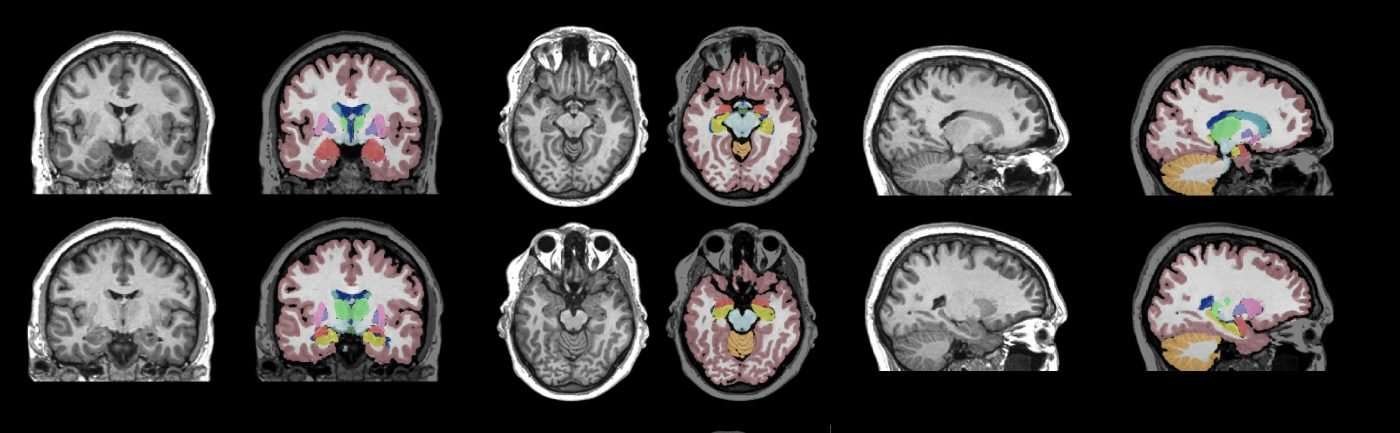

A newly released study is the first to show that healthy older people continue to produce new brain cells. Researchers autopsied 28 healthy brains donated by people who had no neuropsychiatric disease or treatment affecting the brain. The fact that neurogenesis – the process by which neurons or nerve cells are generated in the brain – continues as people get older means researchers are better equipped to understand why things can go wrong as we age, like with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease.We spoke to lead author Maura Boldrini , associate professor of neurobiology at Columbia University, about the work.We were interested in understanding if neurogenesis persists in people who are aging, have no disease affecting the brain, and no cognitive impairment. No previous study has looked at neurogenesis in humans who had no neuropsychiatric disease or treatment at time of death, and studies in mice showed that neurogenesis declines after middle age. Humans have much more complex learning abilities and emotional responses than rodents, both of which may depend on neurogenesis. A smaller hippocampus with aging was also hypothesized based on in vivo imaging studies.We found that neurogenesis does not decline with aging, nor does the volume of the dentate gyrus, part of the hippocampus thought to contribute to the formation of new episodic memories. Instead, it’s the formation of blood vessels that seems to decline with aging. Some forms of plasticity might be blunted as well, as the number of cells expressing the plasticity marker PSA-NACAM decline. This may mean that these neurons could be making fewer connections and are less active in the circuit.New neurons in the hippocampus are necessary for memory and emotional responses to stress. Our brain keeps making new neurons throughout our lifespan, and this is unique to humans. These neurons might be important for humans to transmit complex information to future generations, and to sustain our emotionally guided behavior, as well as integrating complex memories and information.Previous negative studies have come as a result of a few factors. One is the availability of only portions of the hippocampus, so the total number of cells could not be calculated. Studying tissue fixed with different chemicals can affect the ability to see the cells we are interested in, and long postmortem intervals affect protein quality. Furthermore, not knowing the subjects’ disease and treatment history, which affect neurogenesis, can make it difficult to evaluate results. There were many confounders that can all affect neurogenesis per se, or the ability to see it.This means that with a healthy lifestyle, enriched environment, social interactions, and exercise, we can keep these neurons healthy and functioning and sustain healthy aging. We can also study what goes wrong when people experience memory loss, dementia or emotional problems. We hope to find new treatments that can sustain these neurons and the vascularization of the brain and cure these conditions.We are interested in understanding how neuron proliferation, maturation, and survival are regulated by trophic factors, transcription factors, hormones, and other molecules. This could help us find treatments for cognitive impairment or dementia. We are also interested in comparing these findings obtained in healthy aging individuals with people with cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s, or vascular dementia.Featured image courtesy of Tracy Abildskov

Aging people grow just as many new brain cells as young people

Y-27632 on April 5th, 2018 at 17:16 UTC »

That is a terrible title that significantly misrepresents the contents of the study.

It's more like:

"A small, specific region of the brain (but very important because it's heavily involved in memory formation) contains just as many neural progenitor cells of a certain type in old people and in young people. However, there are still notable differences in that area of the brain in old people, like a reduced population of stem cells that give rise to these neural progenitors, lowered ability by neurons to form and remodel connections, and reduced growth of new blood vessels."

Edit: Apparently some people are getting triggered, so let me say that this is meant to be a clarification of the basic facts, not an alternate title suggestion. Nobody sane uses paragraph-length titles.

zinfandelightful on April 5th, 2018 at 17:06 UTC »

Notable that the neurogenesis observed here was in the dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus (memory central), not all over the brain.

Also, how to reconcile this study with this finding reported just about a month ago?

CaptnCarl85 on April 5th, 2018 at 16:43 UTC »