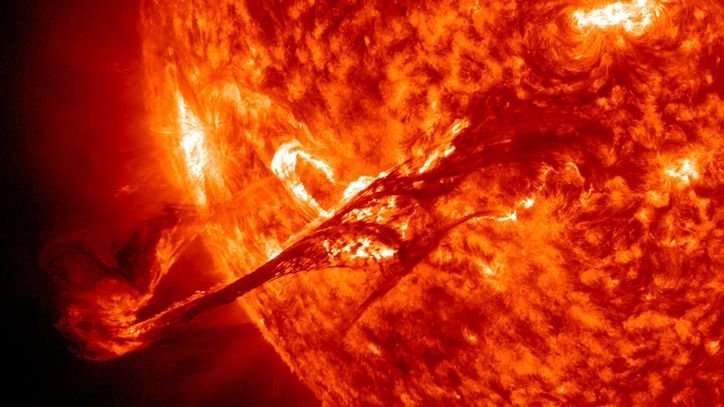

After a prolonged quiet period, the sun let off an explosion Wednesday when a new sunspot fired a small solar flare lasting over an hour.

The high-energy blast caused disruptions for some radio operators in Europe and Africa, but it was accompanied by a slower-moving, massive cloud of charged particles known as a coronal mass ejection (CME) that will deliver Earth a glancing blow this weekend.

All those particles colliding with Earth's magnetic field could turn up the range and the intensity of the aurora, also known as the northern and southern lights. Aurora are caused by particles from the sun that are constantly flowing toward our planet, but a CME delivers an extra large helping that can really amp up the display.

In North America, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that the aurora borealis could be visible as far south as New York and Chicago on Saturday, likely in the early morning hours.

One of the most helpful metaphors for understanding the difference between a solar flare and a CME comes from NASA, which uses the example of a firing cannon.

"The flare is like the muzzle flash, which can be seen anywhere in the vicinity. The CME is like the cannonball, propelled forward in a single, preferential direction."

As solar storms go, this one is relatively mild. Among the most extreme ever recorded is the 1859 Carrington Event, which is said to have created aurora visible almost worldwide and caused telegraph wires to burst into flames. Given our dramatically increased dependence on electromagnetically based communications today, the repeat of such an event could devastate a lot of our infrastructure.

This week's flare and CME are a potential indication that the sun is becoming a little more active after it spent the majority of 2018 and 2019 without a single visible sunspot on its surface.

Catfrogdog2 on March 22nd, 2019 at 07:06 UTC »

Will it also push the aurora australis further north?

Edit: after reading the article, the answer is Yes

begsthehessian on March 22nd, 2019 at 07:01 UTC »

Any chance of seeing it in Germany? Tonight maybe?

MiamiPower on March 22nd, 2019 at 05:37 UTC »

After a prolonged quiet period, the sun let off an explosion Wednesday when a new sunspot fired a small solar flare lasting over an hour.

The high-energy blast caused disruptions for some radio operators in Europe and Africa, but it was accompanied by a slower-moving, massive cloud of charged particles known as a coronal mass ejection (CME) that will deliver Earth a glancing blow this weekend.

All those particles colliding with Earth's magnetic field could turn up the range and the intensity of the aurora, also known as the northern and southern lights. Aurora are caused by particles from the sun that are constantly flowing toward our planet, but a CME delivers an extra large helping that can really amp up the display.

In North America, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that the aurora borealis could be visible as far south as New York and Chicago on Saturday, likely in the early morning hours.

One of the most helpful metaphors for understanding the difference between a solar flare and a CME comes from NASA, which uses the example of a firing cannon.

"The flare is like the muzzle flash, which can be seen anywhere in the vicinity. The CME is like the cannonball, propelled forward in a single, preferential direction."

As solar storms go, this one is relatively mild. Among the most extreme ever recorded is the 1859 Carrington Event, which is said to have created aurora visible almost worldwide and caused telegraph wires to burst into flames. Given our dramatically increased dependence on electromagnetically based communications today, the repeat of such an event could devastate a lot of our infrastructure.

This week's flare and CME are a potential indication that the sun is becoming a little more active after it spent the majority of 2018 and 2019 without a single visible sunspot on its surface.