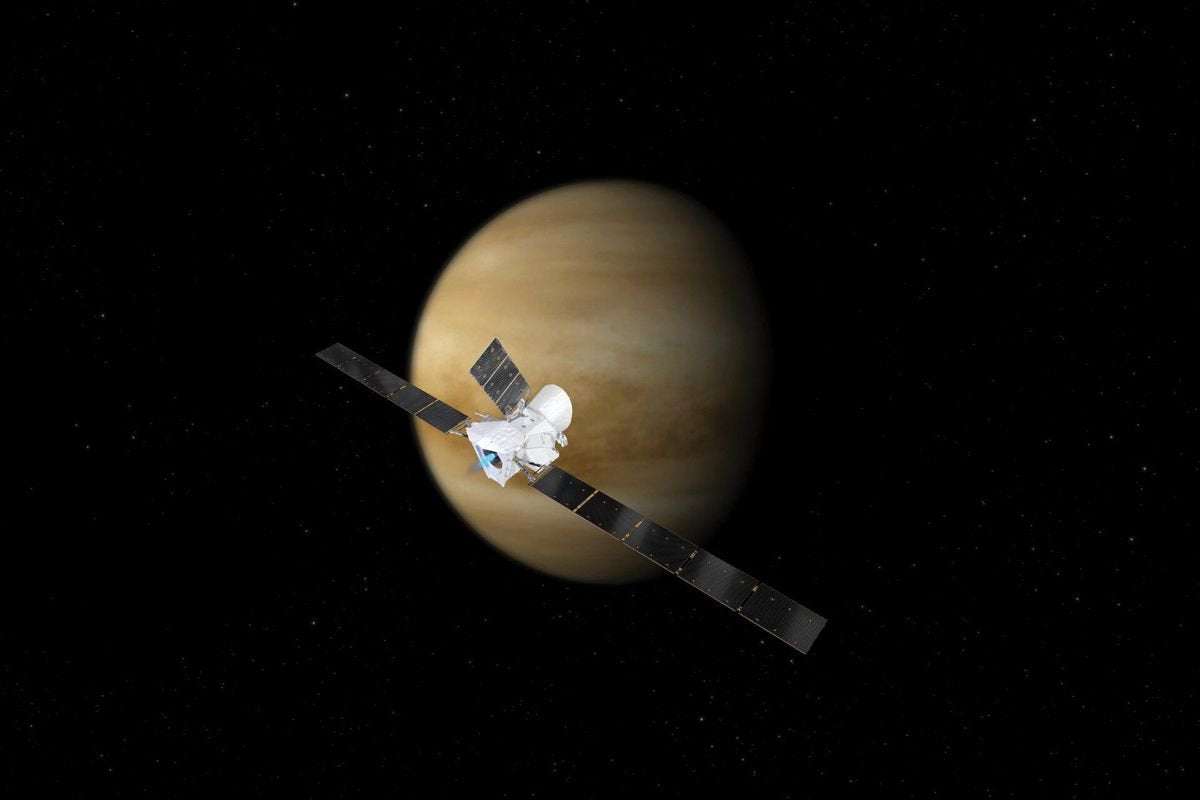

BepiColombo is just weeks away from its first of two Venus flybys. ESA/ATG medialab

Earlier this week, scientists announced the discovery of phosphine on Venus, a potential signature of life. Now, in an amazing coincidence, a European and Japanese spacecraft is about to fly past the planet – and could confirm the discovery.

On Monday, September 14, a team of scientists said they had found evidence for phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus. The region in which it was found, about 50 kilometers above the surface, is outside the harsh conditions on the Venusian surface, and could be a habitat for airborne microbes.

To find out for sure, we will need to send a mission into the Venusian atmosphere to look for such life. Several proposals are on the table, with the closest being a spacecraft from the U.S. company Rocket Lab that could send a probe into the atmosphere as soon as 2023.

As far as we know, the phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus could have been produced by life, although it's possible it could also be produced by an unknown non-biological process. Before missions start launching to Venus to find out, however, scientists will want to know for sure if phosphine is really present.

And as luck would have it, a joint mission comprising two spacecraft – one from the European Space Agency (ESA) and the other from the Japanese space agency (JAXA) – is about to fly past Venus that could tell us for sure.

BepiColombo, launched in 2018, is on its way to enter orbit around Mercury, the innermost planet of the Solar System. But to achieve that it plans to use two flybys of Venus to slow itself down, one on October 15, 2020, and another on August 10, 2021.

BepiColombo launched on October 19, 2018. AFP via Getty Images

The teams running the spacecraft already had plans to observe Venus during the flyby. But now, based on this detection of phosphine from telescopes on Earth, they are now planning to use both of these flybys to look for phosphine using an instrument on the spacecraft.

“We possibly could detect phosphine,” says ESA's Johannes Benkhoff, BepiColombo's Project Scientist. “But we do not know if our instrument is sensitive enough.”

The instrument on the European side of the mission, called MERTIS (MErcury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer), is designed to study the composition of the surface of Mercury. However, the team believe they can also use it to study the atmospheric composition of Venus during both flybys.

On this first flyby, the spacecraft will get no closer than 10,000 kilometers from Venus. That’s very far, but potentially still close enough to make a detection.

“There actually is something in the spectral range of MERTIS,” says Jörn Helbert from the German Aerospace Center, co-lead on the MERTIS instrument. “So we are now seeing if our sensitivity is good enough to do observations.”

Phosphine could be a biosignature of life in the Venusian atmosphere. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Peter Rubin

As this first flyby is only weeks away, however, the observation campaign of the spacecraft is already set in stone, making the chance of a discovery slim. More promising is the second flyby next year, which will not only give the team more time to prepare, but also approach just 550 kilometers from Venus.

“[On the first flyby] we have to get very, very lucky,” says Helbert . “On the second one, we only have to get very lucky. But it’s really at the limit of what we can do.”

If a detection can be made, it would provide independent verification of the presence of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus. And for future missions planning to visit the planet, which alongside Rocket Lab’s mission includes potential spacecraft from NASA, India, Russia, and Europe, that could be vital information.

Even if the first flyby is unsuccessful in detecting phosphine, the team plan to use lessons learned to revise their observations for the second flyby. And it just might be that this mission, in a happy coincedence, could contribute to a major scientific discovery before it even reaches its intended target.

“It’s kind of perfect timing,” says Helbert . “Now [the flyby] is even more exciting.”

AliB3 on September 16th, 2020 at 21:13 UTC »

If this is the year we discover aliens I'm going to freak the fuck out.

Radioiron on September 16th, 2020 at 18:57 UTC »

If the spacecraft suddenly stops and is completely disassembled we're going to be in some deep shit.

Minnesodomy55126 on September 16th, 2020 at 18:56 UTC »

Wow. We are actually really lucky to be getting a flyby right now. Otherwise we would have had to wait several more years. Maybe just one.