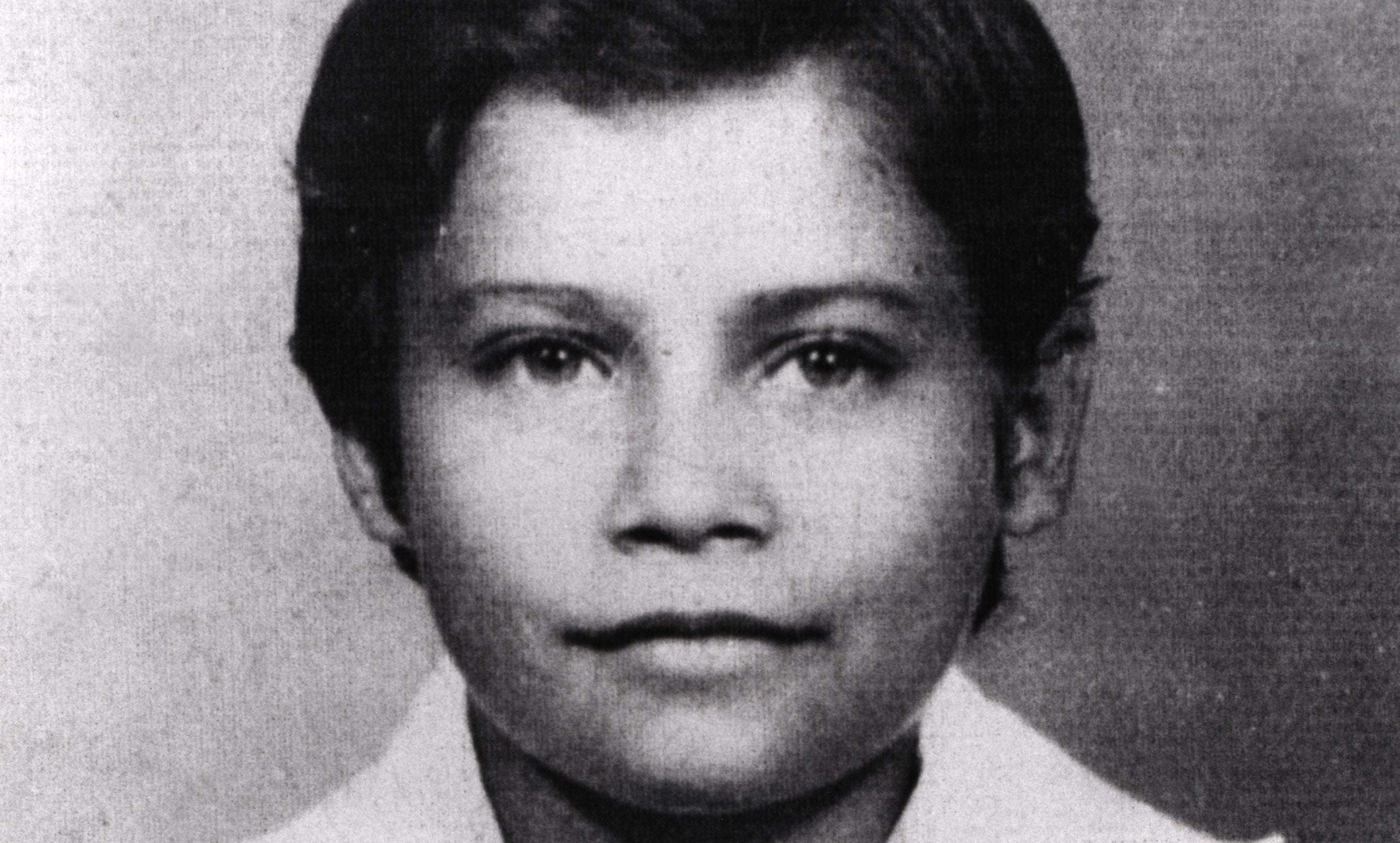

Nothing about Ramiro Cristales now immediately gives away that he’s spent most of his life eluding threats.

He seems comfortable in his own skin: a soft-spoken Canadian of Guatemalan heritage who also happens to have an inconceivable story of survival.

Since 1999, he’s lived under the radar in Canada. And throughout that time, he has refused to celebrate Christmas.

Ramiro Cristales spent his early years in Guatemala, but has been living under the radar in Canada for two decades. (Ousama Farag/CBC)

December is agonizingly enmeshed with the memory of losing his family, a memory that includes witnessing the killing of his little sister.

That particular episode was just one enduring image from a shocking coda to what had been an uncomplicated existence for Cristales and his six siblings in the village of Dos Erres, a hopeful settlement of farms nestled within lush jungle in the northern Peten department of Guatemala.

Cristales’s family grew corn, beans and rice, and raised pigs, cows and chickens. He was destined for some schooling but more likely a future in farming. He wasn’t old enough to ride horses yet, so the pigs had to do.

He had a twin brother, Eldo, and other brothers with names like Victor and Hector. His parents were Victor and Petrona.

Schoolchildren gather in Dos Erres for an Independence Day celebration on Sept. 15, 1982. (Submitted by Sara Romero)

At the time, Dos Erres was a relative oasis in a Guatemala that was a cauldron of chaos. But 1982 was an exceptionally brutal year in the civil conflict that had raged since 1960 between U.S.-backed government forces and leftist guerillas, supported by the Indigenous Maya. It was Mayan people who took the brunt of the violence. The rebellion followed a CIA decision to help remove a democratically elected president.

Earlier that year, General Efrain Rios Montt had taken power in a coup, and the military regime was bent on crushing the guerrilla fighters. Massacres and bodies were piling up.

Late in the year, fighters believed to belong to the guerrillas ambushed a convoy of soldiers not far from Dos Erres, killing several soldiers and seizing 22 rifles.

A few weeks later, in the early hours of Dec. 7, the war arrived at Dos Erres and turned out all the lights.

Armed soldiers dressed in civilian clothes came to try to find the fighters involved in the ambushes near Dos Erres, and to try to find the weapons they seized. They believed that, at best, the village harboured guerilla sympathizers.

The following version of what happened next is gleaned from court documents, testimony from participating soldiers, government archives, interviews with investigators in Guatemala and Cristales’s own recollections.

“It still feels like it was yesterday because it's something you never forget,” Cristales, now 41, said in an interview with The Fifth Estate.

The gunmen roused everyone from bed and marched them to the centre of town. Cristales remembers his mother and father tied with rope and marched out.

Cristales saw his father, Victor, left, and mother, Petrona, tied up and marched out of the centre of Dos Erros. (Submitted by Sara Romero)

His father said: “Everything will be OK,” recalled Cristales. But “it wasn't.”

It would be the last time he saw his father alive. Men were corralled in the school. Women and children were taken to the church.

What unfolded next was beyond the vilest imagination: the soldiers started by torturing the men and killing them, and then raping the women and killing them.

The worst of the violence unfolded by the village’s unfinished well.

Men, women and children, shot or bludgeoned to death, were dropped into the well. Some were thrown in still alive. At one point, at least one man threw in a grenade.

Dozens of others were killed elsewhere around the village. In the church where women and children were held, Cristales and his mother were within earshot as the carnage unfolded. His face and voice take on the character of a child as he recounts the traumatizing ordeal he lived that day. “The moment when they took my mom was the hardest part for me,” he said in an emotional interview.

He remembers clearly the face of the man taking his mother away — long, with a square jaw and narrow, wide-set eyes, high cheekbones and a mop of short, straight dark hair. It is a face he would see again.

In desperation, Cristales and his siblings tugged at their mother’s leg as the men dragged her out of the church, to no avail.

“They were like animals,” said Cristales.

He ran to the back of the church to peek through the wooden slats to see what was happening to his mother. At that point, he saw one of the men grab his little sister by the feet and swing her against a tree. He heard his mother pleading with them: “Please don’t kill my kids.”

Then came the moment when Cristales realized his mother was gone, too. “I was hearing my mom screaming for help, and then I hear no more.

Exhausted, Cristales fell asleep inside the church.

Hours later, when the killing was nearly over, he remembers thinking he was certain he would be next.

Instead, the soldiers took him out and asked whether he recognized any of the bodies strewn around the village.

“I don’t know this person,” Cristales recalls saying when the men pointed to one body.

“The person hanging from the tree was my dad.”

It was a demonstration of Cristales’s survival instinct kicking in, one that he would come to rely on to carry on for years to come.

A handful of kids had survived. One boy escaped, and at least two other girls, who were raped, were later killed, too. When it was all over, there were just two boys left: Ramiro, 5, and Oscar, only 3.

Both had green eyes and light skin but were unrelated. The men intended to take them alive, as a trophy or an act of mercy — it isn’t clear.

The killing spree over, the men marched them into the jungle, and together they walked for days.

Bizarrely, one of the men took a shine to Cristales and started feeding him. He remembered the long face: he was the man who took his mother away.

A few weeks later, that man would be taking him to his home.

roserouge on December 20th, 2020 at 06:41 UTC »

There is a This American Life podcast episode on this event. Even though I listened to it eight years ago, it still sticks in my head. For those interested, check out episode 465 (aired May 25, 2012). Title: What Happened at Dos Erres

ncsuandrew12 on December 20th, 2020 at 06:02 UTC »

That civil war was horrifying. My wife's family wouldn't let my brother-in-law leave the house growing up, for fear he would be grabbed and conscripted. I think he would've been about 10-12 when the war ended.

[edit] Also, in American Spanish classes they'll teach that "catch" translates to "coger". Not in Guatemala. There, it's a four-letter word that basically means rape f***. It was the word officers would use when instructing soldiers to grab girls.

[edit 2] He's fine. He's a mechanic and is teaching teenage boys how to be mechanics.

beardslap on December 20th, 2020 at 05:29 UTC »

He wasn’t ‘adopted’, he was abducted.