Dogs may never learn that every sound of a word matters

Despite their excellent auditory capacities, dogs do not attend to differences between words which differ only in one speech sound (e.g. dog vs dig), according to a new study by Hungarian researchers of the MTA-ELTE 'Lendület' Neuroethology of Communication Research Group at the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest measuring brain activity with non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG) on awake dogs. This might be a reason why the number of words dogs learn to recognize typically remains very low throughout their life. The study is published in Royal Society Open Science.

Dogs can distinguish human speech sounds (e.g. “d”, “o” and “g”) and there are similarities in the neuronal processing of words between dogs and humans. However, most of the dogs can learn a few words only throughout their lives even if they live in a human family and are surrounded by human speech. Magyari and her colleagues hypothesized that despite dog’s human-like auditory capacities for analyzing speech sounds, dogs might be less ready to attend to all differences between speech sounds when they listen to words.

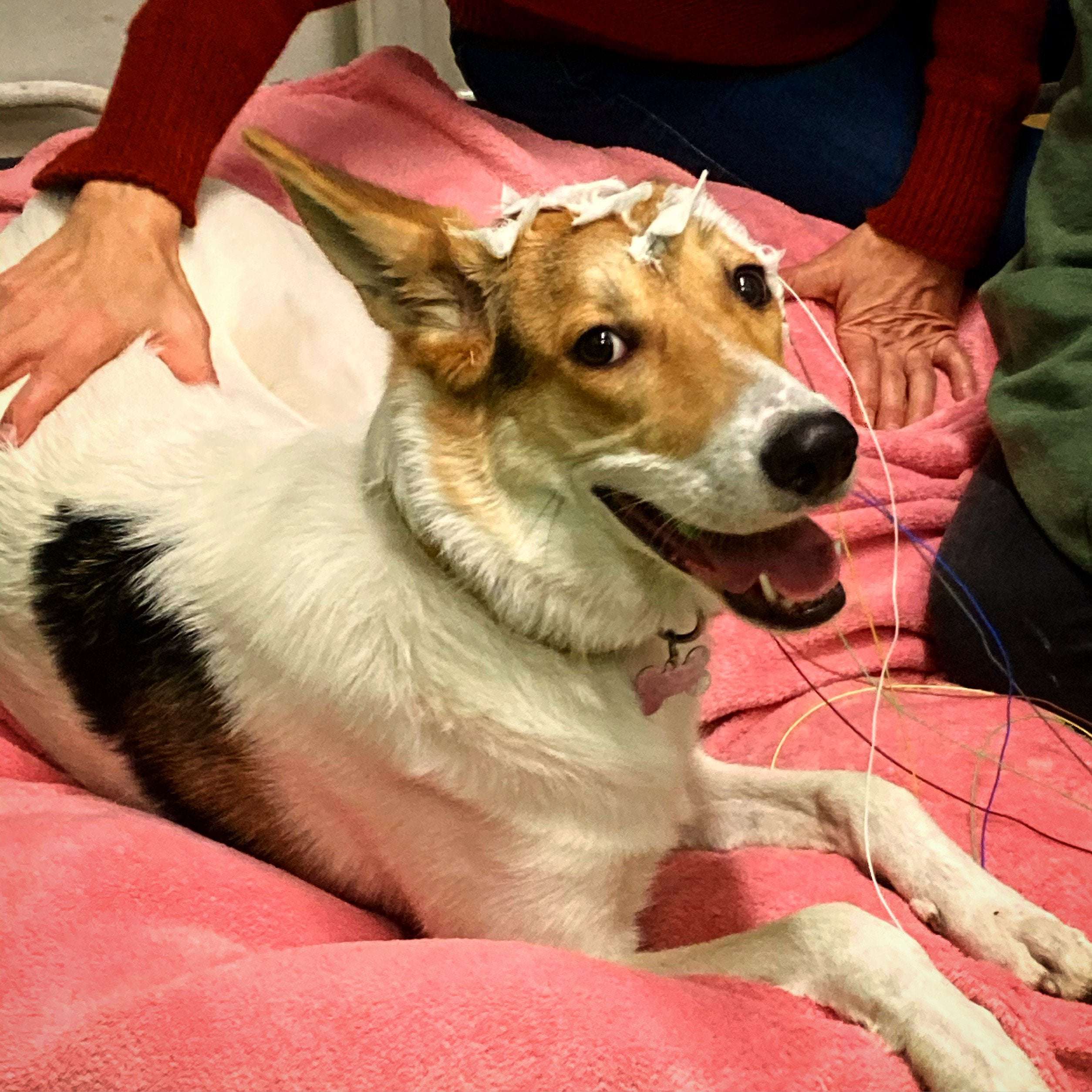

To test this idea, the researchers developed a procedure for measuring electrical activity in the brain non-invasively on awake, untrained, family dogs. Electroencephalography (EEG) is an often used technique in human clinical and research studies and it has been also successfully applied on tranquilized, sleeping or awake but trained dogs. However, in this study, the researchers measured EEG on awake dogs without any specific training.

Researchers invited dogs and their owners to the lab. After the dog got familiar with the room and the experimenters, the experimenters asked the owner to sit down on a mattress together with her dog as it would be a relaxation time for them. Then, the experimenters put electrodes on the dog’s head and fixed it with a tape. With the electrodes on, dogs listened to tape-recorded instruction words they knew (e.g. “sit”), to similar but nonsense words (e.g. “sut”), and to very different nonsense words (e.g. “bep”).

“The electroencephalography is a sensitive method not only to brain activity but also to muscle-movements. Therefore, we had to make sure that dogs tense their muscles as little as possible during measurement. We also wanted to include any type of family dogs in our study not only specially trained animals. Therefore, we decided that instead of training our dog-participants, we will ask them just to relax. Of course, some of the dogs who came to the experiment could not settle down and did not let us do the measurement. But the dropout rate from the study was similar to the dropout rate in EEG studies with human infants. It was also an exciting process for us to learn how we can create a relaxing and safe atmosphere in the lab for both the dogs and their owners.” -says lead author Lilla Magyari, postdoctoral researcher at Department of Ethology, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary.

The analysis of the recorded electric brain activity showed that dog brains clearly and quickly discriminated the known words from the very different nonsense words starting from 200 ms after the beginning of the words. This effect is in line with similar studies on humans which show that the human brain responds differently to meaningful and nonsense words already within a few hundred milliseconds. But the dogs’ brains made no difference between known words and those nonsense words that differed in a single speech sound only. This pattern is more similar to the results of experiments with human infants who are around 14-months. Infants become efficient in processing phonetic details of words, which is an important prerequisite for developing a large vocabulary, between 14 and 20 months. But younger infants do not process phonetic details of words in certain experimental and word learning situations despite the fact that infants are able to differentiate speech sounds perceptually within weeks after birth.

“Similarly to the case of human infants, we speculate that the similarity of dogs’ brain activity for instruction words they know and for similar nonsense words reflects not perceptual constraints but attentional and processing biases. Dogs might not attend to all details of speech sound when they listen to words. Further research could reveal whether this could be a reason that incapacitates dogs from acquiring a sizable vocabulary.”- concludes Attila Andics, principal investigator of the MTA-ELTE 'Lendület' Neuroethology of Communication Research Group.

This study was published on the 9th of December in Royal Society Open Science titled “Event-related potentials reveal limited readiness to access phonetic details during word processing in dogs”, written by Lilla Magyari, Zsófia Huszár, Andrea Turzó and Attila Andics. This research was funded by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Lendület Program), the National Research, Development and Innovation Office and the Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

OneTreePhil on December 9th, 2020 at 13:39 UTC »

Do dogs understand some languages better than others? Could we design a language that's very easy for dogs to understand? Pupsperanto?

spap-oop on December 9th, 2020 at 12:48 UTC »

A friend of mine when I was a kid had a little poodle.

They’d call “CheeeeeeeeeeeroKE!” With the first two syllables at a high note and dropping on the third, and the dog would come running.

My friend and I would call other things, like

“VaaaaaaaaaacumCLEANER”

and the little dog would come running.

mvea on December 9th, 2020 at 11:59 UTC »

The post title is from the linked academic press release here:

Dogs may never learn that every sound of a word matters

Despite their excellent auditory capacities, dogs do not attend to differences between words which differ only in one speech sound (e.g. dog vs dig), according to a new study by Hungarian researchers of the MTA-ELTE 'Lendület' Neuroethology of Communication Research Group at the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest measuring brain activity with non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG) on awake dogs. This might be a reason why the number of words dogs learn to recognize typically remains very low throughout their life.

The source journal article is here:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.200851

Event-related potentials reveal limited readiness to access phonetic details during word processing in dogs

L. Magyari , Zs. Huszár , A. Turzó and A. Andics

Royal Society Open Science

Published:09 December 2020

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200851

Abstract

While dogs have remarkable abilities for social cognition and communication, the number of words they learn to recognize typically remains very low. The reason for this limited capacity is still unclear. We hypothesized that despite their human-like auditory abilities for analysing speech sounds, their word processing capacities might be less ready to access phonetic details. To test this, we developed procedures for non-invasive measurement of event-related potentials (ERPs) for language stimuli in awake dogs (n = 17). Dogs listened to familiar instruction words and phonetically similar and dissimilar nonsense words. We compared two different artefact cleaning procedures on the same data; they led to similar results. An early (200–300 ms; only after one of the cleaning procedures) and a late (650–800 ms; after both cleaning procedures) difference was present in the ERPs for known versus phonetically dissimilar nonsense words. There were no differences between the ERPs for known versus phonetically similar nonsense words. ERPs of dogs who heard the instructions more often also showed larger differences between instructions and dissimilar nonsense words. The study revealed not only dogs' sensitivity to known words, but also their limited capacity to access phonetic details. Future work should confirm the reported ERP correlates of word processing abilities in dogs.