As another dramatic year comes to a conclusion, we at Encyclopedia Geopolitica expect that 2022 will continue to provide challenges from the geopolitical perspective. The great powers will continue to challenge one another, populations will test their governments, and the pandemic will likely continue to put pressure on already-present geopolitical fault lines. In this annual piece – which supplements our regular geopolitical book reviews – we put forward our list of suggestions for those seeking to better understand the coming year’s geopolitical movements, including academic textbooks, historical studies and insights from some of the world’s greatest geopolitical minds.

Disclosure: Purchases made using the links in this article earn referral payments for Encyclopedia Geopolitica. As an independent publication, our writers are volunteers from within the professional geopolitical intelligence community, and referrals like this support our ability to create future content by funding server time and domain fees.

As this list contains a large effective way to get through the reading list. Encyclopedia Geopolitica readers have access to a 30-day free trial for Kindle Unlimited, allowing them to sample over 1 million ebooks and thousands of audiobooks.

While our annual reading list is divided into thematic sections (see below), the analyst team at Encyclopedia Geopolitica have also put forward a collection of their personal recommendations to start the list.

We Are Bellingcat (2021) – Eliot Higgins

For those not familiar with the organisation, Bellingcat is a collective of amateur open source intelligence investigators that seeks out war crimes, abuses of power, and other repressive actions by states around the world. Released earlier this year, Higgins’ book is ostensibly the history of “The People’s Intelligence Agency”. The book is something more profound than that, however, and is highly relevant to current geopolitics. Higgins explores the Russian disinformation machine, along with those of other states, to explore how the truth now seems a less tangible concept than ever before. For those seeking to understand the phenomena of misinformation will wish to combine this book with others such as Active Measures, Manufacturing Consent, and LikeWar to understand the silently-raging Information War we currently find ourselves in. Higgins provides a perfect guide, given his role on the front lines. This book is recommended for all students of geopolitics seeking to understand the modern information landscape.

Why Spy? (2015) – Brian Stewart and Samantha Newberry

Stewart and Newberry take us on a tour through the value of intelligence and its relevance to decision-making, set against the backdrop of a century of global events. This book is an excellent introduction to the concept of intelligence, and offers it with clear geopolitical framing. While the book is coloured heavily by Stewart’s own experiences during the Malayan emergency, a comparative assessment of the US engagement in Vietnam allows the reader to understand the different ways of fighting an insurgency through intelligence-led warfare. With this year’s unsurprising-yet-frustrating withdrawal from Afghanistan, these are lessons that ought to be kept close at heart by all students of geopolitics.

Going Dark: The Secret Social Lives of Extremists (2021) – Julia Ebner

A tremendously courageous piece of work, driven by several years spent undercover in various extremist communities both online and in-person, Going Dark takes the reader on a tour of the various hardcore communities that have multiplied in the modern social-media-driven world. Ebner explores the radicalisation pathways that can lead an individual to join a plethora of groups, ranging from the Islamic State, Generation Identity, the Incel and Tradwives movements, and others, and how many of these individuals resemble one another despite their polar opposite belief systems. With the arc of counter extremist governance shifting away from an over-focus of Islamic extremism, this book is an excellent introduction to the landscape of extremist communities and how they are formed, and is of particular interest to students of terrorism and radicalisation.

The War of Words: A Glossary of Globalization (2021) – Harold James

The language of geopolitics has in recent years begun to take on a particularly politically-charged tone, with casual misuse and misapplication of terms becoming increasingly common. Words such as “Socialism”, “Neoliberalism”, “Capitalism”, and “Populism” have been thrown around inappropriately by politicians and political commentators alike. In this highly timely book, Princeton professor Harold James takes us through the origins and definitions of political terminology. James argues that the increasing vagueness of terminology is making communication across political divides increasingly more difficult, and that establishing a common glossary of political language is critical. This book is crucial reading for all students and observers of politics.

Risk: A User’s Guide (2021) – Gen Stanley McChrystal (ret)

This book is an insightful masterclass in understanding, managing, and responding to risk written by the former commander of ISAF and US forces in Afghanistan. Whilst it does examine the well-understood numerical ideas of probability in risk, it focuses on the all-important human aspect about how leadership can identify, manage, and communicate risk. This book will make you a better analyst, but it may also make you a better leader.

The Ledger: Accounting for Failure in Afghanistan (2021) – David Kilcullen and Greg Mills

The calamitous failure in Afghanistan this year has been compared to the Fall of Saigon so many times it is already becoming a hackneyed cliché. In reality, the failure was in many ways worse than that in Vietnam, and the consequences could well be more dire. There is no issue today more warranting a national autopsy to understand how we got here, why, and what to do about it to ensure that past mistakes are not also future mistakes. Few people are better qualified to wield the scalpel as part of that autopsy than David Kilcullen, a counterinsurgency expert who has advised the US Government on its approach to Iraq and Afghanistan and even wrote the manual for dealing with ISIS. Despite his participation in the campaigns, Kilcullen’s analysis is clear-eyed and full of humility, this book is not an exercise in delusional self-justification or hand-wringing excuse-making. It explains clearly the political landscape throughout the conflict, the successes and failures had along the way, and the reasons that it concluded in the way it did. Further, it makes a number of prescriptions for the future, which any analyst worth their salt would do well to read and digest.

Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea (2017) – Shiraz Maher

Although much of the world has begun to pivot away from violent extremism and terrorism in favor of great power competition and the geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific, this would be a bit of a deception. Throughout these theaters, whether they be in India, China, or Southeast Asia, there are many political and social undercurrents that remain despite these great power plays. As 2021 has shown, organizations like the Afghanistan Taliban and Jemaah Islamiyah continued to be significant players that should not be discounted or underestimated. As such, Shiraz Maher’s Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea remains ever prevalent. Maher does an amazing breakdown of the origins of Islamist extremism and dives into many core concepts that one should understand when trying to assess these groups. His book highlights concepts like al-wala wa al-bara, the notion of Tawhid among Salafis, and other key points. For those looking for a deeper understanding of this particular ideology, then Shiraz Maher’s work is an absolutely fantastic read.

Beirut Fragments: A War Memoir (2004) – Jean Said Makdisi

The situation in Lebanon has greatly deteriorated. After the 2021 August port explosion, the Lebanese economic system took a nosedive, with inflation rapidly expanding. In consequence, many Lebanese individuals have taken flight, leaving their country for places abroad in Europe, the Americas, and elsewhere. However, the problems facing modern Lebanon have historic precedence, heralding from poor government management throughout the 2010s, a lack of major structural reforms in the 2000s, and the Lebanese Civil War of 1975-1990. Beirut Fragments: A War Memoir is a personal account by Jean Said Makdisi about her time during that civil war. It is a telling and harrowing narrative that explores the devastation Lebanon faced in the time, while also highlighting the factors that would ultimately give rise to the modern and failing state. Makdisi’s are poignant but also informative, and highlight the horrors that many faced during the Lebanese Civil War. As a piece of contextual history that illuminates on the present, Makidisi’s memoirs are a powerful read.

Rethinking Chinese Politics (2021) – Joseph Fewsmith

In Rethinking Chinese Politics veteran China watcher and Chinese Communist Party expert Joseph Fewsmith lifts the lid on the black box of elite Chinese politics. Fewsmith traces the promotions, alliances and relationships that led to the post-Mao leaders taking (or being given) power, and how they struggled to consolidate it, often against the will and interests of their predecessors. The author outlines how conventions put in place by Deng attempted to institutionalise power but which, while not ineffectual, still led to Jiang and Hu struggling against the influence of their predecessors. Fewsmith shows how China’s leaders have had to build from positions of initial weakness to secure their power and influence. A central question addressed by the book is whether the CCP has reformed and institutionalised itself as many observers seem to think or is it, as he argues, still a fundamentally Leninist organisation that resists institutionalisation, where relationships and personal power define the structure rather than established norms and institutions.

While not a barn-burning page-turner, and best approached with at least some knowledge of China’s late 20th century political history, Rethinking Chinese Politics is an interesting read and a useful reference for the careers of senior CCP figures, it should also be read by any aspiring analyst of Chinese politics. It is particularly prescient as we enter 2022, when Xi Jinping is expected to break yet another norm and seek a third term as president.

The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World (2020) – S. Jaishankar

Written by the current Minister of External Affairs of India, this book provides a window into the mind of the career diplomat that has helmed the Indian foreign policy establishment since May 2019. The book lays down quite succinctly the possible options India has at its disposal as the world transitions to a multi-polar order. The book was composed by the author ‘through a series of events,’ mostly from different lectures given by Dr. Jaishankar himself. It thus reads like a collection of essays or personal thoughts instead of a concrete action plan or doctrine. Dr. Jaishankar also employs plenty of historical metaphors and borrows from Indian tradition (most importantly Chanakya) to put forth his points and arguments. To conclude, this book is a must-read for anyone trying to understand how a changing and more confident India is beginning to see itself in a post-cold war world.

The Places in Between (2014) – Rory Stewart

In keeping with my tradition of rarely reading geopolitical books I thought I would recommend a book that, given the events in Afghanistan, remains profound; The Places In Between by Rory Stewart. Foreign Office, Army Officer, Member of Parliament. His list of jobs reads like a Boys Own adventurer, and indeed this book is in keeping with the theme. Rory Stewart walks across Afghanistan mere weeks after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, taking advantage of the power vacuum to complete a walk that took him over much of Asia. Rory Stewart blends observation with a powerfully understated commentary on the people he moves amongst. Plus he adopts a dog. Therefore truly this is a book for everyone. On a serious note, this book is a snapshot of an Afghanistan on the brink: of a future unrealised and a fear of the unknown. A moment as relevant in 2021 as in 2001.

Eamon Driscoll – Russia and Former Soviet Spaces Analyst

Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia (2021) – Timothy Frye

There is a quote, attributed to a number of different statesmen, that Russia is neither as strong nor as weak as she appears. Yet recently, most media attention on Russia concerns the man who has been at the helm of the Russian ship of state for more than two decades (glossing over a brief intermission). Vladimir Putin, the bogeyman of the West, is a reflection of this quote. In this marvelous read, Frye analyses how accurate the portrayal of Putin actually is, and digs deep into the Russian reality to find the truth of Putin’s grip on power at home and his ability to project his will beyond the borders of the Russian Federation.

The Cold War, the Space Race, and the Law of Outer Space: Space for Peace (2021) – Albert Lai

Throughout history, as human Civilization has expanded and spread its influence, conflict over resources is the standard. And where there has been conflict, there has been law to set the rules of the competition. As humanity has had a taste of what lies beyond the blue skies, and now looks to what may come for colonisation and exploitation of other worlds, law is going with us. Whether these worlds are using for the common benefit of mankind or old habits of competition set in, the parameters of the coming Second Age of Exploration have already been established. Lai goes in depth to thoroughly explain how we got to where we are now in setting the rules for space, and lays the foundation for the hope of humanity united in our wonder and excitement for the worlds to be found beyond our island Earth.

Agents of Influence: Britain’s Secret Intelligence War Against the IRA (2021) – Aaron Edwards

Aaron Edwards provides a detailed account of the strategy behind the British intelligence-led fight against Irish republicanism during the height of the Troubles. This book reveals a gripping divergence between the raw tradecraft of field operations and the strategic expectations that were shaping the war from afar. Bringing to light how British agents infiltrated all levels of the PIRA, this book offers a shocking glimpse into the brutal and contentious challenges that influenced and shaped the fragile peace process that exists today. Lessons on institutional intelligence cooperation, tactical adaptation, and human psychology are all to be found within Edwards’ work.

This year has seen the Covid-19 pandemic continue to put extreme pressure on governments, corporations, societies, and the links that hold them together. There have been positive developments, most notably in the form of rapid rollout of vaccines, but also worrying changes, such as the discovery of the new Omicron variant, on which data is still emerging. Against this backdrop, the world has witnessed a number of major flashpoints as well as events which will have greater impact in months and years to come.

Numerous politicians left office in a plethora of ways. After a tense start to the year, following the storming of the Capitol, Donald Trump left the White House to make way for Joe Biden, who has set out a strategy of reversing many Trump-era policies and re-engaging with the international community, although not to the degree the USA had under Barack Obama. Aung San Suu Kyi, the erstwhile darling of global human right movements, was unceremoniously removed from office in a military coup and sentenced in a kangaroo court to four years in prison. This ended her 5-year reign as State Counsellor during which she was stripped of her Nobel Peace Prize for her failure to address the genocide being carried out against the Rohingya population. A coup d’état took place in Mali, the second in nine months, causing France to withdraw its support for Operation Barkhane, which is likely to lead to a jihadist resurgence in the Maghreb. Coups also took place in Guinea and Sudan, with the military in both taking control. In Guinea the military has pledged to hold elections, in which nobody who participated in the coup will be allowed to stand, offering some reassurance that a return to civilian life might be achievable. In Sudan, a turbulent two years since the initial coup which removed long-serving President Bashir from power culminated in protests demanding a further coup. Whilst this took place, the original government was restored after a number incidents led to military personnel opening fire on protesters. A 14-point plan was agreed, which allowed the previous government to return to office, but has left both the civilian government and the military damaged and needing to re-establish credibility with the public. The results of these coups in Africa remain to be seen and the full ramifications will not be felt until 2022 and beyond. Iran’s President Rouhani left office having served his term limit, and Iran’s new President is a familiar face. Ebrahim Raisi is a close ally of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei and previously served as Chief Justice, among other senior posts. He was instrumental in the purges of the 1980s, which saw thousands of political prisoners tortured to death and executed without trial. He is an extreme hardliner with a greater antipathy to the West than Rouhani, which presents major challenges to President Biden in resurrecting the nuclear deal. Since taking power he has already reinstituted uranium enrichment, raising the spectre of a ‘breakout’ nuclear capability, which is causing increasing concern in Israel, who are considering their next moves to head off an Iran with the Bomb.

2021 saw the beginning of shifts in three major powers who have been mainstays on the world stage for decades. Angela Merkel handed the Chancellorship of Germany to Olaf Scholz after 16 years serving not only as Germany’s leader, but also the person who held the European Union together and oversaw a period of relative stability, despite numerous shocks and crises. Whether Scholz continues Germany’s key role in the EU, or whether he cedes the position to other European leaders such as Emmanuel Macron remains to be seen. Japan also elected a new Prime Minister after a successful Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo, having been postponed for a year by the pandemic. Shinzo Abe’s initial successor Yoshihide Suga was unable to convince colleagues or the nation of his competence in his handling of the pandemic and announced that he would not be seeking the Premiership again less than a year after taking office. Kishida has big shoes to fill, but is likely to take a slightly direction than Abe had envisioned. He is more dovish on foreign policy and sees Japan’s rearmament and abandonment of pacifism with ambivalence. He has stated he aims to moderate Japan’s ‘Abenomics’ model to address inequality and may well impose greater levels of regulation on the economy. Benjamin Netanyahu, after a total of 15 years as Israel’s Prime Minister (across two terms), making him the country’s longest-serving leader, was removed from office following four inconclusive general elections since 2019. He is replaced by Naftali Bennett, who was able to agree a rotational arrangement with Yair Lapid, meaning they will each serve two years as Prime Minister, providing the Government can last that long. Israeli politics is complicated and requires careful negotiation at the best of times, but the current government remains precarious as its constituent factions begin to realise they disagree on more than they first thought, from amending Israel’s citizenship law, to the ultra-orthodox Haredim’s participation in the national draft to – crucially – meeting with Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas. Shortly before Netanyahu’s departure, another flare-up in tensions with the Palestinians, as rockets were fired from Gaza and met with airstrikes. Whilst the Government has changed, the Palestinian issue looks no closer to being resolved.

A number of high-profile killings took place, from the murder of the Italian Ambassador to the Democratic Republic of Congo in a botched kidnapping attempt on a World Food Programme convoy, to the assassination of the President of Haiti, to the death of Chad’s President Idriss Déby in clashes with rebels. The full geopolitical ramification of these have not yet been felt and the impacts on international aid to the DRC, the choice of the next Haitian and Chadian leaders, and the part Chad plays against the backdrop of the Islamist insurgency in the region, remain to be seen. Key international agreements have entered into force. The African Continental Free Trade Area has been created, with high hopes for reducing both poverty and inequality, potentially unleashing a dormant economic giant who has been sleeping for centuries. The Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons is now in place, with 86 signatories, including regional powers Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, and Nigeria. The G7 global minimum corporate tax rate was agreed at 15%, an international effort to tackle tax avoidance. The situation in Tigray, Ethiopia continues to escalate as the civil war which began in November 2020 shows no signs of ending, with war crimes being carried out on all sides of the conflict and a deeply troubling humanitarian crisis developing. Kenya, Niger, Tunisia, and St Vincent and the Grenadines set up the African 3+1 group (A3+1) to try to mediate and have called for an ‘Ethiopian-owned’ peace process to resolve the issues and build towards peace.

As well as new agreements being struck, the USA under Biden re-entered the Paris Climate Accords, moving the world closer to the necessary, meaningful actions to address climate change and avoid global temperature increases of more than 1.5 or 2 degrees. Weather events including a hurricane in New Orleans, 16 years after Hurricane Katrina ripped through the city; a winter storm in the US which killed 136 people and caused an energy crisis in Texas; over 130 wildfires in Canada; major flood events in Central and Eastern Europe and south India, and an earthquake in Haiti underscored the urgent need to make progress. Turkey pulled out of the Istanbul Convention, which is a Council of Europe agreement on women’s rights. Whilst it appears the USA is at least partially rejoining the international community and its responsibility for global governance, Turkey seems to be backsliding every further towards authoritarianism and away from the West.

Much to the chagrin of French President Emmanuel Macron, a defence partnership between the USA, UK, and Australia, called AUKUS for short was announced, which included dumping an Australian contract for French submarines in favour of American and British submarines instead. This new partnership reinforces the UK and USA’s tilt to the Asia-Pacific region and buttresses Australia against Chinese aggression. France responded by bolstering its relationship with the Emiratis, agreeing a $19bn arms deal for French Rafale fighter jets.

The fragility of the global logistics system has been laid bare, after the Evergiven blocked the Suez Canal, causing chaos in world shipping. The Evergiven is not the only factor and global shortages in haulage drivers and rising fuel costs amid other political and practical will see 2022 grappling with increasing strain on the systems that supply key goods and services. From Evergiven to Evergrande, the Chinese property giants travails have led to financial shocks around the world and a property bubble at home, which has not resolved by the end of the year – this could be an issue that leads to further economic crisis in 2022.

Russia continues to make mischief on the world stage, using the pandemic to consolidate de facto power over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh/Artsakh region. It is also increasing its presence and activity in the Arctic as climate change creates new naval and commercial opportunities. Perhaps most importantly, increasing troop build-ups at the Ukrainian border mean that we could open 2022 with an early invasion as Russia becomes ever more assertive towards its neighbour. Belarus continues to be a running sore as the last dictatorship in Europe, as Belarusian military jets forced a commercial airliner to land in Minsk to arrest journalist Roman Protasevich. Following the Olympics, sprinter Krystina Tsimanouskaya sough political asylum in Poland after Belarus attempted to repatriate her by force. Tensions continue to rise at the Polish border, with Belarus accused of conducting hybrid warfare by attempting to send thousands of illegal migrants across, bringing them into conflict with the European Union.

After fighting a ten-year war, it appears the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has all but won his battle with the Free Syrian Army, ISIS and other opposing factions, but has so far failed to re-establish full control of the country. The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continue to hold territory administered by the Autonomous Administration of North East Syria, in which over 10,000 ISIS fighters and their families are still being held in increasingly poorly-guarded camps, raising the spectre of an ISIS resurgence. Turkey is also occupying its ‘security buffer’ zone in the north of the country, with its Syrian National Army proxy force continuing to wage war against the SDF.

Of course, the largest international event in 2021 was the dramatic withdrawal of American and Coalition troops from Afghanistan and the rapid advance of the Taliban, who captured Kabul within a matter of weeks. This was followed by a suicide bombing at Kabul airport, killing at least 182 people, including 13 American service personnel, and an American drone strike that killed 10 civilians. The West has no appetite for further ‘boots on the ground’ interventions, but neither is it rushing to recognise the Government. Whilst Western troops have gone home, the international situation in terms of relations with Afghanistan has not been settled, and domestically the Taliban has reinstituted many of its rules from the ‘90s, raising major humanitarian concerns, particularly over womens’ rights and the treatment of minorities.

All in all, it has been a dramatic and strange year that has showcased as ever that the only true continuity in international affairs is change. Our reading list is shorter this year, following a decision to focus on quality over quantity, but we hope it gives you plenty of recommendations for improving your knowledge of the key issues and countries that could shape future history as we enter 2022 and the third year of coming to terms with Covid-19.

“Aftershocks: Pandemic Politics and the End of the Old International Order” (2021) Colin Kahl & Thomas Wright

“The End of Epidemics” (2018) Dr Jonathan D. Quick

“Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic” (2013) David Quammen

“The Great Covid Panic: What Happened, Why, and What To Do Next” (2021) Gigi Foster, Paul Frijters, and Michael Baker

“Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19” (2021) Alina Chan and Matt Ridley

“The Vaccine: Inside the Race to Conquer the COVID-19 Pandemic” (2021) Joe Miller, Ugur Sahin, and Ozlem Tureci

“Vaxxers: The Inside Story of the Oxford AstraZeneca Vaccine and the Race Against the Virus” (2021) Sarah Gilbert and Catherine Green

“The Pandemic Century: A History of Global Contagion from the Spanish Flu to Covid-19” (2020) Mark Honigsbaum

One to watch: “COVID-19 in Southeast Asia: Insights for a Post-Pandemic World” (2022) Hyung Ban Shin, Murray McKenzie, and Do Young Oh (Eds)

“Chaos Under Heaven: Trump, Xi, and the Battle for the Twenty-First Century” (2021) Rogin Josh Rogin

“The Great Decoupling: China, America and the Struggle for Technological Supremacy” (2020) Nigel Inkster

“China’s Asian Dream: Empire Building along the New Silk Road” (2019) Tom Miller

“The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics” (2020) Andrew Small

“China’s Western Horizon: Beijing and the New Geopolitics of Eurasia” (2021) Daniel Markey

“Lee Kuan Yew: The Grand Master’s Insights on China, the United States, and the World” (2020) Graham Allison

“Destined for War: can America and China escape Thucydides’ Trap?” (2018) Graham Allison

“The World According to China” (2021) Elizabeth Economy

“The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia” (2019) Ian Easton

“The War on Uyghurs: China’s Campaign Against Xinjiang’s Muslims” (2021) Sean R. Roberts

“Understanding Afghanistan: History, Politics and the Economy” (2021) Abdul Qayyam Khan

“Midnight’s Borders: A People’s History of Modern India” (2021) Suchitra Vijayan

“The Long Game: How the Chinese Negotiate with India” (2021) Vijay Gokhale

“Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and then Took on the West” (2021) Catherine Belton

“Russians: The People Behind the Power” (2014) Gregory Feifer

“The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin” (2016) Steven Lee Myers

“Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia” (2015) Peter Pomerantsev

“From Sheikhs to Sultanism: Statecraft and Authority in Saudi Arabia and the UAE” (2021) Christopher Davidson

“Assad or We Burn the Country: How One Family’s Lust for Power Destroyed Syria” (2020) Sam Dagher

“World War in Syria: Global Conflict on Middle Eastern Battlefields” (2021) A B Abrams

“The Spymaster of Baghdad: The Untold Story of the Elite Intelligence Cell that Turned the Tide against ISIS” (2021) Margaret Coker

“Blood and Oil: Mohammed bin Salman’s Ruthless Quest for Global Power” (2020) Bradley Hope & Justin Scheck

“Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World” (2021) Howard W French

“White Malice: The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa” (2021) Susan Williams

“King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa” (2019) Adam Hochschild and Barbara Kingsolver

“A Pretoria Boy” (2021) Peter Hain

“Ethiopia’s Transition and the Tigray Conflict” (2021) Lauren Ploch Blanchard

“Ethiopia and Eritrea: Insights into the Peace Nexus” (2020) Belete Belachew Yihun

“Searching for Boko Haram: A History of Violence in Central Africa” (2018) Scott MacEachern

“The Back Channel: American Diplomacy in a Disordered World” (2021) William Burns

“The Recruiter: Spying and the Lost Art of American Intelligence” (2021) Douglas London

“Midnight in Washington: How We Almost Lost Our Democracy and Still Could” (2021) Adam Schiff

“There Is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century” (2021) Fiona Hill

Beef, bible and bullets: Brazil in the age of Bolsonaro (2021) Richard Lapper

“Drug Wars and Covert Netherworlds: The Transformations of Mexico’s Narco Cartels” (2021) James Creechan

“Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS” (2016) Joby Warrick

“The Future of Terrorism: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and the Alt-Right” (Walter Laqueur)

“Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan” (2019) Steve Coll

“Behind Enemy Lies: War, News and Chaos in the Middle East” (2021) Patrick Cockburn

“The New Heretics: Understanding the Conspiracy Theories Polarizing the World” (2021) Andy Thomas

“War in 140 Characters” (2016) David Patrikarakos

“LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media” (2019) P. W. Singer

“The Age of AI: And Our Human Future” (2021) Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher

“This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends” (2021) Nicole Perlroth

“The Hacker and the State: Cyber Attacks and the New Normal of Geopolitics” (2020) Ben Buchanan

“Dawn of the Code War: America’s Battle Against Russia, China, and the Rising Global Cyber Threat” (2019) Garrett Graff and John Carlin

“How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need” (2021) Bill Gates

“The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations” (2021) Daniel Yergin

“Savage Ecology: War and Geopolitics at the End of the World” (2019) Jairus Victor Grove

“International Relations in the Anthropocene: New Agendas, New Agencies and New Approaches” (2021) David Chandler, Franziska Miller, and Delf Rothe (eds)

“Call Sign Chaos: Learning to Lead” (2021) Jim Mattis and Bing West

“Nine Lives: My Time As MI6’s Top Spy Inside al-Qaeda” (2018) Aimen Dean, Paul Cruickshank, and Tim Lister

“Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China” (2013) Ezra F Vogel

“The Power of Geography: Ten Maps That Reveal the Future of Our World” (2021) Tim Marshall

“Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed or Fail” (2021) Ray Dalio

“Terra Incognita: 100 Maps to Survive the Next 100 Years” (2020) Ian Goldin and Robert Muggah

“Geopolitics for the End Time: From the Pandemic to the Climate Crisis” (2021) Bruno Macaes

“The World in Conflict: Understanding the world’s troublespots” (2016) John Andrew

“Sea Power: The History and Geopolitics of the World’s Oceans” (2018) Admiral James Stavridis

“Goliath: Why the West Isn’t Winning. And What We Must Do About It” (2020) Sean McFate

“Border Wars: The conflicts of tomorrow” (2022) Klaus Dodds

“Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of Flags” (2017) Tim Marshall

“The Age of Walls: How Barriers Between Nations Are Changing Our World” (2019) Tim Marshall

“To Govern the Globe: World Orders and Catastrophic Change” (2021) Alfred McCoy

“A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide” (2013) Samantha Power

“The Armchair General: Can You Defeat the Nazis?” (2021) John Buckley

2021 has proven to be another exciting year for Encyclopedia Geopolitica, which celebrated its 5th birthday last month. We would like to take this opportunity to extend our thanks to our highly-involved readership, who have followed up each of our articles with excellent discussions on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Reddit. As the site’s editors, Simon Schofield and I would also like to extend a special thanks to our hardworking analyst team, without whom this would not be possible.

We suspect that 2022 will be an equally challenging year in the world of geopolitics, and we hope to be able to continue bringing you insightful and informative articles on those niche and under-examined geopolitical developments that we have tried to accurately capture this year.

As this list contains a large number of books, it may be worth considering Amazon’s Kindle “Unlimited” programme as a more cost-effective way to get through the reading list. Encyclopedia Geopolitica readers have access to a 30-day free trial for Kindle Unlimited, allowing them to sample over 1 million ebooks and thousands of audiobooks.

Encyclopedia Geopolitica is a collaborative effort to bring you thoughtful insights on world affairs. Our contributors include Military officers, Geopolitical Intelligence analysts, Corporate Security professionals, Government officials, Academics and Journalists from around the globe. Topics cover diplomatic and foreign affairs, military developments, international relations, terrorism, armed conflict, espionage and the broader elements of statecraft.

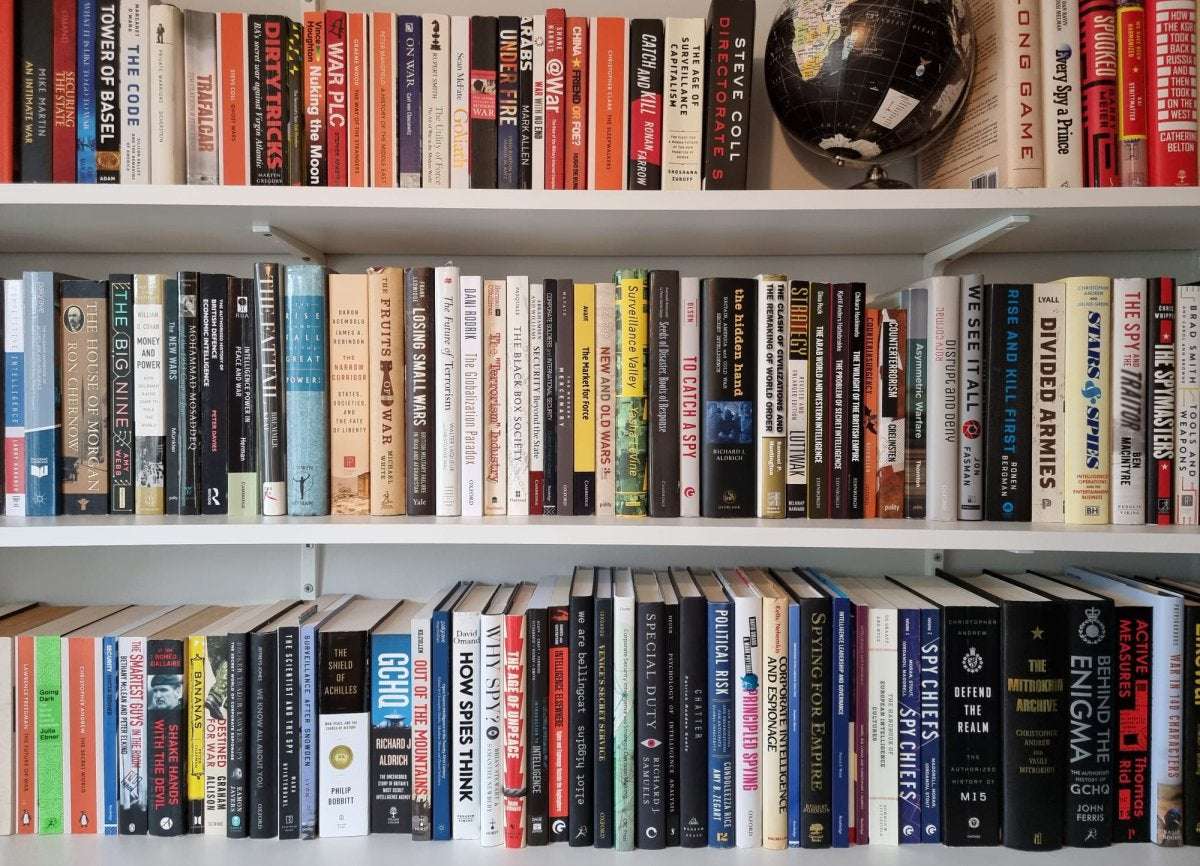

Picture credit: The Encyclopedia Geopolitica Editorial Library

Politicsbeerandguns on December 19th, 2021 at 15:32 UTC »

perfect timing, asked yesterday about it :)

fatboyhari on December 19th, 2021 at 15:31 UTC »

Thanks. Good list

sageandonion on December 19th, 2021 at 15:02 UTC »

Submission Statement: The 5th installment of the annual geopolitical reading list from Encyclopedia Geopolitica is now out. This year, we've decided to focus on a smaller selection of more highly focused recent releases, and a few slightly older books that we feel will be highly relevant for 2022. As always, the team and myself would like to extend our thanks to the members of this subreddit for the support and amazing discussions!

Happy New Year!

Lewis