TEGs have been selected as the biomechanical energy harvesters in this wearable microgrid system due to their instant response to motions to generate energy. Since their inception in 2012, TEGs have become the most studied wearable mechanical energy harvesters due to its simple generation mechanism and the abundant selection of materials10,42. The present TEG module is composed of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-based negative mover and an ethylcellulose-polyurethane (EC-PU)-based positive stator in interdigitated patterns (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1), and is designed to harvest energy from sliding motions as illustrated in Fig. 2b43,44,45. To ensure the compatibility of the fabrication of the TEG elements to the e-textile platform with abundant flexibility and durability, each individual layer in the TEG was formulated into a screen-printable ink with elastomeric binder that is water-proof and resistant to abrasion. The TEG modules were characterized at low sliding frequencies ranging from 0.833 Hz to 3 Hz, simulating the realistic swinging speed of human arms from during walking (below 1 Hz) to running (1.5–3 Hz). As shown in Fig. 2c–d and Supplementary Fig. 6, the maximum peak voltage, independent from the frequency, was measured to be ca. 160 V. In contrast, the peak current grows nearly linearly with the frequency, from 45 μA at 0.833 Hz to 130 μA at 3 Hz, reflecting the linearly shortened time of transferring the same amount of charge between the mover and the stator46. To ensure that the TEG module is paired with commensurate storage rating, commercial electrolytic capacitors, with known capacitance ranging from 1 μF to 1 mF were used initially for the characterization, which were charged by a rectified TEG module in 60 s, 1.5 Hz sliding sessions while recording the capacitor voltage (Fig. 2e). To extrapolate the applicable performance data from the charging curves, the total harvested energy within the period and the harvested energy were calculated with the equation:

where E is the stored energy in the capacitor in J, C is a capacitance of the capacitor in F, and V is the voltage of the charged capacitor in V; and the average current was calculated with the equation:

where I is the average current from the TEG module in A, C is a capacitance of the capacitor in F, and \(\frac{{dV}}{{dt}}\) is the rate of voltage change in V s−1. Using the above equations, the total amount of stored energy and the average current was calculated and summarized in Fig. 2f. The average current remained mostly unchanged at 5.8 μA against different capacitors, while the energy stored maximized at 0.49 mJ near the load of 100 μF. The charging characteristics of the TEG modules at different frequencies were also tested and plotted in Fig. 2g–h. These data show a near-linear growth in stored energy and average current with the sliding frequency, which corroborated with the behavior observed in Fig. 2d. The mechanical durability of the TEG modules was also evaluated through repeated folding, crumpling and extended abrasion (Fig. 2i). The TEG modules were repeatedly folded with the radius below 1 mm for 100 cycles, and their open-circuit voltage (V OC ) during 1.5 Hz sliding motion was monitored, which has shown no discernible change (Fig. 2j). The TEG modules were also crumpled randomly and flattened repeatedly for 100 times, with their V OC when sliding monitored. The crumpling deformation had also shown no change in performance (Fig. 2k). The durability of the module against constant friction and washing was also tested, where the TEG module underwent constant sliding motion for over 2000 cycles and 20-min washing, where no visible drop in V OC was observed (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Fig. 21). The TEG modules could thus be considered a flexible and durable biomechanical energy harvest and were ready for integration. See Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Figs. 2–5 for the detailed device optimization, method of characterization, and performance calculation of the TEG.

Fig. 2: Characterization of the performance of the TEG module. a Schematic image of the layer-by-layer composition of the textile-based TEG module composed of a PTFE-based mover (top) and an EC-PU-based stator (bottom). b The charge generation mechanism of the TEG module under in-plane friction between the mover and the stator. The unrectified output peak voltages (c) and peak currents (d) of the TEG at different sliding frequencies. The charging of commercial capacitors with difference capacitance at 1.5 Hz in a 60-s period (e) and the corresponding stored energies and equivalent average DC currents (f). The charging of 100 μF capacitor at different frequencies in a 60-s period (g) and the corresponding stored energies and equivalent average DC currents (h). i Images of folded and crumpled TEG stator. Scale bar, 1 cm. The unrectified output peak voltages before and after 100 cycles of folding (j) and crumpling (k). l The long-term electrical signal from the TEG module under continuous sliding motions with the frequency of 1.5 Hz. Full size image

In the wearable microgrid system, BFCs offer the feature of harvesting biochemical energy continuously from metabolites present in biofluids via electroenzymatic reactions. Due to the high lactate concentrations in human sweat, a variety of sweat-based BFCs have been developed as wearable energy harvesters47,48,49,50,51. The wearable BFC modules were also screen-printed using various ink composites onto textile substrates. Carbon nanotubes (CNT)-based pellets were attached to interdigitated “island-bridge” interconnections (Fig. 3a-b and Supplementary Fig. 8) composed of flexible carbon composite as currents collectors and flexible silver composite as conductive interconnections. As illustrated in Fig. 3c, such bioenergy harvesting relies on the oxidation of lactate catalyzed by the lactate oxidase (LOx) immobilized on the bioanode, and on the oxygen reduction reaction facilitated by bilirubin oxidase (BOx) on the cathode. For efficient sweat bioenergy harvesting, the anode CNT pellets were preloaded with the 1,4-naphthoquinone (NQ) mediator while confining LOx with the glutaraldehyde (GA) cross-linker and chitosan; the CNT-based cathode pellets were decorated with protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) as the electron transfer promoter52, while immobilizing the BOx with Nafion. The detailed fabrication and composition of the anode and cathode pellets are described in the “Methods” section and Supplementary Notes 2. All in-vitro tests for characterization of the BFC were carried out in 0.5 M phosphate buffer solution (PBS) with pH of 7.4. Traditionally, wearable BFC devices are characterized with LSV, with scan rate near 5 mV s−1,11,16,49,52,53. However, for high-surface-area electrodes like the CNT pellets such high-speed LSV will result in an unrealistically high power due to the capacitive currents (Supplementary Fig. 11). Therefore, the fabricated BFC modules were characterized using chronoamperometry (CA) at different potentials in the presence of 15 mM lactate to reflect the realistic power output of the BFC in extended discharge sessions. The testing of the BFC modules resulted in a maximum power of 21.5 μW per module when discharging the BFC at 0.5 V (Fig. 3d–e). The response of the BFC to different lactate concentrations has been evaluated using CA, as shown in Fig. 3f, Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13, where the power per module increases from 9.7 μW at 5 mM lactate to 25.3 μW at 25 mM lactate. The mechanical durability and the stability of the BFC were also tested using CA. The module was bent 1000 times to 180° inward then outward with the radius of 1.3 cm (Fig. 3g), with the current at 0.5 V before and after bending in 10 mM lactate environment measured. As shown in Fig. 3h, the power of the BFC did not show any noticeable change before and after the bending. Such resiliency is attributed primarily to the “island-bridge” structure where the non-flexible, functional electrode pellets as the islands are connected by flexible, conductive silver interconnections. The stability of the BFC was tested also throughout the week (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 14). The BFC under test was stored in refrigerator under 4 °C and was taken out for testing every 24 h in a 10 mM lactate environment. The results of the individual CA measurements are summarized in Fig. 3i. Additional details of the fabrication and characterization of the BFC module, including its washability and stability in simulated sweat conditions, can be found in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figs. 7-11, 15, and 21.

Fig. 3: Characterization of the performance of the BFC module. a Schematic image of the textile-based BFC module composed of eight BOx-based cathodes and two LOx-based anodes connected by printed flexible interconnections. b A zoomed-in photo image of the fabricated BFC module. Scale bar, 5 mm. c The charge generation mechanism of the BFC from lactate and oxygen in sweats. d The output power of the BFC module at different discharge potentials with 15 mM lactate concentration. e The equivalent polarization curve derived from (d). f The output power of the BFC module discharged at 0.5 V under various lactate concentrations. g Image of the BFC module under 180° outward bending. Scale bar, 1 cm. h The power of the BFC module before and after the 1000 bending cycles. i The output power of the BFC module with 10 mM lactate concentration everyday within a week. Full size image

Flexible, printed SCs are selected for its ability to charge and discharge repeatedly and rapidly to deliver a flexible range of powers—a feature highly desirable for fast booting and pulsed high-power applications. A CNT and poly(3,4-ethylene dioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) hybrid capacitor, offering screen-printability and high flexibility, has been adopted as symmetrical interdigitated electrodes that are connected by flexible silver current collectors (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 15)54. Each SC module consists of 5 SC units connected in series to reach the desired 5 V voltage range for directly powering electronics, with each SC unit featuring four interdigitated CNT-PEDOT:PSS electrode segments covered by a solidified, transparent, flexible, sulfuric acid-crosslinked polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) electrolyte (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 16). The hybrid capacitor stores electric energy via both double-layer capacitance endowed by the high specific surface area CNTs and pseudocapacitance from the PEDOT:PSS, as illustrated in Fig. 4c. The areal capacitance of the printed SC material was characterized via both cyclic voltammetry (CV) at different scan rates and galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) with different currents. The GCD was conducted at charge/discharge between 0 V and 1 V with currents at 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 μA (Fig. 4d). The capacitance at discharge is used to gauge the capacitance of the SC unit, which is calculated using the equation:

$$C = \frac{{I\Delta t}}{{A( {E_f - E_i} )}}$$ (3)

where C is the areal capacitance in F cm−2, I is the current in A, Δt is the time taken for the discharge, A is the geometric area of electrodes, E f is the charged potential in V, and E i is the discharged potential in V. CV was carried out with the scan rates of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 mV s−1 between the window of 0 V and 1 V (Fig. 4e). The areal capacitance is calculated using the formula:

$$C = \frac{1}{{2{\it{\upnu }}{A}(E_f -E_i)}}\int_{{E}_i}^{{E}_f} {{I}\;{dV}}$$ (4)

where C is the areal capacitance in F cm−2, ν is the scan rate in V s−1, A is the geometric area of electrodes in cm2, E f is the higher vertex potential in V, E i is the lower vertex potential in V, and the I is the current in A. As agreed by both characterization methods, the capacitance of the printed SC was determined to be ca. 10 mF cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 17). Several SC modules can be connected in series or in parallel to adjust the overall capacitance to fit for harvesters and applications to obtain optimal charging speed and deliver sufficient energy (Fig. 4f). The stability of the module is analyzed by performing GCD cycles on the SC module. The mechanical stability of the module was evaluated by applying 1000 cycles of repeated inward-outward bending cycles at 180° with a bending radius of 0.5 cm (Fig. 4g). As shown in Fig. 4h, the charge-discharge behavior of the SC does not show any noticeable change before and after the 1000 cycles of bending deformation, suggesting the robust flexibility of the SC module for wearable applications. To prevent the leaching of the acidic electrolyte, the device is sealed by an additional layer of printed SEBS. The device can thus withstand extended wetting and washing without electrolyte leaching or observable degradation in its performance (Supplementary Fig. 21). The electrochemical stability of the SC module was studied by 1000 cycles of GCD between 0 V and 5 V with a current of 50 μA. As demonstrated in Fig. 4i, the areal capacitance of the SC shows a slight drop of areal capacitance after 1000 cycles to ca. 9 mF cm−2, while the coulombic efficiency gradually increases to 95%. The electrochemical performance of the SC is thus acceptable within the use-case of the microgrid, where roughly a few hundreds of charge-discharge cycles are expected. Detailed characterization and calculation of the SC performance are described in Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs. 18-19. Overall, each SC module was rated with the capacitance of ca. 150 μF.

Fig. 4: Characterization of the performance of the SC modules. a Schematic image of the textile-based SC energy storage module consisting of current collectors, CNT-PEDOT:PSS-based electrodes and PVA-based solid gel electrolyte. Each module is composed of five SC units connected in series. b The photo image of the printed SC module. Scale bar, 5 mm. c The charge storage mechanism of the hybrid SC unit based on both the double-layer capacitance and pseudocapacitance. d GCD with currents of 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 μA of a SC unit from 0 V to 1 V. e CV with scan rates of 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 mV s−1 from 0 V and 1 V of a SC unit. f GCD of the energy storage modules with different configurations, with (i) two storage modules in series; (ii) one storage module; and (iii) two storage modules in parallel. g Images of the inward and outward bending of the SC module. Scale bar, 1 cm. h 5 μA GCD of the SC module before and after 1000 cycles of 180º bending deformation. i The areal capacitance and coulombic efficiency of a SC unit in 1000 charge-discharge cycles. Full size image

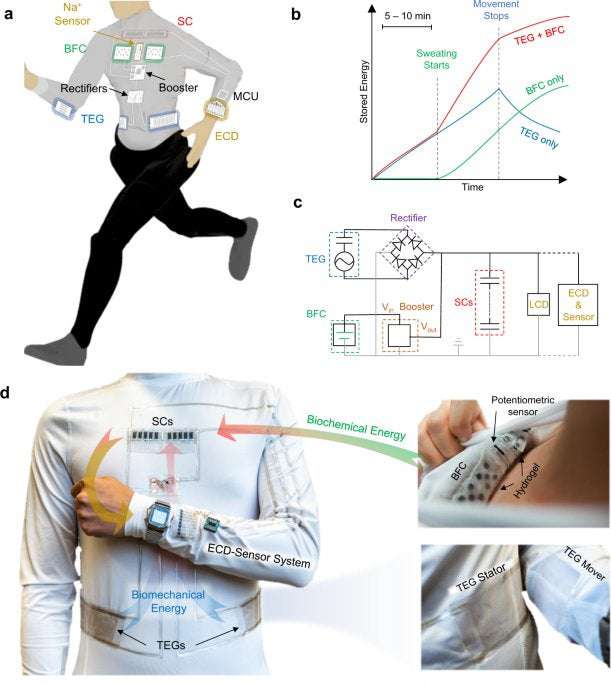

To demonstrate the synergistic effect of between TEG modules and BFC modules, a typical activity session has been simulated by applying constant 1 Hz–1.5 Hz sliding motions and spiking of 10–15 mM lactate fuel. Using this setting, three scenarios have been simulated: (i) movement starts followed by the start of perspiration; (ii) movements and perspiration taking place simultaneously; and (iii) movements stop but the perspiration continues. In the 4-min simulations, two TEG modules rectified by a bridge rectifier and one BFC module modulated by a DC voltage booster were used to charge one SC module (Supplementary Fig. 21). Each scenario was tested with only the TEG (blue curve), only the BFC (green curve), and both modules operating together (red curve). As shown in Fig. 5a, during the starting phase, the TEG module was able to charge the SC module immediately after starting the movement, whereas the BFC module was not able to provide power due to the lack of lactate. When lactate was spiked, the BFC started to respond to the fuel addition to provide power to the SC. The additive effect of integrating two complementary energy harvesters can be observed throughout the rest of the simulation, where their charging speed surpasses the individually operating harvesters. Such additive effect continued throughout the scenario (ii) and the first half of the scenario (iii). As soon as the sliding motion stopped, the TEG module stopped its operation instantaneously. In contrast, the BFC module continued to operate due to the presence of the lactate fuel to charge the SC module without interruption. Beyond the additive effects of two energy harvesters, the advantage of integrating the complementary TEG and BFC modules was demonstrated: at the start of the movement, the fast-booting TEG module can compensate for the slow-booting of the BFC; in return, the transiently harvesting TEG module was compensated by the extended-operating BFC module after the movement stops, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This synergistic behavior, not offered by any previous studies, is highly desirable for the reliable and sustainable operation of a self-powered wearable system. As expected, the charging speed of the 1 Hz sliding, 10 mM lactate simulation condition (Fig. 5a(i)-(iii)) was the slowest amongst all three, followed by the 1.5 Hz sliding, 10 mM lactate condition (Fig. 5a(iv)-(vi)), with the 1.5 Hz sliding, 15 mM lactate condition charging the capacitor fastest (Fig. 5a(vii)-(ix)). In all three situations, the synergistic additive effect was observed in all 3 phases of the condition, and the complementary fast-boosting and extended-harvesting effects were observed for the starting and ending phases of all 3 conditions, correspondingly.

Fig. 5: In-vitro and on-body charging performance of the wearable bioenergy microgrid system. a In-vitro charging curves of the individual and integrated harvester with (i)-(iii) 1 Hz frequency and 10 mM lactate; (iv)-(vi) 1.5 Hz frequency and 10 mM lactate; and (vii)-(ix) 1.5 Hz and 15 mM lactate for the TEG modules and the BFC modules, which simulate three representative phases: starting ((i), (iv), and (vii)), exercising((ii), (v), and (viii)) and ending((iii), (vi), and (ix)) of an activity session. b Photo illustration of the on-body testing arrangement. c On-body charging of a 150 μF SC using the individual BFC or TEG module alone, and with both modules combined, in a 10-min exercise session followed by a 20-min resting. d On-body charging of capacitors from SCs with (i) 75 μF, (ii) 150 μF, and (iii) 300 μF from 0 V in a 30-min exercise session to represent the charging of the system including the cold-starting phase of the voltage-booster. During the 30-min period, movement stops once the SC if fully charged to 5.1 V. Full size image

The synergistic effect of the integrated energy harvesting was further characterized with on-body tests to gauge the optimal capacitance that can mostly reflect such complementary fast-booting and extended-harvesting effects. Two TEGs, two BFCs and the corresponding SC modules were printed on the left and right sides of the waist, below the collar and in front of a shirt, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1c, and were connected via printed silver traces and enameled wires with proper insulations. A PVA-based PBS hydrogel was applied onto the BFC module for sweat capturing. A 10-min exercise session was carried out on a cycling machine, as illustrated in Fig. 5b, where the arm-swinging frequency was kept near 1.5 Hz, followed by 20 min of resting. Similar to the in-vitro simulation, the integrated on-body system was tested with only TEG, only BFC and with all harvesters operating together. Figure 5c demonstrates the on-body energy harvesting performance of the integrated system. For the system operating solely on TEG modules, the energy harvesting started immediately after the arm-swinging started and charged the SC module continuously throughout the 10-min exercise session. As soon as the movement stopped, the TEG stopped supplying power, and the SC module slowly self-discharged. For the system operated solely on the BFC module, the system suffered from slow booting with a 6-min delay. However, the BFC was able to supply power to the SC module quickly after sweating started, and fully charged the SC within 17 min Upon stopping the exercise, the BFC module was able to continuously supply power to the SC module over a 30-min period, reflecting the continuous presence of sweat. Lastly, the integrated system was able to compensate for both the slow booting and the transient harvesting, quickly fully charging the SC module in 7 min, maintaining maximum voltage over a 30-min period. In addition to the data presented in Fig. 5c, the on-body operation of the system was also tested with SC modules configurated with the capacitance of 75 μF, 150 μF, and 300 μF (Fig. 5d). The charging is started at 0 V instead of 2 V to demonstrate the booting of the voltage booster in the start of the operation. The SC modules were fully discharged to 0V and their potential monitored during charging, and the exercise sessions were only stopped when the SC is fully charged to 5.1 V or the limit of 30 min was reached. As shown in the figure, the time taken to fully charge the SC module increased as the capacitance increased for both the individual harvesters and the integrated microgrid harvesters. The synergistic and complementary behavior can still be observed in the booting phase of the charging, where the integrated harvesting system can fully charge the SC module faster than the individual harvesters, starting from the 4 min for 75 μF capacitor, to the 8 min for 150 μF capacitor and 12 min for the 300 μF capacitor. These results have thus validated the in-vitro simulation, fully illustrating the complementary and synergistic behaviors of the wearable microgrid system which offers fast-booting and extended-harvesting for energy harvesting in an activity session. Additional experimental details, data and discussion regarding the in-vitro and on-body tests can be found in Supplementary Note 4.

Two wearable applications were selected as examples of two operating modes for demonstrating the potential and advantages of the wearable microgrid system (Fig. 6a). The SC is an attractive energy storage module owing to its flexible discharge rates that allow powering of either low-power application continuously or of high-power application in a brief, pulsed fashion without damaging the module. For efficiently use the limited energy stored in the SC modules, the power consumption of the applications was characterized, and the SC modules were configured with minimum but sufficient capacitance for rapid booting while ensuring successful operation. Detailed fabrication and characterization procedures, additional data and further discussions can be found in Supplementary Notes 5 and Supplementary Figs. 22–31.

Fig. 6: Wearable bioenergy microgrid system with different applications. a Image of the LCD wristwatch and the ECD for the Na+ potentiometric sensor. Scale bar, 1 cm. b Images of the LCD screen with different input voltages. c The display of the ECD with different sensor voltage input. d The photo image of the all-printed flexible potentiometric sensor (top) and the calibration curve of the Na+ sensor (bottom). Scale bar, 2 mm. e-f Voltage vs. time curves of the wearable microgrid system powering the Na+ sensor-ECD system in pulsed mode during a 10-min running session followed by 20 min of rest, with only the BFC module operating, only the TEG module operating, and both harvesters operating together (e); and the LCD wristwatch continuously during a 7-min running session followed by 23 min of rest (f). Full size image

A textile-based sodium ion (Na+) sensor integrated with a wearable, flexible ECD pixeled display was developed as an example for applications with higher power demand operating in pulsed mode. The developed potentiometric Na+ sensor exhibited a near-Nernstian response to the concentration of the Na+ target, with a potential change of 57.19 mV per decade of concentration change (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 23). The sensor output can be instantly read by the pre-programmed integrated circuit and reported by changing the color of individually controlled ECD pixels, as illustrated in Fig. 6c and Supplementary Movie 2. The operation of the ECD pixels follows the simple reversible redox reaction of the PEDOT:PSS,

that takes place when a voltage above +1 V is applied to the back-panel electrodes, and the reduction reaction take place on the front panel and turn its color from light blue to dark blue (Supplementary Movie 1). A low-power microcontroller unit (MCU) was selected for reading the input from the Na+ sensor and controlling the on/off of the individual ECD pixels. The ECD is able to refresh rapidly and maintain the display without a continuous supply of power.

The set-up of the microcontroller is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 28. The controller was pre-programmed to display potential up to 0.32 V, with each ECD pixel corresponding to one 0.04 V increment of the sensor output. The power consumption of the microcontroller connected to the sensor-ECD system was measured similarly using the potentiostat set at different voltage, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 29. As shown, the power consumption of the microcontroller exceeded the wristwatch by 3 orders of magnitude, ranging from 4 mW at 2 V to 30 mW at 5 V. Yet, the microcontroller was able to boot quickly within the first 50 ms, take readings and apply signals to the ECD pixels within the first 200 ms, which allow this system to be powered transiently from the discharge of one charged capacitor. The energy consumed by one discharge session can be estimated by the equation:

where E is the energy in J, P is the power in W, and t is the time in s. To supply 200 ms of operation assuming the lowest power of ca. 4–5 mW, the energy required was thus estimated to be ca. 0.8–1 mJ. Capacitors ranging from 100 μF to 470 μF were able to supply sufficient energy to the microcontroller in one continuous discharge session with the larger capacitors had shown no substantial extended operation time (Supplementary Fig. 29b). The capacitors were discharged with 200 ms pulsed discharge, where more differences were more pronounced. The higher capacitance capacitors were able to sustain multiple refresh sessions, and the number of sessions decreases with the capacitance, as to 1 successful discharge session from the 100 μF with a slightly excess amount of energy, and 1 discharge from the 47 μF capacitor which did not last throughout the entire 200 ms session (Supplementary Fig. 29c). It is thus determined that the 75 μF SC modules should retain enough energy to sustain one complete refresh session. The required state of charge of the SC was then characterized by charging the 75 μF SC module to different potentials, and use the SC to power one refresh session, while the color on the ECD recorded to determine the minimum state of charge required for the 75 μF SC module to induce color change with sufficient contrast (Supplementary Fig. 30). It can be observed that the contrast of the on and off pixels gradually decreased with the initial state of charge of the SC modules, with the difference barely recognizable below 3.5 V. The minimum potential of 4 V before initiating a refresh session was thus decided. To confirm with the calculation above on the energy required for one operation session, the energy stored in the capacitor was calculated using equation:

where E SC is the energy discharged from the SC in J, C is the capacitance of the SC in F, V i 2 is the potential of the SC before the discharge in V, and V f 2 is the potential of the SC after the discharge in V. For a 75 μF SC to discharge from 4 V to 1.25 V, the energy released from the discharge is thus calculated to be 0.88 mJ, which agreed with the previous calculation based on Eq. (6). The 75 μF SC modules with a threshold voltage of 4 V was thus selected to allow fast booting while providing sufficient energy for a successful sense-refresh session.

The integrated wearable sensor-ECD application was integrated into the microgrid and tested on the body in a 10-min exercise session. As shown in Fig. 6e, the SC module was charged up to 4 V and discharged to refresh the sensor-ECD system. The fully integrated microgrid system was able to boot quickly within 3 min and intermittently refresh the results during the 30-min operation. In comparison, the BFC module suffered from slow booting due to delayed perspiration while the TEG modules were not able to sustain the operation after stopping the movement. It is worth noting that the faster boosting speed for the TEG-only scenario is due to the lack of need to supply a small amount of energy to boost the voltage booster. In both applications with different modes of operation, the wearable microgrid system—with its complementary and synergistic BFC-TEG harvesting and commensurate SC pairing—was able to deliver both fast-booting and extended-harvesting to ensure the autonomous and sustainable operation of the wearable platforms.

A low-power wristwatch with a LCD was chosen as a representative application that is continuously powered by the wearable microgrid system. The voltage of 2.5 V is determined as the turn-on threshold voltage, corresponding to the minimum voltage for the LCD to display with sufficient contrast (Fig. 6b). The power consumption of the watch was rated below 10 μW which has low requirement in storage unit (Supplementary Fig. 27). Two SC modules connected in-series with the capacity of 75 μF were selected to offer fast booting while maintaining extended operation when the microgrid harvests from human activities. Short, 8-min exercise sessions were carried out, with the potential of the SC recorded continuously. As illustrated in Fig. 6f, the simultaneous BFC-TEG energy harvesting was able to quickly boot the wristwatch within 2 min and maintain its continuous operation for over 30 min In contrast, the BFC-only system suffered from slow booting while the TEG-only system can only maintain the operation for a short time period before the SC module voltage dropped to below 2.5 V.

Finstermcbabyface on March 9th, 2021 at 13:46 UTC »

Kinda reminds me of the idea of stilsuits from dune

jctherik on March 9th, 2021 at 13:40 UTC »

I just want to point out that they're using microamps, microwatts and millivolts throughout that paper, so, if you just typed "exoskeleton" into the comments, your fingers used up more power pressing the buttons.

single_malt_jedi on March 9th, 2021 at 13:12 UTC »

Psh, scientists behind again. The Matrix made people in to power sources back in '99.