’s work benefited from the commitment from victims’ family members, and said the committee would be wise to highlight the stories of law enforcement officials and those impacted by the insurrection to “bring home the consequence” of the day.

Unlike the Jan. 6 committee, however, the public broadly supported and approved of the work of the commission in investigating the events that led to the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Lawmakers are mindful of the challenges in breaking through to deeply polarized audiences. The ideological hurdles the committee faces in communicating with the broader American public have only intensified since the committee’s inception, as Republicans have sought to downplay the attack on the Capitol.

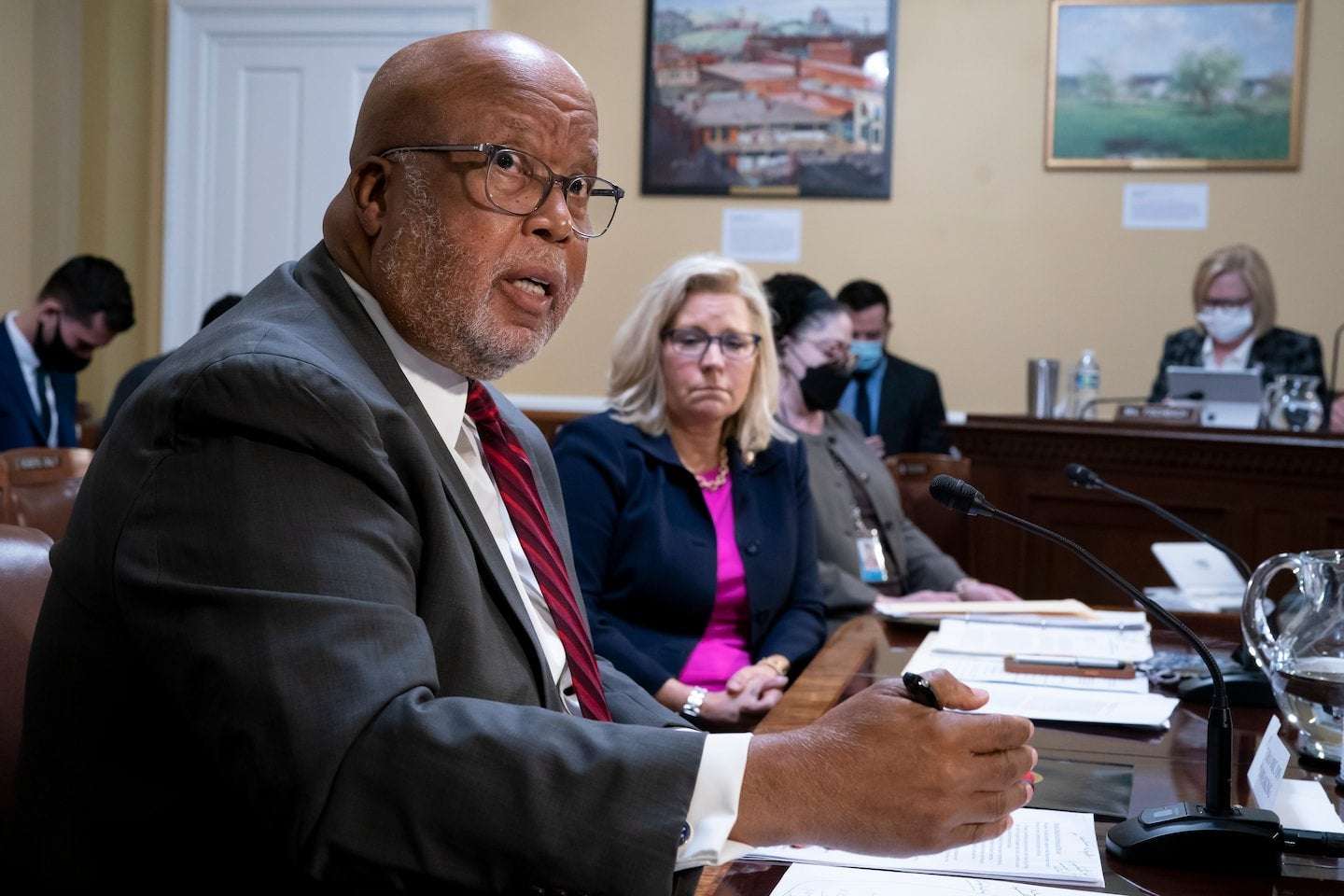

While two Republicans are serving on the committee — Reps. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) and Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) — House Republicans and conservative media have sought to assail the committee and Cheney and Kinzinger’s party credentials. Cheney has extensively talked about the committee’s work, spending the majority of her time on the matter, people familiar with her work say.

The GOP’s campaign to discredit the committee’s work has found some success: a Washington Post-University of Maryland poll conducted earlier this year found that Democrats and Republicans are deeply divided over the events that occurred that day and the degree to which Trump is culpable.

The poll found 54 percent of Americans who characterize the protesters who entered the Capitol as “mostly violent,” and broken down by party, 36 percent of Republicans says the protesters were mostly peaceful.

“There’s one-third of the nation that will read it, one-third that might read it, and one-third that won’t even believe it,” said a committee lawmaker, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak candidly. The lawmaker added that even some of their Democratic constituents have lost interest in the committee’s work because of more pressing issues, like inflation and the coronavirus pandemic. “So it’s key to tell the best story possible with the report that is ultimately issued by the committee so that it actually breaks through.”

But Celinda Lake, one of President Biden’s top 2020 pollsters, said that she has seen a shift in sentiment in focus groups over the past six months toward the committee’s work.

“We’ve seen a shift among voter feeling like this was a one time deal and we need to move on, to feeling like we need to make sure this never happens again … And I think the hearings will make it even more salient,” Lake said of the Jan. 6 insurrection. “I suspect that two thirds of the voters are going to be weighing: did something happen here that I should be paying attention to? And are current elected officials doing current actions that I should weigh in my vote and are their past actions that I should weigh in my vote?”

As it currently stands, the committee’s timeline has been pushed back as it races to wrap up depositions and interviews with individuals due to ongoing litigation that has delayed records requests. Chairman Bennie G. Thompson (D-Miss.) recently told reporters that public hearings are expected to commence in May and that the deadlines for the interim and final report are also influx.

“It’s a moving target,” said Thompson. “We have some timetables but when we get 10,000 pages of information that we need to go through, the timetable moves.”

The committee is expected to hold a retreat once interviews have been completed in order for investigators to get lawmakers up to speed on the deluge of information they’ve collected thus far before moving to the public phase, according to people familiar with the planning.

The public hearings might prove to be the committee’s best opportunity to fulfill their explanatory role and reach audiences outside the Beltway with well-produced, viral moments. Graff said the committee would be wise to reference the 1973 televised Senate Watergate hearings that broke down a complex story in ways the public could actually understand, sparking prolonged and intense media coverage.

At the time, Majority Counsel Sam Dash’s strategy was to build a case before hearing from star witnesses. For example, much of the first hearing on May 17, 1973 was dedicated to understanding how the Nixon White House was organized. Bruce Kehrli, a special assistant to Richard M. Nixon, walked investigators through an organizational chart and showed investigators who reported to H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, two of Nixon’s top aides who were ultimately sentenced to prison for their role in the Watergate coverup.

“This is a story that fundamentally the American people don’t understand and it’s one where there are a lot of players,” said Graff, referring to the Jan. 6 attack. “So I think that one of the things that the committee should be trying to think through is not just going for the splashiest headline that they can but instead trying to tell a coherent story.”

The committee is also competing for attention amid a flurry of current events that now includes the war in Ukraine, raising the stakes for the committee’s ability to hold the public’s attention as the insurrection moves further and further back from in public memory. Don Ritchie, historian emeritus of the Senate, said that the most important thing for any congressional committee is publicity.

“Investigators need a certain sense of showmanship — they really need to demonstrate and dramatize what’s happening because the public is distracted,” said Ritchie. “After getting the publicity, then it’s figuring out what you’re actually going to do about the problem.”

There can be trade-offs, however, when it comes to balancing how to entice people to provide public testimony versus ensuring that someone who has committed a crime ultimately goes to jail. For example, a federal judge threw out the case against retired Marine Corps Lt. Col. Oliver North after he testified under a grant of immunity from prosecution in the 1987 Congressional investigation of the coverup of the Iran-contra arms-for-hostages scandal.

But the value of the potential for discovery during public testimony is paramount. It wasn’t until mid-July — two months after the start of the Watergate hearings — that Alexander Butterfield, a former White House aide to Nixon, revealed the existence of recording devices in the Oval Office and bugged telephones.

DMs_Apprentice on March 18th, 2022 at 14:40 UTC »

I don't understand what the public caring has to do with holding them accountable for their actions. People don't care that someone was smoking weed, but doesn't stop the cops from throwing them in jail, does it?

m1j2p3 on March 18th, 2022 at 12:45 UTC »

If Trump and his criminal cronies get away with their crimes then the only conclusion I can come to is the rule of law does not exist in the United States. There is no other option. The law either applies to them, just like it would apply to me, or the law doesn’t really exist.

Prove that we are a nation of laws and let justice be brought to these criminals.

Kebb on March 18th, 2022 at 12:37 UTC »

You want me to care, prove to me you plan to hold these traitors accountable.