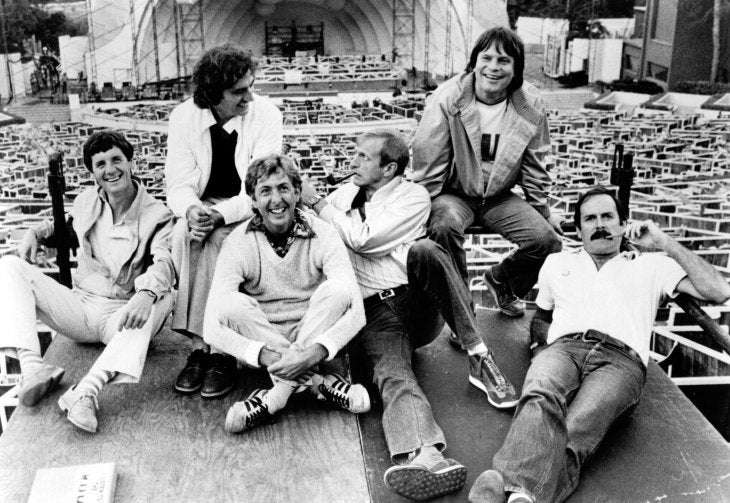

File: British comedy troupe Monty Python including (left to right) Michael Palin, Terry Jones, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, Terry Gilliam, and John Cleese, lounge about at the site of their filmed live show at the Hollywood Bowl, 1982. Chapman and Cleese smoke pipes. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

By Marialexa Kavanaugh with Jonathan Shifflett & John Horn

Eric Idle co-founded legendary sketch comedy group Monty Python. While writing and rewriting his new biography, Always Look on the Bright Side of Life, Idle realized the story he was telling was much larger than just him.

"You don't really know what part of your life is interesting," Idle said. "I discovered finally after three or four drafts that the book was actually about my generation, people growing up in our post-war England, rationing and poor. And that these kids who were born in the end of the war invented rock and roll."

Former Monty Python member Eric Idle has written a memoir (Courtesy of The Frame)

Monty Python is widely considered to have the same level of influence on the comedy world that the Beatles and the Rolling Stones did on rock. British rock and comedy had their own symbiotic relationship through the '60s and '70s — including financing Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

"I mean it was Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Genesis, Jethro Tull — they all pitched in money so we could make the film," Idle said.

Each group gave about 10,000 British pounds for its production.

"The good news about them was that they didn't want the money back," Idle said. "They don't care and they don't interfere. They don't say 'Oh no, there should be a scene over here with someone with another head.' They are the best backers."

That's not to say that the film didn't have its own problems, but they made the movie better.

"Sometimes when you're making good work, you don't have enough money. It's uncomfortable and difficult and muddy, like the Holy Grail," Idle said. "It will turn out to be very good in the end because we didn't have enough, so you're inventing all the time."

Idle eventually became good friends with late Beatle George Harrison.

"His friendship meant an enormous amount to me," Idle said. "I was going through a broken marriage at the time. He was very encouraging and friendly and supportive. We'd go to his house and play guitars."

Harrison was more than just emotionally supportive — he mortgaged his house to help finance Monty Python's Life of Brian, taking a chance on the comedy troupe before they'd become so iconic.

"I mean, imagine what he says to the wife in the morning. 'Hello love, I've just mortgaged the house, I'm going to put it on this film over here,'" Idle said.

"We tried to sell it here in America, and it was like selling 'Springtime for Hitler.' They looked at us with jaws open, 'you must be mad!'" Idle said. "It was actually The Producers. It was supposed to be a film so awful that it would never make money. It was a tax write-off. The trouble was it made money, so they had to change it immediately."

With The Meaning of Life, Monty Python had to go to a film studio.

"We were running out of rich rock stars," Idle said.

The most meta intersection of Idle's love for comedy and music was with 1978's The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash, a music mockumentary satirizing the Beatles. The fake group received support and laughter from real-life Beatle George Harrison, who even made a cameo.

"He very much encouraged me. He also showed me this film called The Long and Winding Road," Idle said.

That film was still in post-production — but it ended up hitting some roadblocks, with the footage not being seen until The Beatles Anthology came out decades later.

"They couldn't agree on how to release it since they all bickered towards the end and everybody looks bad," Idle said. "My film of The Rutles is a parody of a film that was never released."

Mocking cultural phenomena and large institutions was at the heart of Monty Python. Their parodies went on to influence sketch comedy for generations, while their creative genius also made a dent in the world of Broadway. Their religious comedy musical Spamalot, which won the Tony Award for Best Musical and broke ground in that genre, paved the way for future satirical hits like The Book of Mormon. They took their punk attitude to the making of that show.

"By and large nobody had the power to stop us doing what we wanted," Idle said. "Even from the beginning when the BBC washed their hands and said, 'Oh just do what you want.' When we made even Spamalot ... we wouldn't give them the script. So they said, 'Well what do you want?' I said, 'Well, the budget's 10.12 million, and here's a 12-line poem that I've written.'"

That poem included everything in the movie, and it got the project greenlit. Idle's whole career was the product of learning at an early age that being funny could serve as a survival tactic. Forced to enroll in the British boarding school system, he found that humor could be a powerful defense against bullying.

"I would learn to just let go and not censor what I was thinking. And people would just laugh," Idle said.

While he was always able to put his humor to use, not everything he did was a success — like the movie Yellowbeard. He had fun shooting it with the all-star cast featuring, as Idle puts it, "every single living and breathing comedian." He also had fun with his co-stars, who would make him laugh all day, but that comedy wasn't reflected on-screen.

"The film was always rubbish. The script was never good," Idle said. "Graham [Chapman] was great but he wasn't a very good writer. He was an alcoholic, and if you added him with Peter Cook and Bernard McKenna, three alcoholics wrote that film."

Despite all his success, he retreated from public life and moved to France.

"That's more me," Idle said. "Most of my life is spent in a little room writing or just reading or being quiet. It isn't a big show business life. At certain times we met very interesting people, and I write about them, but actually my favorite thing to do is get away completely and be in the country. To read, write, think, walk, and eat."

Through it all, Idle said that he feels that he and Monty Python went way farther than they ever expected.

"I think we would be completely amazed if after four weeks of working on the show, somebody said it would be on next year," Idle said. "I think the one thing we agreed on is that it would never work in America. Fifty years later it's still all over Netflix."

Editor's note: A version of this story was also on the radio. Listen to it here on KPCC's The Frame.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the chronology of Monty Python films — the Life of Brian was released after Monty Python and the Holy Grail. LAist regrets the error.

You made it! Congrats, you read the entire story, you gorgeous human. This story was made possible by generous people like you. Independent, local journalism costs $$$$$. And now that LAist is part of KPCC, we rely on that support. So if you aren't already, be one of us! Help us help you live your best life in Southern California. Donate now.

Moonschool on March 1st, 2020 at 00:17 UTC »

Wouldn't the money equivalent in 2020 be massively different too?

bloopickle on February 29th, 2020 at 23:42 UTC »

In one of Eric Idle’s albums, he mentioned that The Meaning of Life was the only film they did in Hollywood, and the only film they did not see a profit on.

martintinnnn on February 29th, 2020 at 22:51 UTC »

And Life of Brian by George Harrison. Monty Python got a lot of help from rock legends!