How much is a child’s future success determined by innate intelligence? Economist James Heckman says it’s not what people think. He likes to ask educated non-scientists -- especially politicians and policy makers -- how much of the difference between people’s incomes can be tied to IQ. Most guess around 25 percent, even 50 percent, he says. But the data suggest a much smaller influence: about 1 or 2 percent.

So if IQ is only a minor factor in success, what is it that separates the low earners from the high ones? Or, as the saying goes: If you’re so smart, why aren’t you rich?

Science doesn’t have a definitive answer, although luck certainly plays a role. But another key factor is personality, according to a paper Heckman co-authored in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last month. He found financial success was correlated with conscientiousness, a personality trait marked by diligence, perseverance and self-discipline.

To reach that conclusion, he and colleagues examined four different data sets, which, between them, included IQ scores, standardized test results, grades and personality assessments for thousands of people in the U.K., the U.S. and the Netherlands. Some of the data sets followed people over decades, tracking not just income but criminal records, body mass index and self-reported life satisfaction.

The study found that grades and achievement-test results were markedly better predictors of adult success than raw IQ scores. That might seem surprising -- after all, don’t they all measure the same thing? Not quite. Grades reflect not just intelligence but also what Heckman calls “non-cognitive skills,” such as perseverance, good study habits and the ability to collaborate -- in other words, conscientiousness. To a lesser extent, the same is true of test scores. Personality counts.

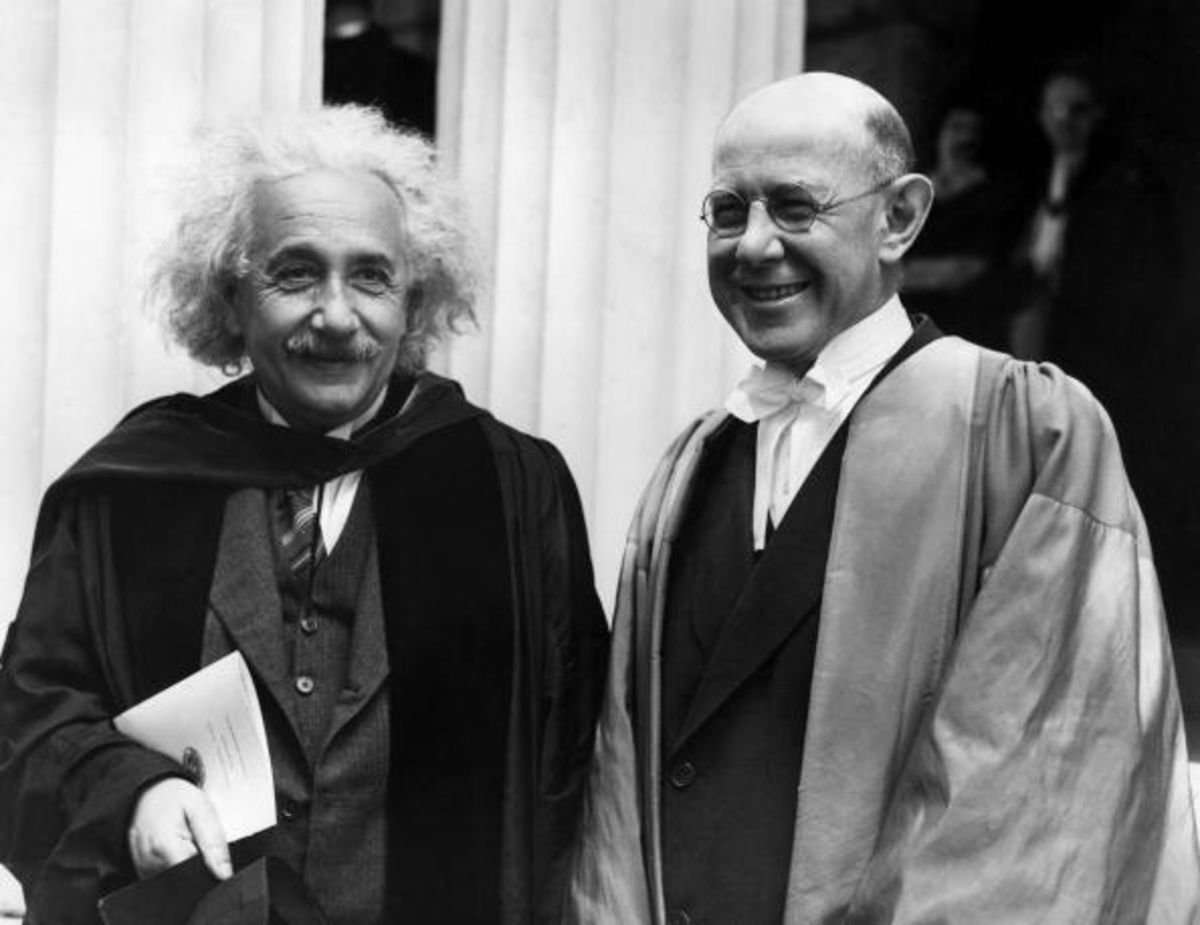

Heckman, who shared a Nobel Prize in 2000 and is founder of the University of Chicago’s Center for the Economics of Human Development, believes success hinges not just on innate ability but on skills that can be taught. His own research suggests childhood interventions can be helpful, and that conscientiousness is more malleable than IQ. Openness -- a broad trait that includes curiosity -- is also connected to test scores and grades.

IQ still matters, of course. Someone with an IQ of 70 isn’t going to be able to do things that are easy for a person with an IQ of 190. But Heckman says many people fail to break into the job market because they lack skills that aren’t measured on intelligence tests. They don’t understand how to behave with courtesy in job interviews. They may show up late or fail to dress properly. Or on the job, they make it obvious they’ll do no more than the minimum, if that.

John Eric Humphries, a co-author of the paper, says he hoped their work could help clarify the complicated, often misunderstood notion of ability. Even IQ tests, which were designed to assess innate problem-solving capabilities, appear to measure more than just smarts. In a 2011 study, University of Pennsylvania psychologist Angela Duckworth found that IQ scores also reflected test-takers’ motivation and effort. Diligent, motivated kids will work harder to answer tough questions than equally intelligent but lazier ones.

Teaching personality or character traits in school wouldn’t be easy. For one thing it’s not always clear whether more of a trait is always better. The higher the better for IQ, and perhaps for conscientiousness as well. But personality researchers have suggested the middle ground is best for other traits -- you don’t want to be so introverted that you can’t speak up, or so extroverted that you can’t shut up and listen.

What does any of this have to do with economics? “Our ultimate goal is to improve human well-being,” Heckman says, and a major determinant of well-being comes down to skills.

A newer study published this month in the journal Nature Human Behaviour focused on the flip side of success: hardship. After following some 1,000 New Zealanders for more than 30 years, researchers concluded that tests of language, behavioral skills and cognitive abilities taken when children were just three years old could predict who was most likely to need welfare, commit crimes, or become chronically ill.

The lead author of that paper, Duke University psychologist Terrie Moffitt, says she hopes the results would foster compassion and help, not stigma. Her results also suggested that helping people improve certain kinds of skills before they’re out of diapers would benefit everyone.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

RGTP_314 on May 1st, 2018 at 12:03 UTC »

Almost all of these studies confirm that IQ is one of the single best predictors of positive life outcomes. However, journalists (and sometimes the authors of the studies) frequently use a bit of semantic trickery to deceive people about the results. This study did not find that personality has a bigger influence on success, they found that personality is a unique predictor of success. All this means is that predictions are more accurate when you have IQ and personality together, rather than just one. It does not mean that personality alone accounts for more variance than IQ alone. These kinds of findings are sometimes worded in an intentionally deceptive way, such as "The effect of personality on success was observed above and beyond the effect of IQ".

The effect of intelligence on life outcomes in general gets stronger with age. The reason is thought to be due to the fact that the effects of having a higher IQ take time to accumulate. Thus, almost all relationships between IQ and some outcome are weakest when using a younger population, which is usually the case when you have GPA data. The linked study seems to use a mix of older and younger participants, but the authors are not clear about the ages in which each variable was measured. However, the fact that they have GPA suggests that measurements were taken in childhood/adolescence.

In any case, the important take-away is that the actual results of the linked study are consistent with what we've known for years (meta-analysis 1, meta-analysis 2): IQ is consistently the single best predictor of success. You can improve predictions by measuring more variables, but if you can only measure one variable, IQ is what you want to know.

Reverent on May 1st, 2018 at 11:10 UTC »

As a person who has worked in technical sales for multiple years (an unholy frankenstein between support and pre-sales), yeah, sales is literally your facebook friend value.

Senior sales makes ridiculous money, and they earn it. It isn't because they have a super aggressive, super winning sales attitude, it's because they know people. They remember faces, they remember names, and this accrues actual value over time. At a certain stage, you become less valuable for your skills, and more valuable for your virtual roledex you store inside your head.

I've literally seen people hired because they have connections with educational people, consultant people, etc. If you can store faces, store names, and keep a healthy relationship with them, you become a roving gold mine. Every company you join can mine you for dollars for days.

If you want to become successful, become good at maintaining relationships. There's super good value in it. If you're face-blind (like me), you better be really good at something else.

prince_harming on May 1st, 2018 at 10:35 UTC »

This is increasingly the case as knowledge becomes more specialized and collaboration becomes more important, as in our modern world.

If you are charming but not particularly intelligent, you can get intelligent people to work with/for you, you can coordinate their efforts, and you can manage them effectively.

If you are intelligent but not particularly charming, the opposite is harder to accomplish. It can still happen, with Zuckerberg being a recent prominent example, but it is rarer. People don't want to work when they're treated poorly, especially when their talents are in demand elsewhere.

People skills are required for good leadership. They instill confidence, they gain trust and support, they let you get away with more mistakes. Good leadership leads to effective teamwork, and effective teamwork leads to success. The way things are now, the person who coordinated all of that work tends to get the credit, as the lynchpin of the organization.