Over the past decade, oil companies engaged in drilling and fracking have been allowed to pump in ground chemicals that, over time, can break down into toxins known as PFASs – a group of long-lasting compounds. group. Classes that are known to pose a threat. For people and wildlife — according to internal documents from the Environmental Protection Agency.

According to documents reviewed by The New York Times, in 2011 the EPA approved the use of these chemicals to reduce oil runoff from the ground, despite the agency’s own serious concerns about toxicity. was used for. The EPA’s approval of the three chemicals had not previously been publicly known.

Records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act by Physicians for Social Responsibility, a non-profit group, are among the first public indications that PFAS, the long-lasting compounds also known as “forever chemicals.” , may be present in the fluid used during drilling. . and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

In a consent order issued for the three chemicals on October 26, 2011, EPA scientists pointed to preliminary evidence that, under certain conditions, the chemical was PFOA, a type of PFAS chemical, and “may persist in the environment”. . and “can be toxic to people, wild mammals and birds.” EPA scientists recommended additional testing. Those tests were not mandatory and there is no indication that they were done.

“The EPA identified serious health risks associated with chemicals proposed for use in oil and gas extraction, and still allowed those chemicals to be used commercially,” said researcher Dusty Horwitt, from Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Documents dating from the Obama administration have been heavily amended because the EPA allows companies to enforce trade-secret claims to keep basic information on new chemicals from public release. The company name is also modified to those applying for approval, and records give only one generic name for the chemicals: Fluorinated Acrylic Alchemino Copolymer.

However, an identification number for one of the EPA-issued chemicals appears in separate EPA data and DuPont identifies the chemical as the first depositor. A separate EPA document shows that a chemical with the same EPA-issued number was first imported for commercial use in November 2011. (The chemicals did not exist until 2015, although its predecessor DuPont had responsibility for reporting the chemicals.)

There is no public data that details where EPA-approved chemicals have been used.

But the FrankFocus database, which tracks chemicals used in fracking, shows that about 120 companies used PFAS — or chemicals that can break down into PFAS; In more than 1,000 wells between 2012 and 2020 in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, New Mexico and Wyoming, the most common of which was “nonionic fluorosurfactant” and various misspellings. Because not all states require companies to report chemicals in the database, the number of wells may be higher.

Nine of those wells were in Carter County, Okla., within the boundaries of the Chickasaw Nation. “It’s not something I knew about,” said Chickasaw Nation spokesman Tony Choet.

EPA spokesman Nick Conger said the chemicals in question were approved a decade ago, and laws have since been amended to allow the agency to confirm the safety of new chemicals before they hit the market. He said the amendments to the documents were mandated by a statute protecting confidential business information. The Biden administration had made PFAS a top priority, he said, for example by proposing a rule from 2011 requiring all manufacturers and importers of PFAS to disclose more information on chemicals, including their environmental and health effects.

Chemours, which in the past has agreed to pay hundreds of millions of dollars to settle injury claims related to PFOA pollution, did not comment.

An Exxon spokesperson, in response to a question whether it uses chemicals, said, “We do not manufacture PFAS.”

Chevron did not respond to a request for comment.

The presence of PFAS in oil and gas extraction has affected oil field workers and emergency workers handling fires and spills, as well as people living near or beneath drilling sites, a class of chemicals known as its links. Known as, has faced increasing scrutiny. For cancer, birth defects and other serious health problems.

A class of man-made chemicals that are toxic even in very low concentrations, PFASs were used for decades to make products such as nonstick pans, stain-resistant carpets and fire extinguishing foams. Substances have been investigated in recent years for their tendency to persist in the environment and accumulate inside the human body, as well as their links to health problems such as cancer and birth defects. Both Congress and the Biden administration are better regulating PFAS, which contaminate the drinking water that nearly 80 million Americans consume.

Industry researchers have long known about their toxicity. But it wasn’t until the early 2000s, when environmental lawyer Rob Billotte founded Parkersburg, WA. In 2008, DuPont sued for contamination from its Teflon plant, that the dangers of PFAS became widely known. In agreement with the EPA in the mid-2000s, DuPont acknowledged knowing of the dangers of PFAS, and it and a handful of chemical manufacturers later committed to eliminating the use of certain types of PFAS by 2015. .

Shug, a professor of analytical chemistry at the University of Texas at Arlington, said the chemicals identified in the FrankFocus database fell into the PFAS group of compounds, although he said there was not enough information to draw a direct link between the two. Of the chemicals in the database, those approved by the EPA, he said it was clear that “the approved polymer, if and when it breaks down in the environment, will break down into PFAS.”

The findings underscore how, for decades, the country’s laws governing various chemicals have allowed thousands of substances to go into commercial use with relatively little testing. The EPA was assessed under the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976, which authorizes the agency to review and regulate new chemicals before they are manufactured or distributed.

But over the years, there were gaps in that law that left Americans exposed to harmful chemicals, experts say. In addition, the Toxic Substances Control Act has thousands of chemicals already in commercial use, including several PFAS chemicals. In 2016, Congress strengthened the law, strengthening the EPA’s authority to order health tests, among other measures. The Government Accountability Office, the watchdog arm of Congress, still identifies the Toxic Substance Control Act as a program. One of the highest risks of abuse and mismanagement.

In recent days, whistleblowers have accused The Intercept that the EPA’s office in charge of reviewing toxic chemicals tampered with assessments of dozens of chemicals to make them appear safe. EPA scientists evaluating new chemicals are “the last line of defense between harmful — even lethal — chemicals and their introduction into U.S. commerce, and this line of defense is struggling to maintain its integrity.” The whistle-blower said in its disclosure, which was issued by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, a Maryland-based non-profit group.

Brown, a public health toxicologist and former director of environmental epidemiology at the Connecticut Department of Health, said the EPA was “expressing concern at a level that should have caused alarm.” Of particular concern, he said, in oil and gas wells, “you’re putting the chemicals in a high-temperature, high-pressure environment and it’s highly reactive.”

EPA spokesman Mr. Kanger said the agency was committed to investigating whistleblower complaints.

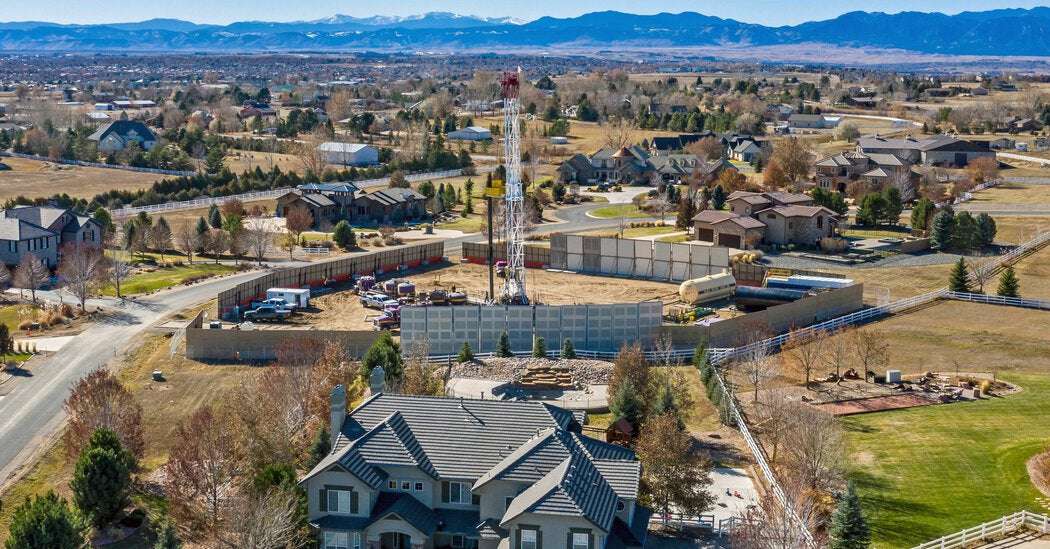

Concerns include the risks posed by hundreds of chemicals used in drilling and fracking, which include digging holes deep in the earth and then injecting millions of gallons of water, sand and chemicals into rock formations to unlock oil and gas deposits. . .

In a 2016 report, the EPA identified more than 1,600 chemicals used in drilling and fracking, or found in the fracking of wastewater, with close to 200 known to be carcinogens or toxic to human health. The same EPA report warned that fracking fluid could seep into groundwater from drill sites and could leak from underground wells that store millions of gallons of wastewater.

Communities near drilling sites have long complained of contaminated water and health problems, which they say are related. The lack of disclosure on what types of chemicals are present has hindered diagnosis or treatment. Various peer-reviewed studies have found evidence of a disproportionate burden on people living near oil and gas sites, people of color and other disadvantaged or marginalized communities, among other diseases and other health effects.

“In areas where there is heavy fracking, data is starting to build up to show a real cause for concern,” said Linda Birnbaum, former director of the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences and an expert on PFAS. He said the presence of PFAS is particularly worrying. “These are chemicals that will remain in the environment, essentially, not only for our lifetimes, but forever,” she said.

etr4807 on July 12nd, 2021 at 14:26 UTC »

I legitimately thought this was a known thing from years ago and was one of the biggest issues people had with fracking?

No-Lifeguard-8173 on July 12nd, 2021 at 13:21 UTC »

This domain only exists to plagiarize and rehost (with very minor changes and no attribution) legitimate author's content along with obtrusive advertisements that the thieves can profit from.

The original article is here. It's paragraph by paragraph the same with a few words changed.

bandit69 on July 12nd, 2021 at 13:10 UTC »

Just goes to show that no matter which side of the aisle the government sits on, corporations win over the citizens.

All the more reason there needs to be a major effort to convert to renewable fuels. Fossil fuels are getting harder and more expensive to extract, and causing major damage to the environment.