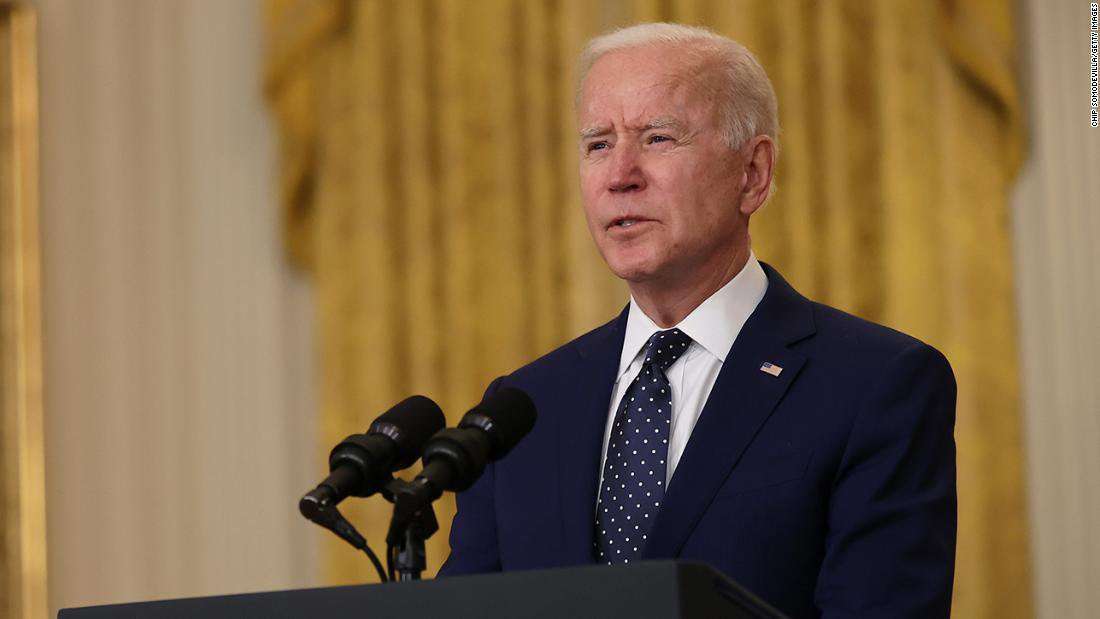

(CNN) President Joe Biden on Saturday became the first US president to officially recognize the massacre of Armenians under the Ottoman Empire as a genocide, risking a potential fracture with Turkey but signaling a commitment to global human rights.

In a statement marking the 106th anniversary of the massacre's start, Biden wrote, "Each year on this day, we remember the lives of all those who died in the Ottoman-era Armenian genocide and recommit ourselves to preventing such an atrocity from ever again occurring."

"Today, as we mourn what was lost, let us also turn our eyes to the future -- toward the world that we wish to build for our children. A world unstained by the daily evils of bigotry and intolerance, where human rights are respected, and where all people are able to pursue their lives in dignity and security," Biden said. "Let us renew our shared resolve to prevent future atrocities from occurring anywhere in the world. And let us pursue healing and reconciliation for all the people of the world."

The move fulfills Biden's campaign pledge to finally use the word genocide to describe the systematic killing and deportation of Armenians in what is now Turkey more than a century ago. Biden's predecessors in the White House had stopped short of using the word, wary of damaging ties with a key regional ally.

Earlier this week, US officials had been sending signals to allies outside the administration -- who have been pushing for an official declaration -- that the President would recognize the genocide. Addressing the potential move in an interview with a Turkish broadcaster this week, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said, "If the United States wants to worsen ties, the decision is theirs."

Cavusoglu on Saturday said Ankara completely rejects Biden's use of the term. "We are not going to take lessons about our history from anyone. Political opportunism is the biggest betrayal of peace and justice. We completely reject this statement that is only based on populism," he said in a tweet

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on Saturday offered condolences to "Ottoman Armenians, who lost their lives under the difficult circumstances of World War I." That message to Patriarch of Turkish Armenians Sahak Mashalian echoed Erdoğan's previous statements on April 24 and came before Biden's declaration.

Turkish Presidency communications director Fahrettin Altun later Saturday said that "the Biden administration's decision to misportray history out with an eye on domestic political calculations is a true misfortune for Turkey-U.S. relations."

Turkey later summoned David M. Satterfield , the US ambassador to the country, following the announcement, according to Turkish state media Anadolu.

"Turkey's strong reaction was conveyed to David Satterfield, who was accepted by Deputy Foreign Minister Sedat Onal, according to diplomatic sources," Anadolu reported. "Satterfield was told that Turkey finds the statement unacceptable, totally rejects and strongly condemns it."

The government of Turkey often registers complaints when foreign governments describe the event, which began in 1915, using the word "genocide." They maintain that it was wartime and there were losses on both sides, and they put the number of dead Armenians at 300,000.

Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump both avoided using the word genocide to avoid angering Ankara.

But Biden has determined that relations with Turkey and Erdoğan -- which have deteriorated over the past several years anyway -- should not prevent the use of a term that would validate the plight of Armenians more than a century ago and signal a commitment to human rights today.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan welcomed Biden's statement as such, tweeting that "the US has once again demonstrated its unwavering commitment to protecting human rights and universal values."

The declaration will not bring with it any new legal consequences for Turkey, only diplomatic fallout.

As vice president, Biden dealt frequently with Erdoğan and made four trips to Turkey, including in the aftermath of a failed coup attempt. But since then he's offered a less-than-rosy view of the Turkish leader.

"I've spent a lot of time with him. He is an autocrat," he told the New York Times editorial board in 2020. "He's the President of Turkey and a lot more. What I think we should be doing is taking a very different approach to him now, making it clear that we support opposition leadership."

Biden spoke by telephone with Erdoğan on Friday, his first conversation with the Turkish leader since taking office. The long period without communication had been interpreted as a sign Biden is placing less importance on the US relationship with Turkey going forward.

The two men agreed to meet in person on the sidelines of a mid-June NATO summit in Brussels. The White House said Biden conveyed "his interest in a constructive bilateral relationship with expanded areas of cooperation and effective management of disagreements," but the readout did not mention the Armenian genocide issue.

The campaign of atrocities Biden is acknowledging began the nights of April 23 and 24, 1915, when authorities in Constantinople, the Ottoman capital, rounded up about 250 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders. Many of them ended up deported or assassinated. April 24, known as Red Sunday, is commemorated as Genocide Remembrance Day by Armenians around the world.

The number of Armenians killed has been a major point of contention. Estimates range from 300,000 to 2 million deaths between 1914 and 1923, with not all of the victims in the Ottoman Empire. But most estimates -- including one of 800,000 between 1915 and 1918, made by Ottoman authorities themselves -- fall between 600,000 and 1.5 million.

Whether due to killings or forced deportation, the number of Armenians living in Turkey fell from 2 million in 1914 to under 400,000 by 1922.

While the death toll is in dispute, photographs from the era document some mass killings . Some show Ottoman soldiers posing with severed heads, others with them standing amid skulls in the dirt. The victims are reported to have died in mass burnings and by drowning, torture, gas, poison, disease and starvation. Children were reported to have been loaded into boats, taken out to sea and thrown overboard. Rape, too, was frequently reported.

As a candidate, Biden said that if he were elected, "I pledge to support a resolution recognizing the Armenian Genocide and will make universal human rights a top priority for my administration."

Similar pledges have gone unfulfilled before. When Obama was running for president, he declared in a lengthy statement that he shared "with Armenian Americans -- so many of whom are descended from genocide survivor -- a principled commitment to commemorating and ending genocide."

But like presidents before him, the realities of diplomacy intervened once he took office. In all eight years of his presidency, Obama avoided using "genocide" when commemorating the April event. With Turkey then positioned as a key partner in the fight against ISIS terrorists, the issue appeared even less palatable.

Some officials who served in Obama's administration, including his deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes and then-US Ambassador to the United Nations Samantha Power, later voiced regret at not having taken the step. Power is Biden's nominee to lead the US Agency for International Development.

In 2019, the House and Senate passed a resolution recognizing the mass killings of Armenians from 1915 to 1923 as genocide. Prior to its passage, the Trump administration had asked Republican senators to block the unanimous consent request several times on the grounds that it could undercut negotiations with Turkey.

Trump attempted to cultivate a friendship with Erdoğan, even as relations between Washington and Ankara soured over Turkey's purchase of a Russian-made air defense system and alleged human rights abuses by Turkish-backed forces in Syria.

A group of more than 100 Republican and Democratic lawmakers wrote a letter to Biden this month calling on him to formally recognize the Armenian genocide. The group was led by Rep. Adam Schiff, a California Democrat. A large Armenian American community resides in and around Schiff's district in Los Angeles.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said in a statement Saturday that "our hearts are full of joy that President Biden has taken the historic step of joining Congress with formal recognition on Armenian Genocide Day."

"To commemorate this solemn day of remembrance, let us pledge to always stand strong against hatred and violence wherever we see it and recommit to building a future of hope, peace and freedom for all the world's children."

This story has been updated with additional details Saturday.

silasgreenfront on April 24th, 2021 at 18:01 UTC »

Question for anyone who might know:

In practical terms, what is this likely to mean in terms of US-Turkey relations? I don't mean the usual rhetorical stuff - I mean trade, military concerns, that sort of thing.

The_Novelty-Account on April 24th, 2021 at 17:40 UTC »

So, there are questions in this thread and in others about why this genocide was recognized so late and why other similar genocides have yet to be recognized by the United States. As a lawyer working in international law, I wrote what I hope to be at least a partial answer. Unfortunately, the history is fairly complicated and generally poorly explained by news articles. TL;DR: The answer is two-fold, and explains why all countries are hesitant to declare certain actions genocide even within countries otherwise unimportant to their foreign policy. First, a declaration of genocide obliges the declarant to do anything and everything they are in a position to do to stop the genocide. Second, and most remarkable in the current case, the declaration forever helps define what the declaring country considers genocide.

In any case, and for the record, this declaration reflects the settled legal reality that this genocide absolutely and legally was a genocide.

First: The Erga Omnes Obligation

To understand the first prong, it is necessary to understand the legal concept of erga omnes. An erga omnes obligation is an obligation that all countries owe to each other and to the world, and is a label generally ascribed to the most important obligations (called jus cogens) which genocide is. It gives any country in the world standing in an international court when a violation of an erga omnes obligation occurs and another country does not stop it. It therefore gives all states the rights to invoke state responsibility for the other country’s failure to contain the genocide (very basically, state responsibility is similar to paying damages, see the ILC’s report on state responsibility, linked below). This means that states that do not perform their erga omnes obligation when it is their universal responsibility to do so open themselves up to claims internationally. Erga Omnes obligations were recognized by the International Court of Justice in Barcelona Traction at para 33:

The prevention of genocide as erga omnes was recognized by the International Law Commission of the United Nations through it’s Draft articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts, with commentaries at page 111 where it states:

The idea that genocide is an obligation erga omnes formally brought into law in the 1996 Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia PMO decision when the court, through an analysis of the purpose of the Genocide Convention found the prevention of genocide to be an obligation erga omnes. That said, in paragraph 31, it said something very interesting:

This was made even more explicit in the The Gambia v. Myanmar where the court said at para 41:

The parts that I have emphasized are a formal recognition that each state has an actual obligation to do something to prevent genocide in the case that an occurrence of e genocide exists, and as it is an erga omnes obligation, a state that recognizes a genocide, is in a position to help stop that genocide, but refuses to do so, has breached its erga omnes obligations and other states may invoke state responsibility over them for their failure to act. That is one of a few major reasons that states are hesitant to recognize genocides; they may be bound to act to stop that genocide if they so declare one.

Second: the Application of the Genocide Convention

One of the most important instruments in international law is the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. This treaty under Article 31(3)(b) on the general principles of interpretation states:

The Genocide Convention under Article II states:

The essence of these clauses is that the treatment of Genocide under the Genocide Convention compounds in on itself. While genocide is defined, there is not currently a list of actual specific actions undertaken by states that constitute genocide, which would be extremely helpful because according to the article you have to prove that the there was intent to destroy the group, which is based on actions and statements (there are many cases that speak to this requirement).

If the global community generally considers something to be genocide, then that thing that it considers genocide will gradually become indicative of the crime of genocide. Thus, countries risk creating legal situation where genocide becomes what they have declared it to be. While that sounds great, it also risks having the crime of genocide become meaningless as countries are willing to declare it whenever they suspect it, and thus gradually bring the net of behaviour that the genocide convention catches wider. The reason that this is a bad thing is that, as mentioned genocide’s erga omnes status is extremely serious and obliges states to act. A loose genocide definition actually makes the world less stable and makes states worse at preventing that genocide as genocide begins to mean less. Again, this comment is not meant to defend any country that shrinks away from its responsibilities.

In sum, international law makes the declaration of genocide a lot harder than base concerns about diplomacy (which absolutely still exist) and is actually much more complicated than people realize.

kokoyumyum on April 24th, 2021 at 17:21 UTC »

Finally. Overdue.