Loving v. Virginia was a Supreme Court case that struck down state laws banning interracial marriage in the United States. The plaintiffs in the case were Richard and Mildred Loving, a white man and black woman whose marriage was deemed illegal according to Virginia state law. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Lovings appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously that so-called “anti-miscegenation” statutes were unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. The decision is often cited as a watershed moment in the dismantling of “Jim Crow” race laws.

The Loving case was a challenge to centuries of American laws banning miscegenation, i.e., any marriage or interbreeding among different races. Restrictions on miscegenation existed as early as the colonial era, and of the 50 U.S. states, all but nine had a law against the practice at some point in their history.

Early attempts to dispute race-based marriage bans in court met with little success. One of the first and most noteworthy cases was 1883’s Pace v. Alabama, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that an Alabama anti-miscegenation law was constitutional because it punished blacks and whites equally. In 1888, meanwhile, the high court ruled that states had the authority to regulate marriage.

By the 1950s, more than half the states in the Union—including every state in the South—still had laws restricting marriage by racial classifications. In Virginia, interracial marriage was illegal under 1924’s Act to Preserve Racial Integrity. Those who violated the law risked anywhere from one to five years in a state penitentiary.

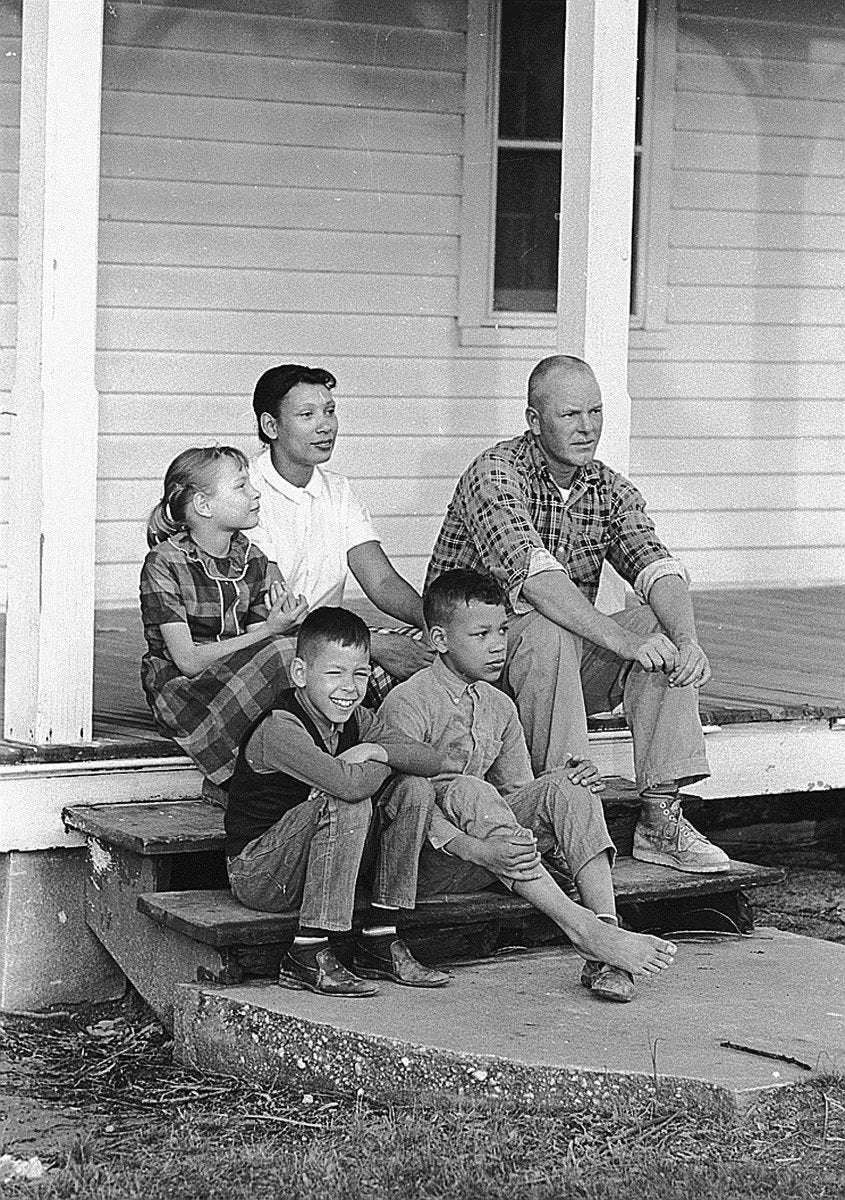

The central figures in Loving v. Virginia were Richard Loving and Mildred Jeter, a couple from the town of Central Point in Caroline County, Virginia.

Richard, a white construction worker, and Mildred, a woman of mixed African American and Native American ancestry, were longtime friends who had fallen in love. In June 1958, they exchanged wedding vows in Washington, D.C., where interracial marriage was legal, and then returned home to Virginia.

On July 11, 1958, just five weeks after their wedding, the Lovings were woken in their bed at about 2:00 a.m. and arrested by the local sheriff. Richard and Mildred were indicted on charges of violating Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law, which deemed interracial marriages a felony.

When the couple pleaded guilty the following year, Judge Leon M. Bazile sentenced them to one year in prison, but suspended the sentence on the condition that they would leave Virginia and not return together for a period of 25 years.

Following their court case, the Lovings were forced to leave Virginia and relocate to Washington, D.C. The couple lived in exile in the nation’s capital for several years and raised three children—sons Sidney and Donald and a daughter, Peggy—but they longed to return to their hometown.

In 1963, a desperate Mildred Loving wrote a letter to U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy asking for assistance. Kennedy referred the Lovings to the American Civil Liberties Union, which agreed to take their case.

The Loving V. Virginia Supreme Court Case

The Lovings began their legal battle in November 1963. With the aid of Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop, two young ACLU lawyers, the couple filed a motion asking for Judge Bazile to vacate their conviction and set aside their sentences.

When Bazile refused, Cohen and Hirschkop took the case to the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, which also upheld the original ruling. Following another appeal, the case made its way to the United States Supreme Court in April 1967.

During oral arguments before the Supreme Court, Virginia’s Assistant Attorney General Robert D. McIlwaine III defended the constitutionality of his state’s anti-miscegenation law and compared it to similar regulations against incest and polygamy. Cohen and Hirschkop, meanwhile, argued the Virginia statute was illegal under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees all citizens due process and equal protection under the law.

During one exchange, Hirschkop stated that Virginia’s interracial marriage law and others like it were rooted in racism and white supremacy. “These are not health and welfare laws,” he argued. “These are slavery laws, pure and simple.”

The Supreme Court announced its ruling in Loving v. Virginia on June 12, 1967. In a unanimous decision, the justices found that Virginia’s interracial marriage law violated the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

“Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the state,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote.

The landmark ruling not only overturned the Lovings’ 1958 criminal conviction, it also struck down laws against interracial marriage in 16 U.S. states including Virginia.

The Lovings had lived secretly on a Virginia farm for much of their legal battle, but after the Supreme Court decision, they returned to the town of Central Point to raise their three children.

Richard Loving was killed in 1975 when a drunk driver in Caroline County struck the couple’s car. Mildred survived the crash and went on to spend the rest of her life in Central Point. She died in 2008, having never remarried.

Loving v. Virginia is considered one of the most significant legal decisions of the civil rights era. By declaring Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional, the Supreme Court ended prohibitions on interracial marriage and dealt a major blow to segregation.

Despite the court’s decision, however, some states were slow to alter their laws. The last state to officially accept the ruling was Alabama, which only removed an anti-miscegenation statute from its state constitution in 2000.

In addition to its implications for interracial marriage, Loving v. Virginia was also invoked in subsequent court cases concerning same-sex marriage.

In 2015, for example, Justice Anthony Kennedy cited the Loving case in his opinion on the Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized gay marriage across the United States.

June 12—the anniversary of the Loving v. Virginia decision—is now commemorated each year as “Loving Day,” a holiday celebrating multiracial families.

Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law—an American History. By Peter Wallenstein.

Loving v. Virginia. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute.

Law and the Politics of Marriage: Loving v. Virginia After 30 Years Introduction. Robert A. Destro.

What You Didn’t Know About Loving v. Virginia. Time Magazine.

elfratar on June 13rd, 2020 at 00:05 UTC »

In June 2007, Mildred Loving issued the following statement:

sephstorm on June 12nd, 2020 at 22:36 UTC »

Only 53 years ago.

Well just a reminder of how people always resist change. Many times its worth it.

srvmshr on June 12nd, 2020 at 21:38 UTC »

The surname could not have been more symbolic. Good landmark judgement!