Huh. Why, over five years, did Curiosity get only one birthday party?

To find out, I emailed Florence Tan, the deputy chief technologist at NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Tan was the electrical lead engineer for Curiosity’s sample-analysis unit, known as SAM.

“The answer to your question will sound rather cold and unfeeling,” her email began.

“In a nutshell, there is no scientific gain from the rover playing music or singing ‘Happy Birthday’ on Mars,” Tan said. In the battle between song and science, science always wins.

Tan acknowledged that this may be a difficult truth for some. “We earthlings,” as she put it, tend to anthropomorphize robots. Many studies have shown that people can have feelings of attachment and protectiveness toward robots as they would for humans. The more “alive” a robot appears, the more likely people are to react to it in ways usually reserved for living beings. In various scenarios, people have felt empathy for Roombas, dinosaur toys, and bomb-disposal robots. All three are nothing more than boxes of wires, circuits, and sensors, but they exhibit enough autonomy, enough signs of “aliveness,” to trigger emotional responses. Scientists and astronomy fans are currently slogging through a weeks-long public mourning period for the Cassini spacecraft, which will end its mission next month. One planetary scientist recently told me she feels like she should be sipping vodka the day Cassini burns up in Saturn’s atmosphere, in a somber tribute to a brave pioneer.

So it’s no surprise that the idea of a space robot “celebrating” its birthday—the very thing that makes something alive—makes people feel all the feels, even if they know it doesn’t make sense. As one user wrote back in 2013, “It’s literally an inanimate object why am I still crying.”

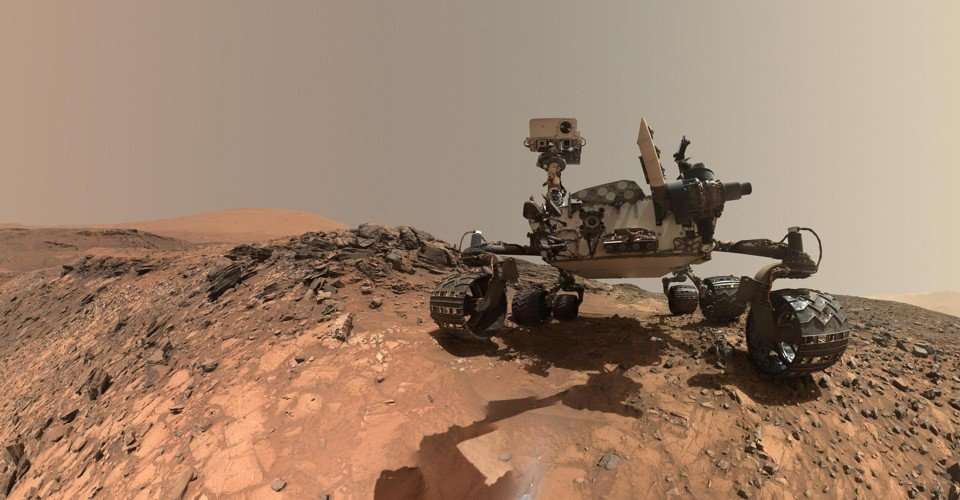

For Tan, Curiosity isn’t a cute robot, it’s a $2.5 billion national asset. Tan said she and other Curiosity team members are mindful of the purpose of the mission, which is to study Mars. The process of generating and transmitting commands to Curiosity takes weeks of preparation and involves reviews and walk-throughs with various groups. “It’s not just, ‘Oh, I’m ready to send a command, just send an email to somebody,’” Tan said in a phone interview. The rover’s activities are scheduled down to the minute, and SAM requires power to operate. Curiosity runs on a nuclear battery that turns heat into electricity, and it will eventually die.

Tan and Tom Nolan, her husband and fellow Curiosity engineer, came up with the idea of turning SAM’s vibrations into music in 2007 as they worked on the hardware. Nolan quickly built a program and got SAM to “sing” “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” In August 2013, as Curiosity’s first anniversary approached, Tan asked Paul Mahaffy, the lead scientist on SAM, if they could get Curiosity to sing “Happy Birthday.” The team tested the commands on an identical version of SAM that resides at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and then transmitted them to the real thing. The tune, which you can listen to here, sounds almost like the humming noises of the animated robot, WALL-E.

bobert3469 on August 5th, 2018 at 12:47 UTC »

Kind of weird to think that Mars is entiely populated by robots. If true A.I. comes to be, would robots think of them as their Columbus or Armstrong?

Dreamininacasket on August 5th, 2018 at 08:10 UTC »

WHY. HE DESERVES IT EVERY YEAR.

Hapouch on August 5th, 2018 at 07:52 UTC »

If you feel alone, think of him