Genes Have Their Moment Before the Supreme Court

July 2013—Knowledge is power, so people can get pretty testy when kept in the dark—especially when it’s about their own genes, and especially when those genes could increase the risk of a disease as high-profile as breast cancer. Maybe Myriad Genetics should have thought about that before choosing to monopolize the tests for BRCA1 and BRCA2, two genes that are responsible for 5-10 percent of all breast cancers and more than 50 percent of hereditary breast cancers.

In 1990, Mary-Claire King, a geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley, linked a gene in a small region of chromosome 17 to hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. Four years later, Myriad Genetics won the race to isolate the gene, dubbed BRCA1, and sequence it. BRCA2, similar to BRCA1 but located on a different chromosome, was isolated by a British lab in 1995 and sequenced by Myriad in 1996.

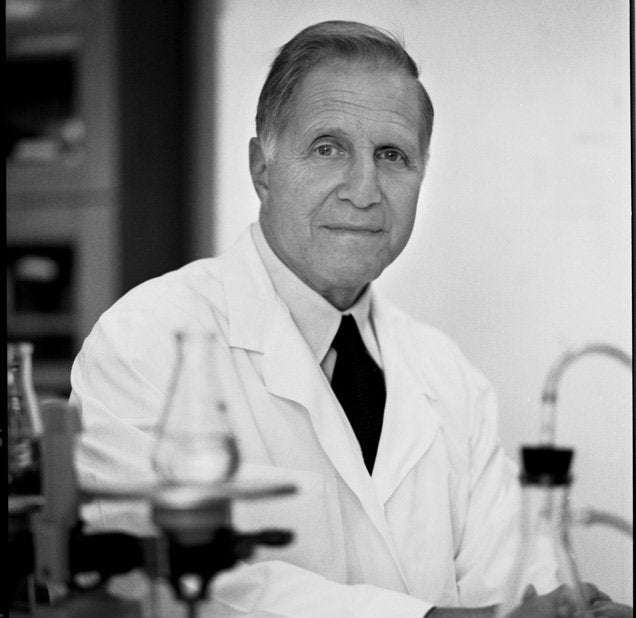

Around the same time, Haig Kazazian, M.D., then the chair of the Department of Genetics at the University of Pennsylvania, recruited Arupa Ganguly, Ph.D., to join the faculty because of her skill in developing a genetic testing technique tailored to large genes like the BRCAs.

According to Kazazian, now a professor of human genetics at the Johns Hopkins University’s McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Ganguly’s lab at Penn started offering BRCA tests to patients in late 1995. Three years later, they had tested about 1,000 women with family histories of breast cancer, and nearly 300 were positive for a defect in one of the genes. Then, in 1998, Kazazian got a dinner invitation that included Mark Skolnick, a founder of Myriad Genetics. “He told me after dinner that Myriad would be sending us a ‘cease and desist’ letter since they had successfully patented both BRCA genes earlier that year,” says Kazazian. Upset by the news for many reasons, the only silver lining Kazazian could find was that Skolnick had paid for their dinner.

Biomedical patents necessarily create conflicts between stakeholders in ways that patents on most other things do not. Patents incentivize inventors’ investment of time and money with the promise of a temporary monopoly that will allow the inventor to make a profit from their invention before competitive market forces come into play and force the price down. When the newly patented item is a new gadget, these monopolies and higher prices are, in general, easily tolerated.

But with biomedical patents, the potential consumers are generally patients whose needs are urgent and life-altering. Our society might not tolerate most biomedical patents at all if it weren’t for the ability of health insurance companies to buffer most consumer-patients from the brunt of temporarily inflated prices.

Patents on gene sequences have been allowed by the U.S. Patent Office since 1980. Back then, determining the sequence of a gene was no easy task, and patents incentivized companies and universities to search the genome for disease-causing mutations that could be used to diagnose any number of genetic diseases.

In fact, Kazazian, together with Garry Cutting, M.D., a professor of pediatrics here at the school of medicine, and Stylianos Antonarakis, M.D., D.Sc., now chair of Genetic Medicine at the University of Geneva, held a patent on four mutations that are found in the CFTR gene, which is responsible for causing cystic fibrosis. Kazazian says there are two major differences between that patent and Myriad’s. First, that patent (which expired more than a year ago) was for specific mutation sequences within the CFTR gene, not for the whole gene. The fact that Myriad holds a patent on all of BRCA1 and 2 means that any mutations ever identified in them would also “belong” to the company a priori. The second difference is in the way Myriad refused to license the test to other diagnostic centers, so that it remained the sole legal provider of the test. In contrast, Kazazian and his colleagues licensed the test to at least 15 different companies and received royalties in return.

Gene patents come in two basic flavors: gene applications and gene tests. Patents on gene applications are quite similar to those on drugs. Many drugs exist in nature and aren’t exactly “invented,” but rather discovered, purified and put to use. Patented gene applications include cDNA therapies, which decrease the protein output of a disease-causing gene, and genetically modified organisms, whose genomes are altered by researchers to include a gene sequence that benefits the organism (e.g., bug-resistant corn) or us (e.g., bacteria that produce insulin for diabetics).

Gene-testing patents are quite different from drug patents because they are diagnostic, not therapeutic. This difference has several downstream effects. First of all, not all insurance companies cover genetic diagnostic tests for people who are not even sick (yet). In the case of BRCA testing, women generally request the test because of a family history of breast cancer, rather than a detectable, physiological change. A woman who is insured by the Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan for federal employees, for example, will only be reimbursed for BRCA testing if she has already been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer. So, in general, consumers of these gene tests (that is, potential patients) are more likely to feel the full force of patent-protected high pricing than they would for other patented biomedical products.

Secondly, a monopoly on a diagnostic test arguably makes that test less reliable because doctors cannot have its results checked by an alternative method or even by another lab or company.

In 1998, a woman with a family history of breast cancer who wanted to be tested for BRCA could be tested at Penn and/or Myriad, and there were a few other labs developing tests for research purposes, too. The test Ganguly developed at Penn cost $1,700 and was particularly good at finding mutations that are only present in one of the two copies of a gene. Myriad’s test was somewhat different and cost $2,400. Once Myriad began enforcing its patent in 1999, women who wanted to be tested had only one recourse: Myriad. And as Myriad continued to enforce its patents, it also raised the price of its test so that it now costs $3,000 to $4,000.

The situation did not sit well with at-risk women, to say the least. Allison Gilbert is an author and mother. Her mother died of ovarian cancer at the age of 57, making her a prime candidate for the BRCA tests. Like Angelina Jolie, Gilbert tested positive for a BRCA mutation and decided to undergo a preventive double mastectomy. Not only is that a major life-altering decision to make on the word of a single company, but, in an opinion piece she wrote for The New York Times, Gilbert lamented, “While many insurance companies cover the expense for those at highest risk of breast and ovarian cancer, the tool is out of reach of many without coverage.”

Researchers weren’t happy either. Mary-Claire King, who first discovered BRCA1, noted in an interview with Slate that “genes had been patented before. … What was different about Myriad was its insistence that it was the only entity that could do the test, and its aggressive efforts to shut down anyone else.” Myriad did allow academic scientists to continue to study BRCA1 and 2, but they weren’t allowed to report test results to study participants, and that struck many researchers as ethically problematic.

Due to this perfect storm of circumstances, and the arrival of a science-focused lawyer at the ACLU, a group of plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against Myriad Genetics on May 12, 2009. The group, referred to in court documents as the Association for Molecular Pathology, et al., included 20 individuals and organizations: geneticists and other clinicians, professional societies, breast cancer advocates and patients. The first plaintiff to join the suit was Kazazian, who was eager to restore options to the thousands of people who had reason to suspect they might carry a BRCA mutation.

Here’s a quick synopsis of the case before it was heard by the Supreme Court:

March 2010: U.S. Federal District Court in New York rules that genes do not constitute patentable subject matter, so Myriad’s patents are invalid. Myriad appeals.

July 2011: U.S. Federal Circuit Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., overturns the District Court’s ruling. The plaintiffs (the Association for Molecular Pathology, et al.) appeal to the Supreme Court.

March 2012: The Supreme Court tells the Circuit Court to reconsider the case in light of a recent (Supreme Court) ruling regarding drug delivery methods and dosage testing.

August 2012: U.S. Federal Circuit Court hands down the same ruling as before. The plaintiffs appeal.

November 2012: U.S. Supreme Court agrees to hear the case.

Wanting to watch the proceedings, but not wanting to wait in line beginning in the wee hours of the night, Kazazian paid a line stander to wait for him outside the Supreme Court beginning at 4 a.m. on April 15, 2013. Kazazian relieved the line stander at 7 a.m. and was No. 49 of the 50 people that security allowed into the small, majestic court. Each side got 30 minutes to argue its case, with the judges asking pointed questions throughout.

Kazazian enjoyed the proceedings, especially the analogies made, like Sonya Sotomayor pointing out that you can patent chocolate chip cookies but you can’t patent flour, sugar or eggs. Aren’t genes naturally occurring substances, she asked?

On June 13, 2013, the Supreme Court handed down its decision, declaring that genes cannot be patented but cDNA, the “synthetic” DNA made as an intermediate step in some methods of gene testing, can be. While it was mostly viewed as a victory by patients and scientists alike, some have expressed doubts as to the scientific validity of the distinction made between the DNA of genes and the DNA of cDNA.

Hearing of the decision, Kazazian was “overjoyed.” “It was a real win for patients and researchers,” he says. “I don’t agree with their decision on cDNA because cDNA can be naturally occurring, too, but geneticists will probably be able to get around cDNA patents by offering genetic tests that use other methods.”

The bottom line is that there will probably be a lot of gene patents invalidated if they do not involve a specific methodology or a specific application or “use,” says Kazazian. But the specifics of each case will end up in the courts, so if you were ever considering a Ph.D./J.D., your job opportunities look good.

Gene patents and genetic testing in the United States (2007)

happyfaic72 on May 1st, 2020 at 15:52 UTC »

Don't read the excerpt below if you suffer from hypertension.

These pieces of shit

rogueIndy on May 1st, 2020 at 14:44 UTC »

People get all caught up in conspiracy theories and anti-science crap, but the real problems with with big pharma, big agra etc. are inevitably business practices like patent trolling and price hikes.

DrunkShroom on May 1st, 2020 at 14:34 UTC »

Patenting something someone else discovered. Wow.